The Cruelty of Spring: Looking Back at the April 19 Student Protests in Seoul

Written by Wilson Melbostad

Photographs courtesy of the 4.19 Revolution Documentary Heritage to the UNESCO Memory of the World

Most of those residing in Gwangju know that with the onset of every spring comes discussion of the pain and horror suffered throughout the city during the May 18 Gwangju Uprising of 1980. Just muttering the number sequence o-il-pal (five-one-eight, 5.18) immediately indicates that one is referring to that very same infamous struggle for democracy between the citizens of Gwangju and the military forces of dictator Chun Doo-hwan. To learn more about this event, look no further than the coming May edition of the Gwangju News, an annual dedication issue of our magazine to those Gwangju citizens who fought for freedom. However, a look back at history will reveal that, in addition to May 18, another exceptionally momentous uprising took place in the malaise of the South Korean spring. Specifically, it was the April 19 student uprisings of 1960 in Seoul.

As T. S. Eliot pontificated in his timeless poem “The Wasteland,” April is indeed the cruelest month. The April 19 student revolution in Seoul, protesting then-president Rhee Syngman’s government, seemed to be no exception to such cruelty. The mass protests led to scores of civilian casualties at the hands of government police and military forces. Known to many by the numerical classification sa-il-gu (four-one-nine, 4.19), the April 19 democratic uprisings ultimately led to Rhee issuing his resignation as president a mere seven days later on April 26, 1960. The protests serve as a strong reminder of how integral Korea’s younger generation was in forging the path for a better society. But what exactly took place?

In the March 1960 presidential elections, Rhee Syngman of the Liberal Party won in a landslide with 88.7 percent of the votes. Rhee had been handpicked in 1948 by the United States government as the new republic’s commander-in-chief and, with backing from Washington, was able to secure re-election in the midst of the Korean War in 1952 and again in 1956. Though at first glance Rhee had seemed to secure another victory in 1960, the lopsided results were thanks to well-chronicled actions of election fraud by Rhee and his compatriots. On election day, members of Rhee’s Liberal Party stuffed ballot boxes and removed thousands of ballots that were in support of the opposition Democratic Party. Police officers had even fired upon opposition party supporters on their way to vote, killing a total of eight people. Citizens were of course not pleased upon hearing of such fraudulence and began taking to the streets.

One such protest took place in the southeastern city of Masan. There, protestors were met with fierce opposition as Rhee commissioned a military police crackdown to suppress the uprising. On April 11, 1960, the tortured body of Kim Chu Yol, one of the students who had participated in the Masan demonstration, was found by a local fisherman in Masan Bay. The young man appeared to have been fatally struck by police with a tear gas canister and shards of a tear gas bomb were deeply embedded in his skull. Despite efforts by Rhee to keep news of Kim’s death quiet, word quickly spread throughout the entire country, sparking what eventually became the beginning of the end for Rhee.

