Remembering the Gwangju Uprising: 5.18

By C. Adam Volle.

For many, the mere mention of “May” evokes pleasant thoughts of warm weather and joyful gatherings, but to the resident of Gwangju, “O-wol” (오월, May) quickly conjures up memories of ten days in 1980 (May 18–27) when violence, gunfire, and blood dominated the city’s streets. On this 41st anniversary of the Gwangju Uprising, the Gwangju News reissues an article written by C. Adam Volle in the June 2013 issue (“Remembering the Gwangju Democratic Uprising”). At the time, Volle was the online editor of the Gwangju News and later the editor of the print edition. — Ed.

Texas has the Battle of the Alamo. Israel has the Siege of Masada. Greece has the Battle of Thermopylae. And the people of Gwangju – along with every Korean who identifies with them – have their memories of May 18–27, 1980.

The short version of the story: Thirty-three years ago [now 41 years ago], some university students in Gwangju peacefully protested against their government. A brigade of the Republic of Korea (ROK) Army responded by breaking up that protest with such violence that even uninvolved passersby were killed. This cruelty so angered the population that seemingly everyone in the city fought back and made international news by forcing the soldiers out of town. The Army eventually did regain control, but the many civilians who died in the fighting quickly became martyrs, and the event has served as an important symbol for the activists who eventually transformed South Korea into a democracy.

The longer version of the story is more difficult. During a press conference in May of 2012 about his own Uprising-inspired exhibit, Seoul photographer Noh Sun-taek reminded his audience, “The remembering [of an event] has always been accompanied with forgetting.” He meant that societies’ traumatic experiences turn into those societies’ stories, but stories have requirements that reality does not. For instance, stories can never be as complicated, especially if you want a lot of people to listen to them. So, some details are emphasized, while others are ignored, depending on the needs of the people who are speaking. The process is much like the transformation of a novel into a movie script, or multiple books and interviews into a magazine article.

With that in mind, here is the longer version.

Before May 18

The meltdown began on October 13, 1979, when Kim Young-sam lost his lawmaker’s seat in the National Assembly for saying what everyone in South Korea already knew: The National Assembly itself was a fraud since the country’s constitution gave all the power to the man who wrote it – President Park Chung-hee. Every other representative in Kim Young-sam’s National Democratic Party immediately quit in protest.

On university campuses across the country, politically minded students once again took up the chants “Down with dictatorship!” and “Protect freedom of speech!” On the night of October 15, a thousand students from Busan National University held a torchlight demonstration in downtown Busan. The experienced riot police dutifully began teargassing and beating them. This time, however, something was wrong: Rather than dispersing, the crowd just got larger. Within 24 hours, over 50,000 people surrounded Busan City Hall. The ROK Army eventually had to send specially trained paratroopers to restore order, but by then the protests had spread to Masan and Changwon. Soon, activists promised, the whole country would rise up.

This all deeply disturbed Kim Jae-kyu, the Korean CIA director, so he reported to his boss that the protests were a serious threat. According to Kim, however, President Park’s response disturbed him even more: Park said he would give the order for soldiers to break the rule against shooting civilians. He also suggested Kim was not very good at his job. Kim thought the president was not very good at his job either and advised his boss to “govern with a broader outlook.” Then Kim shot him. In the man’s own words: “‘Bang! Bang!’ Like that.”

On that night of October 26, everything changed. A majority of South Koreans already wanted government reform, but now they expected it. After all, Park Chung-hee had created the military regime; it only seemed natural that his death would end it. Foreign journalists caught the spirit of the times and began to write about a “Seoul Spring” occurring in South Korea, a period of transition soon to result in long-awaited democracy.

But as every Korean knows, the arrival of spring is always followed by a sudden chill. There is a Korean expression for it: “The winter is jealous of the flower” (꽃샘 추위). According to General John A. Wickham Jr., commander of the peninsula’s U.S. forces, many high-ranking officers in the ROK Army considered the end of their political influence to be the end of the country. They thought that military men believed in such lofty ideas as duty, honor and sacrifice, but that civilians and the media only pursued their own “selfish interests.” In particular, the generals could not imagine allowing a president with no military experience to control their armies. These “politicians in uniform” (Wickham’s term) promised they would not stop democratization, but in private, General Wickham’s sources told him differently: They planned to regain the Blue House.

