The Gwangju Printing Village Is Dying

Written and photographed by Madeline Miller.

Walking through Gwangju on my albeit irregular commute through downtown, I have always been so curious about the familiar sounds and smells that seem to be coming from unfamiliar places. Just a few short steps away from the Asia Culture Center, on street after street you can hear the “clack-clack-clack” of offset1 presses running in the early morning. After poking about in places I probably did not belong, I was invited to spend the afternoon with a few experts in their field, known as pressmen.

For those of you who may not know, the print industry is the backbone of almost everything you can see. From the labels on your fast food wrappers, to calendars you get and throw away at the start of every school year, to the instruction manuals you definitely do not read in the boxes of medicine handed to you in every pharmacy – we could not live in today’s world without print.

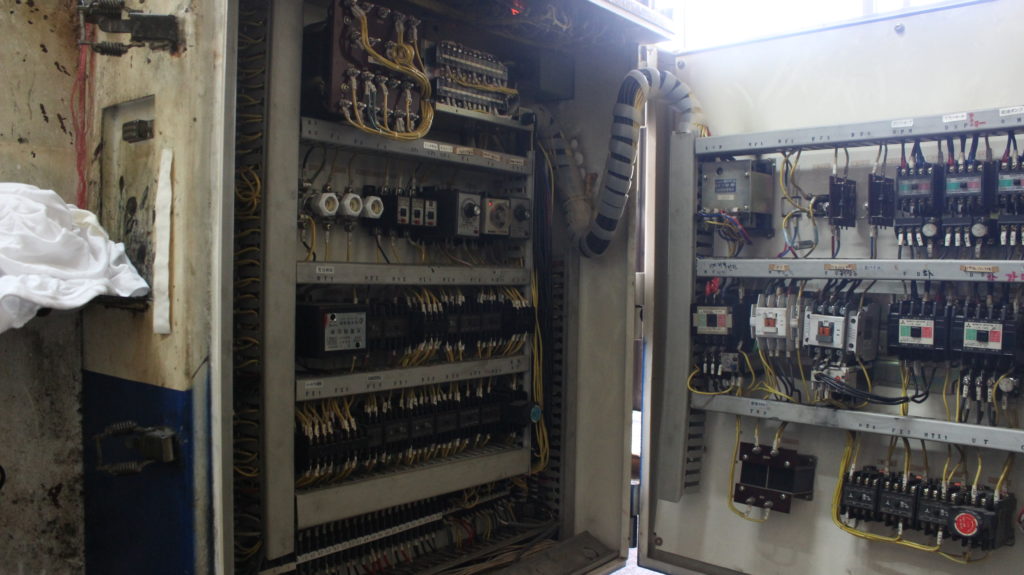

The main controls of a Litherone four-color offset press.It should come as no surprise that Korea, too, relies heavily on its printing industry to function. But, to my surprise, Gwangju has a whole separate living entity in its “Printing Village.” Coming from a background of printers, with perhaps even a little ink in my blood, I always understood that it was better for your business to be a ways removed from your competition. So, cue the shock when I came to learn that Gwangju print shops actually intentionally gather together.

My first afternoon quickly turned into several days spent with three small business owners in Dong-gu. Each laughed as they explained that, of course, Korean and Californian printing are quite different, but my shock still came as no surprise to them. The local culture dictates a give-and-take that hearkens to Confucian ideals of community. It is best in the industry here to be a specialist – the specialist, if you can – for a specific machine or process, and rely on others around you to be experts of their specialty, machine, or process, to fill in your gaps. U.S. printing generally is a “one-stop shop” in which the company tries to fill as many steps of the process as possible, rather than selling a job to someone else, which puts the business in danger of losing some of the profit, as well as running the risk of making mistakes down the line you as the primary seller cannot control.

The first step is to come up with a proof. This is the “ideal” for the finished product, like a template. This often includes a design phase, choosing colors, images, and text. Then the customers should request any changes they want to see by doing markups. Sometimes this is an incredibly quick process that involves using a computer wordprocessor, typing out some text, and printing immediately. Sometimes it takes some back-and-forth between the printer and the customer.

The next step is the actual printing. If it is on a digital press, it does not take too much make-ready, but on a traditional press, this can take a lot of practice runs to make sure the alignment, colors, and air flow are just right. Usually there is a certain percent of “overs” – if the customer orders 1,000 pieces, the printer will plan to make 1,200 pieces to allow for trial and error in the various stages of printing.