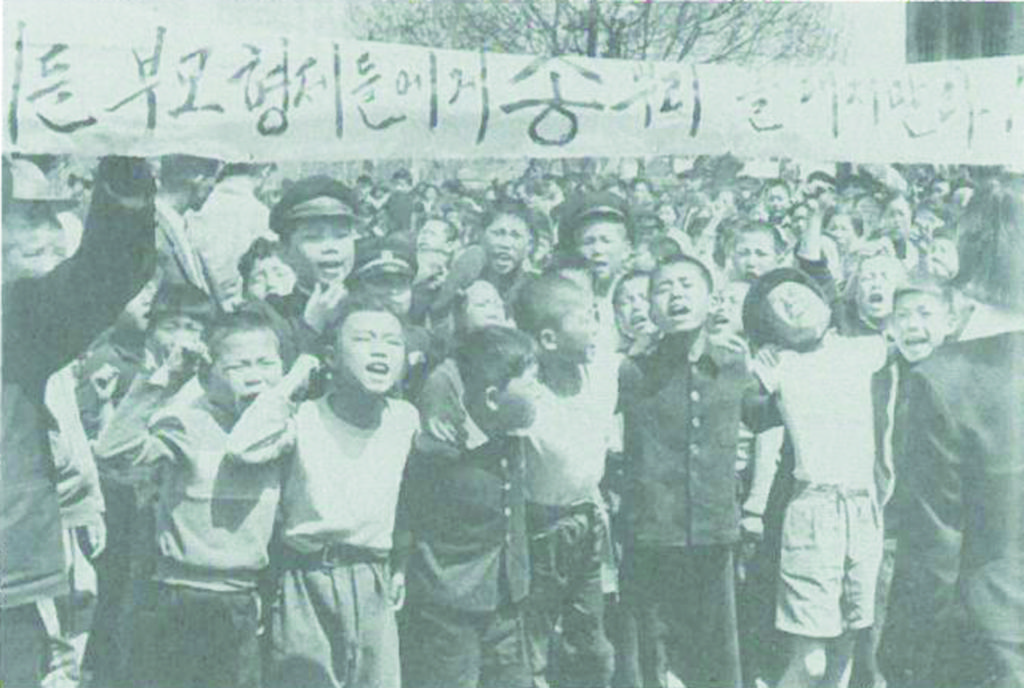

On April 18, Seoul National University students staged their own protest condemning the recent police brutality and demanding new elections. Rhee appealed to his remaining supporters within the Korean Anti-Communist Youth Organization to attack these students, which they did, causing numerous injuries. In response to the premeditated attack on the students, fellow students from Seoul National University, Yonsei University, Konkuk University, Chungang University, Kyunghee University, Dongguk University, and Sungkyunkwan University joined forces to organize a massive anti-government demonstration that very next day, the all-important April 19, 1960.

