Kim Geun-tae: 100 Meters of Art

By Kang Jennis Hyun-suk

A few years ago, there was a Korean artist who held an exhibition at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. UN ambassadors from many countries attended the exhibition to mark World Disabled People’s Day on December 3.

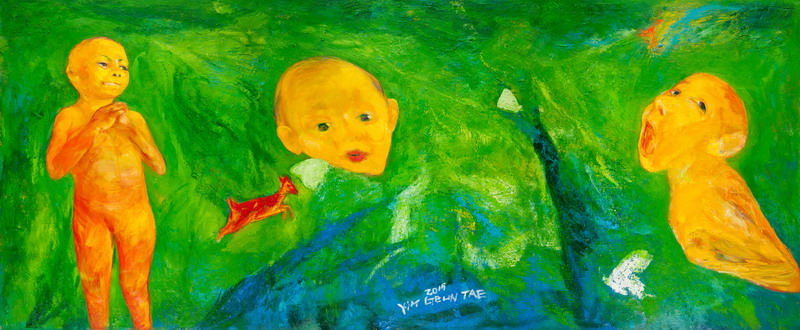

The artist, Kim Geun-tae, painted a huge work of art with an unfamiliar theme. The 100-meter-long artwork consisted of 77 large paintings of children with mental handicaps. At the invitation of UN Ambassador Oh Joon, who was the chairman of the Convention on the Rights of the Disabled, Kim’s paintings were also exhibited in Geneva and Paris.

In 2020, Kim Geun-tae exhibited his artworks under the theme of “May, Starry Wildflower” at the Asia Culture Center (ACC) in Gwangju. The ACC was built on the very block where the Jeollanam-do Provincial Office was located in 1980. The main building of the Provincial Office still stands as the historical site where the Gwangju Uprising came to a bloody end, symbolizing the spirit of democracy not only for the citizens of Gwangju but for many other citizens in the world.

Kim Geun-tae’s exhibition at the ACC triggered memories of four decades earlier. Back in May of 1980, Kim was one of the last remaining members of the civilian resistance who had taken over the Provincial Office, where they were to make their last stand. On May 26, there were rumors going around that the martial law troops were coming back into the heart of downtown to sweep away the resistance. That night, a brave female (who passed away this past February) picked up a microphone and shouted into the loudspeakers, “Citizens, help us. Citizens, let’s fight together.” Kim knew that that night might be the last of the fighting, as the small group of armed protesters were greatly outnumbered by the much better-armed military. But Kim could not forget his mother’s pleading, “Save your life!” In the darkness that night, he put down his gun and left the Provincial Office with a comrade.

Kim hid in his studio, and there he heard the nearby footsteps of soldiers. He still cannot erase from memory the sound of gunfire and screaming that he heard as the military troops made their final assault on the Provincial Office under darkness in the very early hours of May 27. He has lived his whole life with remorse for not being with his colleagues who resisted to the end against soldiers who had indiscriminately killed so many Gwangju citizens. But survivor’s guilt affected all Gwangju citizens who listened to the soldiers’ footsteps and gunfire that night in helplessness.

Kim soon graduated from the College of Art at Chosun University, carrying the scars of May 18, and started to work as an art teacher at a high school in Mokpo. However, the sound of “You coward!” haunted him every day and night. Unable to live a regular daily life, he quit teaching and went to France.

Because of Kim Geun-tae’s harrowing experience, I wanted to interview the artist for the May issue of the Gwangju News. So, I called him to arrange for an interview. His son answered the phone and said that his father was losing his hearing. A few days later, I headed towards Mokpo to interview Kim with his wife at his studio in Muan (southwest of Gwangju).

The Interview

Jennis: Thank you for giving your precious time. I have researched you and your artworks, but I want to learn more. You have said you went to Paris after marriage. How did you spend your time in France?

Kim Geun-tae: I painted and painted human bodies at the Grand Chaumiere Academy. While painting, I constantly thought about humans, why we were born, and what we really are.

Jennis: It sounds like you took the time to find yourself while studying in Paris. What made you come back to Korea?

Kim Geun-tae: I was crazy about painting in Paris. It was a time when I could forget myself. But I was sorry for my wife, who was supporting me by working as a teacher in an elementary school. I came back to Korea because I could no longer put such a financial burden on her.

Jennis: How was your life back in Korea?

Kim Geun-tae: I continued to paint human bodies after coming back to Korea. I wanted to paint the human body rather than beautiful landscapes. I tried to find myself through the hurt of others. I heard that there were severely disabled children living on the island of Gohwa-do near Mokpo. So, I went to the island. Now, there is a bridge between Mokpo and the island, but at the time, I had to access the island by boat. I stayed there with the children for three years.

Jennis: What did you do there?

Kim Geun-tae: There were children who lay on their backs and only looked up at the sky all their lives. I ate with my friends [Kim called the children his “friends”], and I tried to look at the world through their eyes. The children were born as innocent human beings but abandoned by the world. Looking into their clear eyes, I felt that they were true humans or angels who did not even know the words hate or kill. While staying with the children, I felt myself being cured of my trauma. I felt that the eyes of the children revealed their souls like wildflowers.