Their new leader, General Chun Doo-hwan, chose a dramatic moment to make his move: the same weekend in which everyone thought the nationwide Democratic Movement had won. On Friday, May 15, Korean citizens marched all over the country, over 100,000 in Seoul, all demanding that the National Assembly finish creating a new constitution and provide a fixed date for the direct election of a new president. The Journalists Association of Korea took the opportunity to announce that its members would strike if the government did not free the press from restrictive censorship laws. Prime Minister Shin Hyeon-hwak essentially agreed to these demands, and President Choi returned early from traveling. Feeling confident, the Movement’s leaders asked all their supporters to take the weekend off. If the Assembly did not get to work on Monday, they could demonstrate again. All the protesters immediately obeyed, except for Gwangju’s.

May 18

In 1980, Dr. Dave Shaffer was working at Chosun University. “I got a phone call from Chosun University authorities saying that the university was closed until further notice to everyone – students, faculty, and staff.”

As Shaffer and the rest of Korea would later discover, a secret cabinet meeting occurred the previous night in which Chun Doo-hwan had extended martial law throughout the nation. To prevent new protests, the general ordered the arrests of activist leaders at night. He also ordered all political activities be banned, reinforced restrictions on the media, and sent paratroopers from the ROK Army’s Special Forces to close down the most troublesome universities.

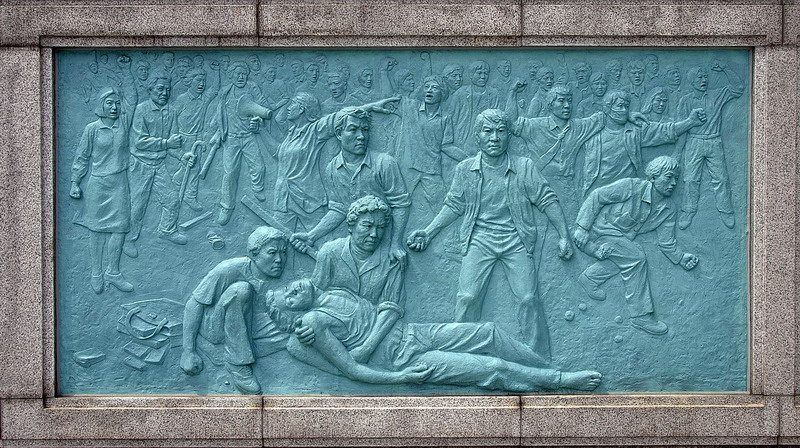

At the main gate of Chonnam National University, 30 paratroopers watched as a crowd of 300–500 students gradually amassed in the street. The soldiers wore patches identifying themselves as members of the Army’s 7th “Pegasus” Brigade, veterans of the Vietnam War usually tasked with guarding the DMZ. They carried unusual clubs. Fifty Chonnam students decided to sit down and start shouting, “End martial law!” and “Withdraw the order to close the universities!” They did not understand that these “black berets” had different intentions than in Busan; they had been given new “chungjeong” (충정) training that emphasized offense over defense. In one session, they had watched an instruction video that suggested breaking demonstrators’ collarbones and shooting anyone who ran.

The paratroopers rushed the students. Some of them put aside their clubs in favor of their daggers. Others used their guns’ bayonets. When the students ran, the soldiers followed, and while pursuing them, the soldiers also attacked anyone else they happened to see. The first person they killed was a deaf man oblivious to their presence. Many more after him were killed in ways that should not be described here. The soldiers stripped near naked those arrested and put them in trucks bound for prison camps. Multiple people later reported sexual assault. Others were never heard from again.

May 19

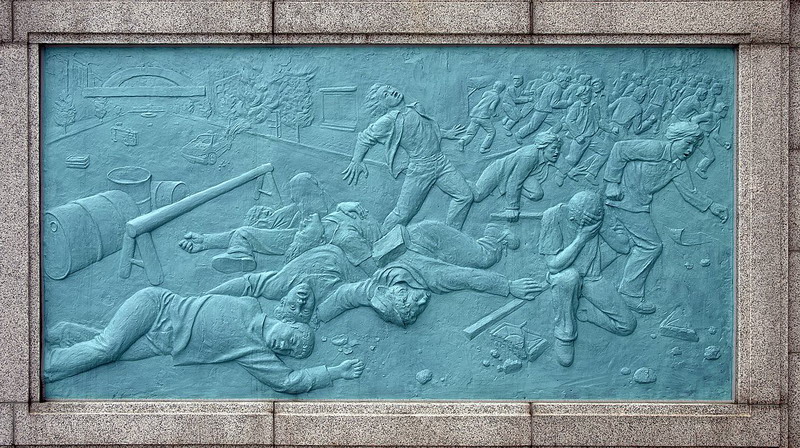

Despite the paratroopers’ aggression, the same phenomenon began occurring in Gwangju that scared Kim Jae-kyu in Busan. The crowds did not disappear; they got larger, and they fought back.