After printing, sometimes the size of the product should be adjusted by cutting. The cutter’s job is exactly what it sounds like. Sometimes this just means cutting separate pages of a book apart, or perhaps creating an irregular shape for the finished product.

Next may come binding, which has a wide variety of components. If pages need to be stapled together, or if there are some kind of stamps, die-cuts, or other decorative processes for the product after printing, it is done in the bindery.

Lastly comes shipping and handling – this could include grouping and banding finished pieces together, packaging, and labeling. Gwangju’s Printing Village and my parents’ company differ the most in this area. The Printing Village shops deliver the finished product directly every time, so they do not typically need additional packaging. My parents’ company, though, often relies on shipping companies, in addition to the company’s drivers, because of how far each customer is from the shop. Gwangju print shops are typically close to the customer and thus hand-deliver.

The major difference between the Printing Village and my experience in the U.S. print industry is that you have to turn over the job to someone else at each step of the process, but, somehow, that does not seem to interrupt the communication flow. As long as the proof is delivered to the next shop, too, there is less chance than I had expected of error or a dissatisfied customer.

This co- and inter-dependence of experts in their tiny single-room factories led to the emergence of the Printing Village. The majority of the jobs in the 1970s and 1980s were centered around the Old Provincial Office because of the number of commissions relating to government materials. I was at first confused: Delivery seems to be fairly straightforward; what advantage was there to being so close? Could you not just send a truck with the finished job to the customer? My pressmen let me in on a little secret: Back in the day, he was a messenger, and in the winters running proofs back and forth between the Old Provincial Office and the shop was bad enough even in close proximity. Then, additionally, carrying the plates, proofs, or ink all the way across town, as a single-machine shop counting on another single-machine shop to finish a commission, would only compound the issue. In order to work together with other shops, and for the Old Provincial Office during the winter, print shops needed to be as close as cabin fever would allow.

As is to be expected, the industry has faced many changes over the years. One of the major sources of work for Korean presses was textbooks and notepaper for schools and universities. As course materials have been sourced more and more from big publishing companies and office suppliers have taken over the notepaper market, our little print shops have had to focus more and more on the government jobs.

Because of the advance of digital presses and laser printing, the whole process of proof-to-print is something you can see in a quick trip to the local copy shop – they may even have a tiny bindery where you can pay 10,000–20,000 won for a copy of a textbook and watch them do the whole thing. Granted, the quality is a little less than the original, but it is cheap and takes less than a couple hours. In fact, this is largely what is bringing about the slow death of the Printing Village. The pressmen told me that because the customer now cares more and more about speed than about quality (and perhaps cannot even see much of a quality difference), the “real” presses are becoming less valuable, and people are turning more and more to a copy shop to do that kind of work.

While the Korean population is fond of sticky notes, labels, and other adhesive products that are also run through a press, the majority of these types of jobs, too, have been claimed by a much bigger company, mainly because they require several types of special equipment that most general printers would not traditionally be trained on or have the capital to buy in the first place.

Cutters especially seem to have less work now than before. As there are more and more customers preferring digital print, products are coming in pre-cut sizes. A4 is satisfactory for anyone walking into a copy shop, and most people can use a hand cutter for a small quantity. Things like calendars, large envelopes, and 500-page manuals for in-house training are still printed regularly but are anticipated to phase out in the near future. Fliers for tourism, like the 2019 FINA swimming competition’s commission for maps, are keeping a work flow, but when asked about the future of the Printing Village and the industry at large, all three of my hosts told me spryly that they are the last of their kind but also do not plan to retire anytime soon.

A special thanks to:

Cheon Hong-gi (천흥기) at Cheon-il Printing (천일인쇄)

Cheh Chun-shik (최춘식) at Seong-eun Cultural Printing (성은문화사)

Pak Heong-ohk (박형옥) at Aju Printing (아주인쇄)

Footnote

1 In offset printing, the design is transferred from the design plate made of thin metal, somewhat like a stencil, to a rubber blanket that mirrors the design, to the target substrate (typically paper or cardboard). It has been in use since 1875.

The Author

After living in Gwangju for four years and having studied Korean, Maddy Miller has a unique opportunity to find areas of particular interest that others may not have access to because of the language barrier. Luckily, the pressmen were nice to her; she can be a little pushy sometimes. A love of real books prompts her to do her part to keep the printing industry alive.