Our Drought and the Dutch Idea

By Julian Warmington

Wheeling the bike onto the Mugunghwa carriage, I lock it to a pole and take a seat. I want to watch the beautiful Korean countryside slide by. The train jolts to a start and the city soon slides into open, lush, green countryside. I relax and am happy – for a brief while – at the thought of returning to the even more beautiful southwest corner of the peninsula.

But as the train glides south, a frightful vision rises out of rice fields. Like a scary movie monster threatening an attractive film star, all over the previously pristine Korean countryside is a rapidly rising slew of milking factories and dairy cow sheds.

Now, these days, I am fearful about the state of the drought emergency in Jeollanam-do, but since that train ride just two years ago, the development of this drought has not been surprising at all, and this is why: I have already seen this awful environmental own-goal happen before elsewhere, twice.

The meager good news is that there are a couple of easy and very affordable things we can all do today – and every day – to make an immediate, meaningful, and lasting difference in a shared effort to avoid more such awful situations as this dry spell.

How stressful was it/has it been for you? What did you do, or have you done to help reduce the impact of water scarcity on yourself and others? How are you helping to share the effort of preserving what little is left and avoid future droughts? Was your apartment’s water pressure reduced, or have you put a brick or something else bulky in your toilet’s water cistern?

These are valid, creative ideas for reducing individual impact on a small scale, and Chung Hyunhwa was right to offer them as ideas here in the Environment column within the Gwangju News (issue #251). Our good editor, William Urbanski, also offered useful personal reflection on real lived experience and the perils of industrial-strength overcrowding via carbon-intensive concrete jungle apartment blocks on the local water table and our collective psyche alike (also issue #251).

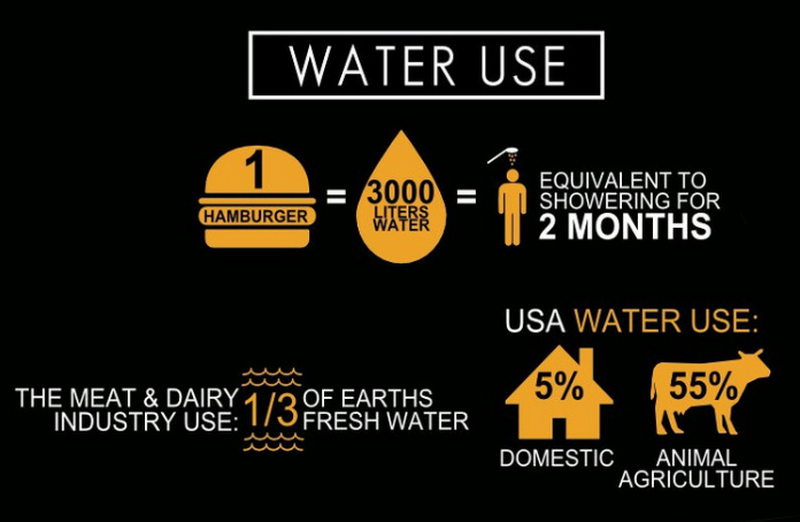

We are, however, missing an important part of the story of water demand, depletion, and degradation, as it affects this and future water shortages. The film Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret was released and added to the documentaries available on Netflix in 2014. One of the best things about this film is its use of infographics clearly explaining the environmental damage created by industrial animal agriculture.

One of the most disturbing sections of the movie focuses on the use and abuse of water by beef and dairy farms. Filmed in California before 2013, it precedes the current state of ongoing severe drought throughout the central and western USA. But already a wide range of other major environmental issues had been resulting directly from beef and dairy farms, including local health impacts on humans, and oceanic “dead zones,” vast offshore areas where farm pollution is so thick that all other life forms die.

The year Cowspiracy was released, Oxford University scholar Professor Joseph Poore started a new study. Like all good scientists, he and his research team were skeptical and set out to disprove the film. In 2018, news of their five-year-long study was published in the prestigious peer-reviewed journal Science. Reputable paper The Guardian reported their study with the headline “Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth.” Two of the areas studied were freshwater use and water pollution.

Since the day I first watched Cowspiracy, I had been waiting for someone to make a similar film on the mess dairy farms are making of the land and waterways where I was born: Aotearoa (New Zealand). The severe situations in the two countries are remarkably similar in many ways, including the awful impacts of dairy farm pollution on freshwater supplies.

