Singing of the Abode of the Wind – Artist Kim Kyung-joo

By Kang “Jennis” Hyunsuk

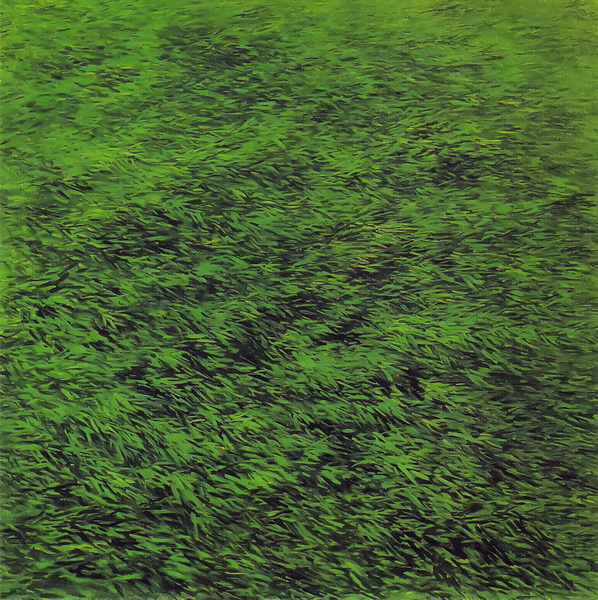

“As a child, I thought that all the wind on this earth was lurking in its bamboo forests. How could I not think of the bamboo forest as the abode of the wind when I heard the snowstorm rattle the leaves of the bamboo so harshly in winter or when I heard the soft rustling of bamboo leaves in summer? I remember that I used to enter a nearby bamboo grove that I believed harbored something mysterious. And the cave near the bamboo grove, which three or four men could fit into, was also an object of curiosity and fear for me. People said that the blooming of the bamboo foretells of a surprising disaster. But they also believed that the divine protection of the bamboo forest would protect those who hid in it. Ever since I heard grown-ups talking in whispers about several people who saved their lives from rifle bullets by hiding among the bamboo, I have been keeping this story of the mysterious bamboo forest in my mind.” — Kim Kyung-joo

In this installment of People in the Arts, we meet artist Kim Kyung-joo, who founded the Gwangju-Jeonnam Art Community and was a participant in the minjung art movement with woodblock prints and ink paintings. What follows is the interview that I recently had with Mr. Kim.

Jennis: Thank you for allowing me to do this interview. I would like to hear about your history in painting – how you came into the world of art when you were young.

Kim Kyung-joo: I was born in Gangjin and spent my childhood in nature. My aunt, who lived in Gwangju, gave me painting materials as a gift when she visited us. So, painting became my hobby. When I went to middle school in Gwangju, the art teacher suggested that I join the art club when he saw my drawings. On his recommendation, I also joined the art club in high school.

Jennis: You must have naturally majored in painting in college.

Kim Kyung-joo: I did not get the score I wanted on the college entrance exam, so I entered a design school instead of an art college. There was a professor there who often gave us essay writing homework. She recommended that I take the reporter’s test for a newspaper company, saying that I had a talent for writing. Thanks to that professor, I became a reporter for the Chonnam Daily newspaper. After working as a journalist for about two years, I went to the army. However, in the late 1970s, reporters had a military exemption, requiring only four weeks of simple military training. But I wanted to do the full period of military service like other young men.

Jennis: So, you declined that exemption and volunteered for the military?

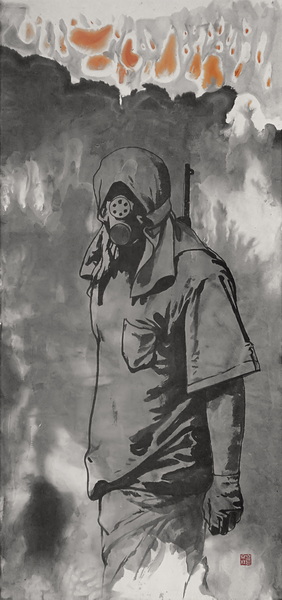

Kim Kyung-joo: Yes, and when I was serving in the army, the May 18 Uprising occurred in Gwangju in 1980. The news said that the protesters in Gwangju were rioting, but all the phone lines in Gwangju were cut off, so I had no idea how all my family and friends were doing. My senior officer’s hometown was also Gwangju, so we were worried as we listened to the radio. When people said that the Gwangju rioting was suppressed, my senior officer gave me leave to find out how my and some of my fellow soldiers’ families were doing.

When I got there, I was surprised to see quiet streets and quiet people in Gwangju – as if nothing had happened. The combat police, standing at every street corner and wearing thick armor, were the only remnants of the May 18 Uprising. At the time, media consolidation was carried out by the Chun Doo-hwan regime. This was done to make the journalists who were resistant conform to his system.

“We saw, we clearly saw, with our own eyes that people were being dragged and dying like dogs. But we are not allowed to write a single line about this in the newspaper. Therefore, we are ashamed, and we put down our pens.” The senior journalists of the Chonnam Daily read this statement and submitted their resignations. It was impressive that senior journalists, who had young children to support, made such a decision.

Jennis: Then you also had no job to go back to after your military service.

Kim Kyung-joo: Right. I joined a group to make a collection of poems about May 18. At that time, it was not easy to say the word “May” (오월) under the military regime. Nevertheless, I joined in the work of making poems of May into woodblock prints. The engravings might be considered my first work as an artist. The book of poetry and accompanying woodblock prints spread to universities across the country, and an agent from the National Security Department came from Seoul to keep an eye on me and my daily life.