“They had only forks and spoons, only weapons found in the kitchen,” one sixth-grade student recently told the Gwangju News. The boy is not wrong. Kim Nam-ju writes of “the kitchen knives of the boys who rushed out of restaurants” in his poem “Don’t Sing of May as a Blade of Grass that Withers in Wind.”

The university students’ outraged friends and family did not limit themselves to silverware. Any handy weapon served a purpose for battle, from car tools to river stones. Some got creative by attaching their knives to the ends of bamboo poles. Others made Molotov cocktails (a firebomb requiring a bottle of kerosene or other fuel, a rag, and a lighter).

At 11 a.m., the paratroopers brought out new weapons of their own: armored vehicles, tanks, and flamethrowers. By 11 p.m., ordered reinforcements were summoned; a multitude of students from Gwangju’s male high schools had joined the fight.

May 20

A German reporter named Jürgen Hinzpeter arrived to obtain footage. He later wrote, “Never in my life, even in filming the Vietnam War, had I seen anything like this.”

Panic had begun to spread. “Kill them or they’ll kill us!” someone overheard one black beret shouting. Officers outside the city gave different advice to the fresh soldiers going in: They should show restraint to avoid further angering the population. On the Army’s loudspeakers, demands for citizens to return to their homes began to sound more like pleading. “Please return to your homes … Your families are worried about you.”

Reinforcements brought the military’s strength to just under 3,000 soldiers in addition to the already 18,000 riot police fighting, but those 21,000 men now faced over 100,000 protesters – and the number just kept growing as Gwangju residents drove their loudspeaker trucks and buses through every neighborhood, calling on every able-bodied person they saw to join the struggle. Many were pushed into action when the bodies of the dead were displayed on carts out on the streets.

At Mudeung Stadium, 200 taxi and bus drivers met to pledge their assistance, developing a strategy of driving their vehicles side-by-side up the roads where police were blocking to create moving walls that no line of riot shields could push through. By evening, a sea-like mass of demonstrators had surrounded the Army’s headquarters in the Jeollanam-do Provincial Office at the end of Geumnam Street. From its windows, the Special Forces commanders watched the city’s Tax Office burn to the ground.

May 21

“Citizens, let us save Gwangju!” Jeollanam-do’s governor shouted through his speaker, but very few people could hear his slogans over their own cheering and singing. It was 11 a.m., and below the governor’s helicopter, the multitude’s edge now laid no farther than ten meters from the Provincial Office’s defensive line.

Despite their closeness, violence between the two sides broke out only in small bursts because the people of Gwangju believed the Army was leaving. Tragically, they did not know more.

Earlier that morning, the Army had replaced its on-site commander with a new general who intended to make his name breaking the “Gwangju riot.” Shortly after 10 a.m., the new management gave each soldier guarding the Provincial Office a cartridge of real bullets and told him the secret signal on which to shoot into the crowds. The signal came at 1 p.m. sharp: Outside, the muggy air suddenly filled with a recording of Aegukga (애국가), Korea’s national anthem.

The crowd quieted. Some began to sing along. Hands rose to cover hearts.

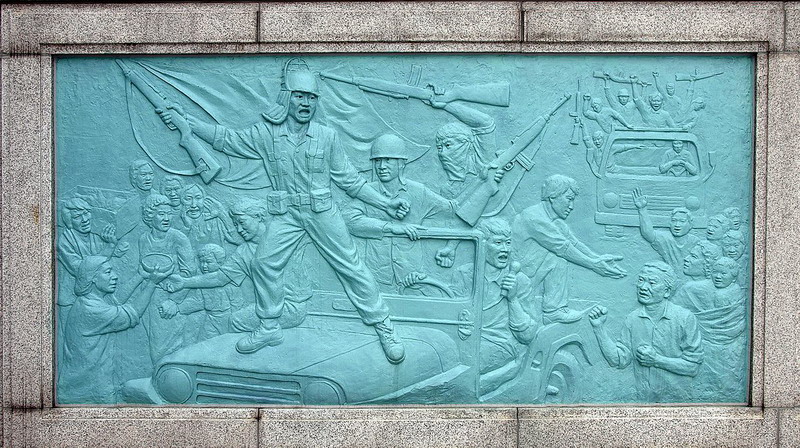

May 22–26

The soldiers’ ten-minute shooting spree killed 54, wounded more than 500 and crossed the final line; the community’s response came within two hours of that same day. Stores of M-1 carbine rifles in Gwangju’s police stations suddenly disappeared – often with the blessings of the local police – and by 3:20 p.m., the paratroopers took fire from the new “Citizens’ Army of Gwangju.” By May 22 at 5 p.m., the Army abandoned the Provincial Office to escape heavy machine gun fire. By 8 p.m., every soldier had left the city.

