Jeolla and the Nosa School: Combatting Western Influence

We often think of Korea’s neo-Confucianism of Joseon Dynasty times as a singular concept, but in actuality, it was more of an umbrella term for the differing schools of thought that existed simultaneously as well as those that developed sequentially during Joseon times. One of these schools of neo-Confucian thought was that of the Nosa School, developed in the Jeolla area by Ki Jeong-jin. Its tenets proved to have a profound influence on late Joseon Dynasty government policy. Resurrected here from the archives of the Gwangju News is a two-part contribution by Hea Ran Won, “The Nosa School and Western Influence” (January 2016) and “The Nosa School and the Opposition Against Western Influences” (February 2016). We hope you enjoy this article on the Nosa School, a part of history that arguably hasn’t received the degree of attention that it deserves. — Ed.

Early Western Influence on Korea

Unlike China and Japan, Korea was long hidden from the eyes of the West due to its geographical seclusion. It was only from the middle of the 19th century that the West actually started to take an interest in Korea. However, the relationship between Korea and European countries was not a friendly one. In fact, their relationship was like that of water and oil. The European countries were filled with imperial aspirations, while Korea’s Joseon government was heavily prohibitive of Western culture.

In the mid-19th century, European countries started to send more ships to the Korean coast. Officially, these ships claimed to be exploring the marine ecology, but in reality, they were measuring and investigating the shorelines and coastal regions of Korea in preparation for intrusions of various sorts. In the case of Jeolla Province, the English battleship Samarang unlawfully entered Jeolla waters and monitored several islands near Goheung and Jangheung on the south coast, and a Russian battleship twice invaded Geomun-do (an island near Yeosu). The locals feared these ships because they would often force trade and even plunder villages. In addition, Koreans became more anxious after hearing the news of attacks on Beijing by British and French forces. It was shocking to hear that these Western forces easily seized the capital of a big and powerful country like China.

In response, the government of Joseon banned Christianity, which was viewed as the key connection to European countries. Despite severe oppression, however, the number of believers in Korea grew, and the government became wary of its influence. It was feared that Christianity would disrupt the traditional Confucian mindset, and to prevent the further spread of Christianity, the government publicly executed thousands of Christians.