Jennis: Could you tell me why you chose the medium of woodcuts?

Kim Kyung-joo: Because there were so many things that I wanted to say to the world. But painting is only a single item. Paintings in a gallery can only be seen by the gallery visitors. However, the woodcut prints could be spread widely, and my prints were used in some universities as book cover designs or as hanging wall prints.

In 1983, I had my first exhibition of May 18 woodblock prints. At the time, Prof. Yu Hong-jun, an art critic who wrote the book Exploration of My Cultural Heritage, came to Gwangju to interview me. Even though I said I did not have anything to show him, he wrote for a magazine my story about engraving on the theme of May 18. At the time, it was difficult for people to talk about May 18, so that is probably why he wanted to write on the topic. Due to that relationship, when I held my second exhibition in 1985, Prof. Lee Tae-ho and Prof. Yu both came and gave special lectures.

Jennis: I also learned Korean art history from Prof. Lee, and he helped me open my eyes to the art of this land where I live, not the art of some distant country. I heard his name several times from the artists in Gwangju that I have interviewed.

Kim Kyung-joo: Prof. Lee has done a lot of work in the Gwangju and Jeollanam-do world of art. He is the one who has been with me for an unforgettable period of time. I think Prof. Lee, who has always been happy to do lectures, is the most influential person in the Gwangju art scene.

At that time, many people who wanted to go forward with a cultural movement founded the People’s Culture Research. This cultural movement was to promote the May 18 Uprising to the world with songs, plays, and paintings. One day, I was reading the poem Song by the activist poet Kim Nam-ju (1946–1994), who “sang” of the uprising of the Donghak Peasants in the late Joseon Dynasty. I thought that the poem might want to actually be sung, so I wrote the score for Jukchang-ga (죽창가, Song of the Bamboo Spear) for the guitar.

Jennis: A few years ago, there was a scene in a TV drama of people singing Jukchang-ga. It is amazing that you are the composer of that famous song. Getting back to your artworks, you have changed your medium from woodblock prints to ink and wash paintings. What is the reason for your change in media?

Kim Kyung-joo: Prof. Lee, who sometimes stopped by my small studio, recommended that I do ink and wash paintings. Oil paintings can be modified through the process of overlaying, but ink and wash painting done on thin paper is not easy to modify. Nevertheless, I thought that ink and wash painting was a better medium for expressing our emotions.

Jennis: What is the most memorable work among your ink paintings?

Kim Kyung-joo: The artists in Gwangju who were interested in promoting the social role of art formed the Gwangju-Jeonnam Art Community. On the tenth anniversary of May 18, we held an exhibition under the theme “10 Days of Uprising, 10 Years of History.” It caused a great wave at the time.

Jennis: Among your artworks, there is one that is titled If It’s a Mountain, It’s Mudeung. There are many paintings of Mudeung Mountain by other artists, but when I saw your painting of Mudeung Mountain, I felt as if I were looking down from above. It was grand and pleasing to the eye. How did that work come about?

Kim Kyung-joo: Not long after I started ink and wash painting on my own, I read the poem Song by Kim Nam-ju. It included the words “Behold, Mt. Mudeung / If you sit down, all other mountains sit with you. / Behold, Mt. Mudeung / When you stand up, all others stand up in waves.” I felt a stirring sensation overtaking my entire body from reading those words. And I completed the painting in just an hour.

Jennis:I heard that you have worked as a professor at Dongshin University and did a lot of work there. How was your time at the university?

Kim Kyung-joo: One day, President Lee Sang-seop of Dongshin University came to my studio. In his hand, he had a book entitled The Artists of Our Time: 22 People. Then he asked me if I was the Kim Kyung-joo in 22 People. He often stopped by to see my works. That day, he suggested that I work with him, but I immediately declined to work as a professor. After some thought, though, as to how I could raise my children as a painter, I applied for the professorship. However, I was most sorry to my colleagues who I had worked with in the Gwangju-Jeonnam Art Community.

At Dongshin University, I opened a museum and lectured in art courses; I even did relentless promotional planning, which took its toll on my health.

Jennis: You have gone through several changes of medium – from oil paintings and woodblock prints to ink and wash paintings, and you even composed music. I heard that many artists have synesthesia, and I think you must have it also. Can I ask what future direction your art might take?

Kim Kyung-joo: I want to paint through the feeling of the five senses. But I want to filter out the extraneous things that come to me and do minimalist painting – simple synesthesia.

Jennis: Thank you for this extensive and quite interesting interview.

After the Interview

Artist Kim Kyung-joo has constantly been practicing the mission of his first job, as a journalist, but in a different way. He has consistently carried out his mission as a messenger in a wide range of fields: as a painter, poet, composer, social activist, educator, and exhibition planner. And they all have art as their common denominator. Kim says that he wants to create a simple but emotional resonance in his paintings. After the interview, I have thought deeply about the message he strives to tell us. And now it is May once again.

The Author/Interviewer

Jennis Kang is a lifelong resident of Gwangju. She has been doing oil painting for almost a decade, and she has learned that there are a lot of fabulous artists in this City of Art. As a freelance interpreter and translator, her desire is to introduce these wonderful artists to the world. Instagram: @jenniskang