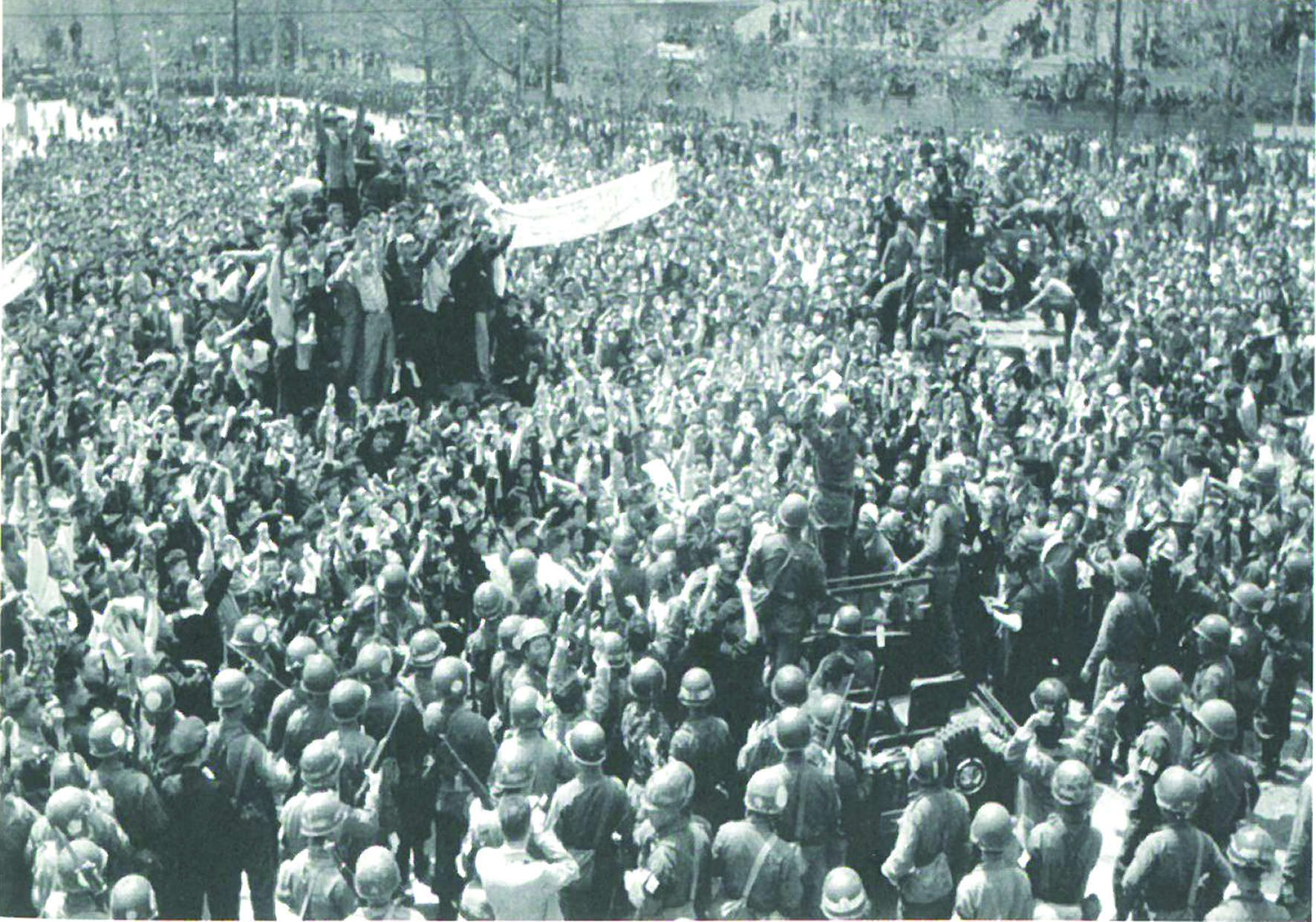

What started out as 30,000 students had by midday turned into over 100,000 Koreans filling the streets of Seoul, calling for new elections and the resignation of Rhee. The protests started at the National Assembly building and pressed on towards the presidential residence, Cheongwadae, otherwise known as the Blue House. It was at the Blue House that protesters were met and surrounded by scores of police officers. Though student leaders attempted to ensure law enforcement that their protest was non-violent and peaceful, police ordered the crowds to immediately disperse. As the demonstration continued, police fired round after round of tear gas into the crowds. Rhee declared a state of martial law and army reinforcements were sent in to administer a strict 7 p.m. curfew. Implementation of the curfew turned violent, and at the day’s end, government forces had killed 130 protesters and wounded or injured over 1,000.

In an attempt to protect his position and appease the growing number of those calling for his departure, Rhee forced all of his cabinet members and party members to resign on the following day, April 21. Additionally, on April 23, Rhee proposed a systematic reshuffling of the government as well as the reintroduction of the political post of premier to act as a further check on the president. Out of desperation, Rhee announced on April 24 that he would furthermore cut all ties with the Liberal Party. All the while protests continued in the streets, and students rejected all three proposals as such motions failed to meet their demands for a completely new election. On April 25, 300 professors joined the protest and led a mass demonstration in front of the National Assembly, whereby they announced their demands, which included most importantly the removal of Rhee. After another 15 civilians were killed and over 200 injured, martial law commander General Song Yo Chan decided enough was enough and instructed his forces to finally stop firing upon the civilians.

After losing control of the military and facing mounting pressures to step down from both the United States government in Washington as well as from a unanimous vote within the Korean National Assembly, Rhee was effectively powerless and decided to officially resign on April 26. The resignation ultimately ended the protests, and Rhee fled to exile in Hawaii.

The democratic spring of 1960 did not last long, unfortunately. An interim government created a new constitution and new elections were held in July of 1960, whereby the opposition leader, Yun Po Sun, was elected president. Yet, General Park Chung Hee seized power in a military coup in 1961, going on to rule Korea with an iron fist for the majority of the next two decades. It should be noted, however, that the significance of the April 19 uprisings should not be forgotten. Indeed, the spirit of 4.19 (sa-il-gu) is thought of as an integral stepping stone for the aforementioned Gwangju Uprising of 1980, and ultimately for Korea’s push for democratization in 1987.

The Author

Wilson Melbostad is an international human rights attorney hailing from San Francisco, California. Wilson has returned to Gwangju to undertake his newest project: the Organization for Migrant Legal Aid (OMLA), which operates out of the Gwangju International Center. He has also taken on the position of managing editor of the Gwangju News.