The resulting community of “liberated Gwangju” enjoys a near-utopian reputation in Jeollanamdo. To borrow the Bible’s description in Acts 2:44 of the first church, “All the believers were together and had everything in common.” During that time, Gwangju’s overjoyed citizens are said to have organized food distribution, cleaned up, policed their neighborhoods, and completed any other tasks without any hierarchical management. Others such as Dr. Shaffer remember a much more worrisome time and consider the standard description to be a rose-tinted view.

To help decide big questions that concerned the whole city, the people voted in meetings that attracted about 100,000 people. Those meetings became very passionate from the spontaneous nature of the Uprising. Gwangju’s residents emerged from all the excitement to realize that their city was still surrounded by tanks, they would eventually run out of food, and they did not know what to do next.

A group of prominent and respected elders in the community stepped forward to form the Citizens’ Settlement Committee (CSC), with the purpose of negotiating the city’s surrender. They hoped to obtain from the Army an apology, payment for the victims, and a promise not to punish anyone involved in the protests. As a gesture of goodwill, they began by collecting some of the guns taken by Gwangju’s protestors and gave them back to the Army in exchange for the freedom of arrested activists.

To the activists and students who had fought for ideological reasons, this course of action was crazy. If Gwangju were to give up, what would be the point of all the fighting? And how could anyone trust the government not to take its usual revenge on everyone involved? The only option was to continue the armed revolution Gwangju had already begun. To stop the “surrender faction” of the CSC, activists and students staged a sort of coup and formed their own Citizen-Student Struggle Committee (CSSC). Through a mix of good argument and physical intimidation, they took away the CSC’s power. A 29-year-old named Yun Sang-won became their spokesman.

“Yun Sang-won was maybe the only one who had a strategic view,” an activist later told reporter Bradley Martin. Yun believed nobody would remember Gwangju as an example if its uprising ended with a simple surrender. “[He] wanted to complete the rebellion, put the final touch on it.” That final touch would result in his death.

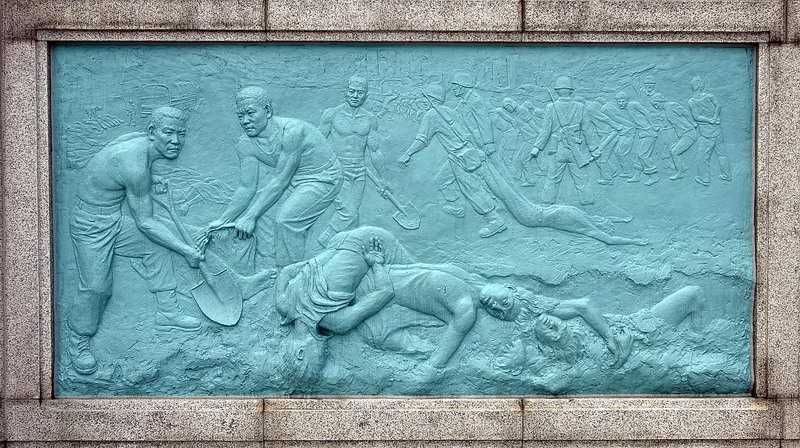

May 26–27: The Massacre

“We declare to the nation that 800,000 Gwangju citizens will fight to the end!” read the CSSC’s resolution at Democracy Square meeting on May 26. When the end did come, in fact, the CSSC discovered it had spoken for roughly 200.

Of those, the CSSC sent home about 50 women, girls, and boys, leaving “80 people who had completed military service, 60 youth and high school students, and 10 women” (George Katsiaficas in Asian Unknown Uprisings: South Korean Social Movements in the 20th Century). The remaining 150 barricaded themselves inside the Provincial Office and settled into their positions. The ROK Army’s operation began at roughly 2 a.m. in the early hours of May 27. Its tanks drew up to the Provincial Office around 4:30 a.m. while paratroopers attacked through the rear entrance. With many of the CCSC members having ten minutes of training in using their weapons, the battle did not last long. The government would later declare that two soldiers and 17 CSSC members died in the fighting. Yoon Sang-won was shot in the kidney and then burned to death by a fire.

However, the desired effect of his sacrifice soon began to materialize. “Chun Doo-hwan’s position seems less secure,” General Wickham reported to Washington, D.C., soon after.

“Chun Doo-hwan is a marked man,” the German newspaper Suddeutsche Zeitung declared more bluntly on May 30.

The new leaders of South Korea never fully recovered from Gwangju’s ruining of their debut. They lost effective power seven years later.

Special thanks to Dr. Dave Shaffer, Yoon Sang Soo, and Tim Whitman.

Arranged by David Shaffer.