The documentary Milked was released in 2021. While focusing on the impacts of the dirty dairy industry, it takes a balanced, nuanced, even supportive approach to New Zealand’s dairy farmers. Freshwater ecologist Professor Michael Joy speaks about how most native species of fish and other indigenous wildlife are now endangered and threatened with extinction as a direct result of all the poohs and wees from too many cows on too many fields on too many dairy farms all around the main islands of the country; however, he takes a positive approach to farmers. Dr. Joy suggests the government support dairy farmers with financial subsidies to help them transition out of animal agriculture as soon as possible.

I have a similar sense of sympathy for folks who are still quite literally addicted to the taste of cheese: Milk contains casomorphins, much like morphine, and makes us physically want to eat more. A cow’s calf is larger, grows more quickly, and is much more mobile than a human baby, so its mother’s milk has a larger, stronger dose of casomorphins to make the calf want to stay close to the safety of her side. When we take that milk and concentrate it into cheese, it intensifies the high that makes us want to return to the same cheese box in our fridge or pizza restaurant nearby.

But it is very possible to choose to change – and to stay changed – in our daily eating habits, as most of us know from our own experiences of changing our daily diet decisions, whether out of choice or availability. Local Koreans may have enjoyed foods from other cultures sometimes. Those of us who were born elsewhere and now live in Jeolla-do perhaps eat differently to when we were growing up, maybe including more spicy and salty foods for breakfast.

Long before I moved to Gwangju, I chose to stop eating meat and animal fat-based cheese, but perhaps up to about six months after I made that decision, I very occasionally still craved only pepperoni pizzas from a favorite downtown cafe. Those feelings soon faded, and my taste and health improved. Also, now, proven nutritional science to support what we already know about how we can consciously choose to change our taste buds has emerged.

Medical researcher Dr. Will Bulsiewicz is a USA board-certified gastroenterologist and author who highlights the influence of the microbiome, or stomach bacteria, to affect not only how we feel, but how we think about what foods we want to eat next. Simply put, the more we eat of any food, the more bacteria we create to deal with it, and the more those bacteria demand even more of that food: The more sloppy, slimy pizza we eat, the more we will want it; or the more avocado salads we eat, the more we will crave that crisp, crunchy, fresh lettuce and rich, oily avocado instead.

But what else makes us continue to desire the animal fat-based foods that create so much damage to our waistlines and our home? In a single word: advertising. It is not only from the ongoing influence of family, friends, and colleagues that we give ourselves permission to continue in an unhealthy habit. We also get a face-full of reinforcement from media marketing all around us every day: photos of fatty, cooked meat in subway stations and bus stops; radio ads suggesting slurping more milk or scoffing more cheese; magazines and newspapers promoting meat-and-cheese-based restaurants; cafes where the only green tea option is a cow’s milk-based latte! Once we notice all the advertising and narrow range of options focused on animal fat-based foods all around us, it really is difficult to avoid the feeling that an idea is being shoved down our throats, invading our senses of imagination and identity alike.

Why do we do this to ourselves and others? Why do we permit our national broadcasting standards agencies to accept advertising of animal fat-based foods despite their impact on lives in and outside farms, including our own? Cancer is out-of-control cell growth often caused by the cow’s milk-based hormone IGF1; diabetes, obesity, erectile dysfunction, stroke, dementia, and other diseases are all similar blockages from eating too much saturated fat and the cholesterol only found in animal fat-based foods.

Last year, the Dutch city of Haarlem chose to end the advertising of meat products in bus shelters and on screens in public places. Adverts promoting consumption of animal milk-based “foods” will still be possible when the ban comes into effect in 2024, and meat will still be able to be advertised in newspapers and other public media.

This leaves room for Gwangju to be the first city to create a ban fully aligned with science, logic, and the danger of more drought: Gwangju could see an end to advertising for animal fat-based products including both dairy and meat, in public spaces and locally produced media.

This will happen when we do two simple things to help reduce the impacts of droughts: end eating and drinking all animal fat-based foods; and, much more importantly, simply talk. Insist on serious conversations with family, friends, colleagues, and especially local leaders at all levels: Demand to discuss the value of ending the advertising of animal fat-based foods.

The Author

Julian Warmington taught for twenty years at the university level in South Korea, half of which he spent in Gwangju. He established and ran the Busan Climate Action Film Festival and has given presentations internationally on teaching environmental issues within ESL lessons and curricula. His favorite Korean foods include vegan hotteok, vegan patbingsu, and vegan dolsot bibimbap.