Jennis: You were living with them and painting them. Three years is not a short time. And you usually used red, yellow, and blue colors in your paintings. Is there a particular reason for this?

Kim Geun-tae: I have a reason for choosing the primary colors. Like language, paintings also look luxurious if ambiguous colors are used. The more you hide who you are, the more sophisticated you look. People hide their true colors behind gray. I wanted to express innocence and clearness with nothing to hide.

Jennis: What are people’s general reactions to your paintings?

Kim Geun-tae: The public was not familiar with paintings of disabled children. Nevertheless, I painted my “friends” in large-sized paintings and held an exhibition in Insa-dong in Seoul under the theme of “Like Wildflowers, Like Stars.”

Jennis: How were you able to exhibit your works at the United Nations in New York?

Kim Geun-tae: I believed that even though my paintings were not well understood in Korea, there might be people in the outside world who could understand them. And I wanted to one day exhibit in places like the Pompidou Center in Paris and MoMA [the Museum of Modern Art] in New York. Some people appreciating my paintings in Insa-dong suggested that I have an exhibition at the United Nations Headquarters in New York. Without knowing if there was a large space at the UN, I dreamed of creating a 100-meter-long exhibit of artwork there. And, one by one, people helped me to realize this. One person sent my profile of artworks to the UN and made a request for an exhibition for me. Another one lent me a vacant space to create large-sized paintings. At last, my dreams came true: Lee Nak-yeon, the governor of Jeollanam-do at that time, and Oh Joon, ambassador to the United Nations, recognized the meaning of my works and helped me exhibit them at the UN.

Jennis: What a story! They had an eye for the meaning in your art. You said your 100-meter-long artwork was made up of 77 large paintings. How long does it take to paint a work 100 meters long?

Kim Geun-tae: It took me almost three years to finish the 100 meters of paintings, and it took a lot of paint to paint such large paintings. With my wife’s support, I was able to finish my paintings for the exhibition in New York.

Jennis: I heard that your eyesight and hearing are failing. What effect has this had on your life?

Kim Geun-tae: I have been living without looking after my body, and that is why my eyesight and hearing have been deteriorating. People have worried about my lack of care for my body, but now I can better understand my “friends.” I have tried to die four times because of the May 18 trauma. Then one day, I suddenly realized that it should be my mission to deliver the message that the people who have passed away wanted to convey to the world. In this world of lookism, I have gotten a lot of messages from the children, who have the essence of beautiful human beings. Through my experience, I have come to think of opening an art healing center.

Jennis: I have heard from scholars and practitioners that art has healing powers. Do you mean you want to use painting for therapy for disabled children?

Kim Geun-tae: No, it is rather the opposite. Until now, disabled children have been objectified. But who can have clearer eyes and a clearer mind than the children? I think the treatment is needed for the people of the world with wounded souls. COVID-19 is a warning to a world that is divided into “useful” and “useless.” We have to think about what the message is that this pandemic has thrown upon mankind.

Jennis: And what do you think the message is that COVID-19 has sent us?

Kim Geun-tae: In a faster and closer world, each of us is becoming more isolated and alienated. All the world communicates only with money. The prospects for a person’s life are so often impeded by the priority given to the interests of an organization or the interests of a nation. It has caused wars and sickened the Earth. We are losing the meaning of existence, of what the most precious value in human life is. So, I thought we needed a window of communication where the world could become one.

Jennis: So, you created a corporation called “Kim Geun-tae and Friends of the Five Continents.” What specifically does the organization do?

Kim Geun-tae: “Kim Geun-tae and Friends of the Five Continents” gathered paintings of disabled children living on five continents and held exhibitions to commemorate the Pyeongchang Winter Paralympics. I hope that “Kim Geun-tae and Friends of the Five Continents” will take a step further toward peace on the divided Korean Peninsula and toward world peace through art.

After the Interview

The Jeollanamdo Art Museum in Gwangyang opened last March. The museum has bought Kim Geun-tae’s 100-meter artwork as a collection. Now, he is dreaming of someday exhibiting 200 meters of paintings at MoMA in New York or at the Pompidou Center in Paris. Just as with van Gogh and Theo, I think that Kim Geun-tae has been able to create his artwork with the support of his wife, Choi Hosoon. During the interview, I sensed that their relationship is beyond merely that of wife and husband. I respect both of them for walking on the path of world peace through art. I am looking forward to seeing Kim Geun-tae’s paintings of peace at MoMA or the Pompidou Center someday.

Photographs courtesy of Kim Geun-tae.

For more art and information on Kim Geun-tae, go to his website at http://m.kimgeuntae.com/

The Author

Kang Jennis Hyunsuk is a freelance interpreter who loves to read books and take photos of nature. She has been living in Gwangju all her life. She loves to talk with old ladies in the Jeolla dialect in the rural markets. Jennis feels sorry that the precious history-bearing dialects of the ancestors are fading away. She is surely a lover of Gwangju.