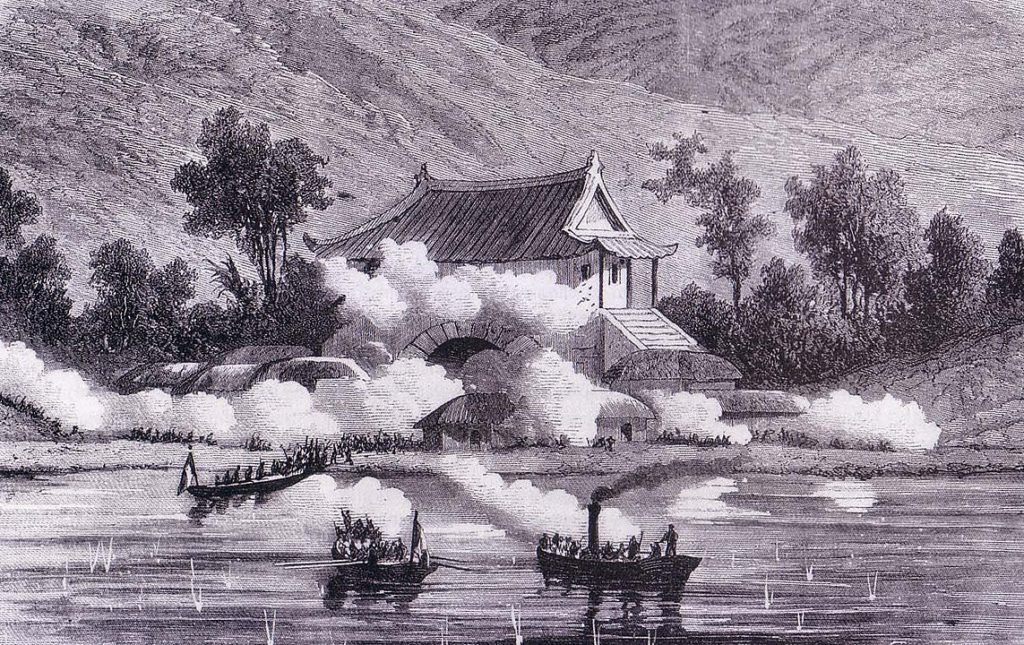

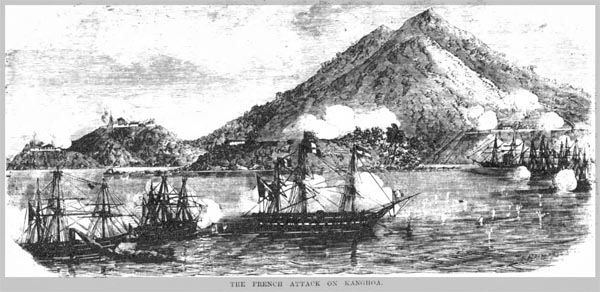

European countries saw this oppression as an opportunity to invade Korea. In 1866, Father Felix Clair Ridel, who fled Korea for fear of persecution, informed French Admiral Pierre Roze in Beijing of the massacre of Christians that was happening in Korea. The French admiral decided to attack Korea and even notified the Chinese government not to take any action regarding the planned offensive. The assault by the French fleet lasted three months. Korea managed to secure its capital, but the French plundered Ganghwa Island to the west of Seoul and took away much of its weaponry and many books.

This incident further aggravated the relationship between Korea and the West. Originally, Korea was divided into two camps: those who claimed that they should accept Western culture and embrace its advanced technology and weaponry, and those who wanted to prohibit any Western influence. The constant irritation and plundering of the Jeolla coastline and the French campaign against Korea in 1866 caused the government to side more with those who wanted to prohibit Western influences. This initiated the rise of the Nosa School, which greatly influenced Korean diplomacy for years to come.

The Influence of the Nosa School

Joseon Korea had ostracized other ideologies since the beginning of the dynasty (1398–1905). Joseon’s politics and social structure were largely based on neo-Confucianism, which criticized other beliefs and religions. Following this logic, Joseon ostracized Buddhism and Taoism, and used neo-Confucianism to maintain and strengthen the authority of the ruling class. In the late 1800s, these beliefs were emphasized due to the advancement of Christianity, which was challenging the traditional values and, along with people’s distrust of European explorers and imperialists, were contributing factors that led to the birth of the Nosa School (노사학파, Nosa-hakpa).

The Nosa School followed the logic of neo-Confucianism. Ki Jeong-jin (기정진, 1798–1879) was the founder of the Nosa School and was a well-known neo-Confucian scholar. He was born in Sunchang (North Jeolla Province), and later worked actively just south of there in Jangseong (South Jeolla Province). In his 40s, he published a series of writings that emphasized the function of Yi, the Nosa Collection (노사집, Nosa-jip; Ki’s scholarly moniker was “Nosa”). He believed that Yi (理), which was the reasoning of heaven, provided all of creation and that every creation had its own place. Therefore, he saw incidents such as a wife taking her husband’s place, a subject taking his sovereign’s place, or barbarians taking China’s place as causes of the greatest troubles of the world. His writings fascinated many neo-Confucian scholars to the extent that he gathered as many as 600 students who studied his thought. This was the beginning of the Nosa School in the early 1840s.

In politics, Ki Jeong-jin mainly argued for centralization of the government and Korean solidarity. He claimed that in order to correct the cultural disorder and defend the country against imperialism, a strong monarch should rule the country. Further, he argued that this strong monarch should care for his citizens as a governess cares for her charges and demanded the fast implementation of reforms that would benefit farmers.

However, he also formulated some radical concepts such as the “human–beast theory,” which compared the West and Christians to barbarians or beasts. He argued that only those holding neo-Confucian beliefs were human and that communicating with the West would turn such neo-Confucianists into barbarians, as well. Ki Jeong-jin’s argumentation was supported by Heungseon Daewongun, who was the father of King Gojong and the center of Korean power at the time, and because of this, Korea became much more defensive and skeptical of Western influences.

The effectiveness of the Nosa School’s policies is debatable. While the Nosa School contributed to the preservation of Korean culture and the growth of nationalism, it showed clear limitations in widening global insights. The Nosa School’s beliefs deepened conflict with Western imperial powers and formulated brutal policies that killed thousands of Christians in Korea. However, it was also the Nosa School’s beliefs that became the basis of struggles against invasion. Arising from the thought of Ki Jeong-jin in the Jeolla area, the Nosa School spread to form the Joseon government’s strong nationalism and inspire the militias of commoners who fought against coastal intrusions by Western forces in latter 19th century Korea.

Arranged by David Shaffer.