Descendants of the March 1st Movement: Generation MZ with Light Sticks – March 2025

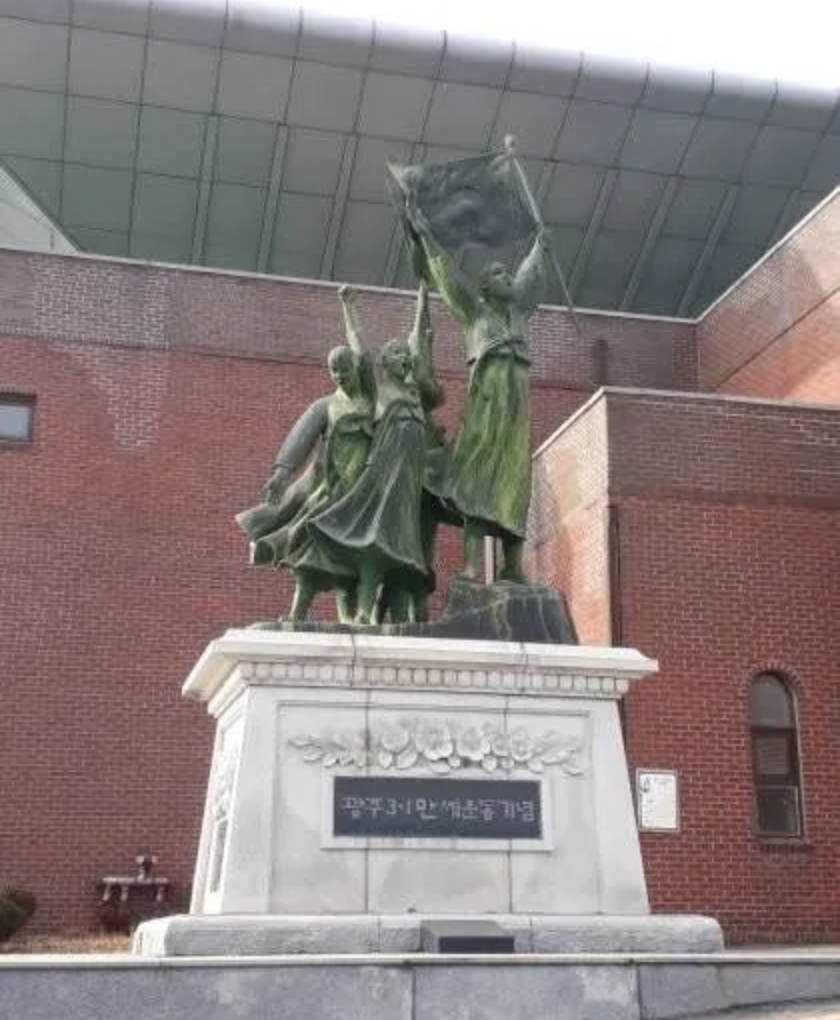

“Can the past help the present?” and “Can the dead save the living?” These questions, central to Han Kang’s exploration of the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, resonate deeply in modern South Korea. Over 500 people were killed by martial law forces in Gwangju in the May 18th Uprising of 1980, just as more than 7,000 were killed in the March 1st Movement of 1919. These historical atrocities serve as stark reminders that remembering and confronting past suffering is essential for healing and preventing future injustices.

These reflections have resurfaced amid South Korea’s current political turmoil following the December 3 martial law decree – a palace coup by a president yet to be impeached. The historical memory of the March 1st Movement and the Gwangju Uprising provided today’s citizens with the courage to quickly nullify the late-night imposition of martial law. The sacrifices of those who fought and died in 1919 and 1980 paved the way for modern-day protesters who physically faced martial law troops but survived in front of the National Assembly.

Generation MZ and the Evolution of Protest

Historically, youth have led Korea’s resistance movements. Today’s MZ Generation (that is, Millennials [born between 1981 and 1996] and GenerationZ(bornbetween1997and2012])shares this legacy but distinguishes itself in key ways.

Having witnessed government failures during the recent Park government and the current Yoon administration, including the Sewol ferry disaster and the Itaewon crowd-crush tragedy, the MZ Generation is deeply skeptical of authoritarian leadership. Unlike the older 386 Generation (born in the 1960s), who faced ideological suppression and relied on traditional protest methods, the MZ Generation leverages digital tools and decentralized communication to mobilize quickly and effectively.

Characteristics of the MZ Generation

The MZ Generation prioritizes economic rights and leisure, and rejects traditional gender roles and marriage norms. They value diversity and inclusivity, integrating the internet into daily life and preferring digital interactions over face-to-face communication. Their consumer habits are shaped by online reviews, influencer marketing, and fast, efficient delivery services.

Beyond consumerism, they actively engage in social movements. Their fandom culture extends beyond supporting idols to promoting activism, as seen in BTS’s UN address advocating youth participation and Blackpink’s climate advocacy.

Expression of the MZ Generation

Unlike past protests requiring physical presence and ideological commitment, MZ activists use digital platforms to live-stream demonstrations, coordinate efforts, and provide indirect support through prepaid purchases of food and supplies. Their activism extends globally, engaging overseas Koreans and international supporters.

A defining feature of their protests is the use of K-pop light sticks, transforming them into symbols of non-violent resistance. Humor, memes, and digital creativity have further broadened participation, making activism more inclusive and dynamic.

MZ activists also demonstrated solidarity with farmers who were attempting to join the protests, using social media to highlight their struggles against police roadblocks. In freezing temperatures, they arranged heated buses and food deliveries through quick-service apps, demonstrating their commitment in innovative ways.

Theoretical and Political Implications

Terror management theory (TMT) suggests that existential threats push people to reinforce cultural values and seek symbolic immortality. Generation MZ’s activism reflects this, as they respond to national crises by asserting their collective power through digital and physical actions.

Historical Context and Conclusion

South Korea has a rich history of youth-led uprisings, from the 1894 Donghak Peasant Revolution to the 1919 March 1st Movement, the 1960 April 19 Revolution, the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, the 1987 June Uprising, and the recent 2016 Candlelight Protest. The 2024 protests share their commitment to non-violent resistance and civic responsibility.

International media have highlighted South Korea’s unique protest culture, where demonstrators not only resist injustice but also clean up after their protests, reinforcing their civic-mindedness. The MZ Generation has shown that activism can be innovative, inclusive, and deeply impactful.

As this generation emerges as a dominant political and economic force, leaders must recognize and integrate their values. Future leadership will require more than charisma – it will demand engagement with a digitally connected, politically aware generation shaping a new era in South Korean democracy following the tradition of the March 1st Independence Movement and the May 18 Democratization Movement.

In Appreciation

Choi Chong-Myoung contributed the original text for this article. With a doctoral degree in counseling psychology, she is the director of the Gwangju Mudeung Branch of HugMom Hug-In. She is also a researcher at Chonnam National University’s Institute for Democracy and Community Studies.

Article translation and adaptation by Dr. Shin Gyonggu.

Photograph courtesy of Hong Inhwa.