Painting What Talks to Him – The Master of Ink, Kim Ho-suk

By Kang “Jennis” Hyunsuk

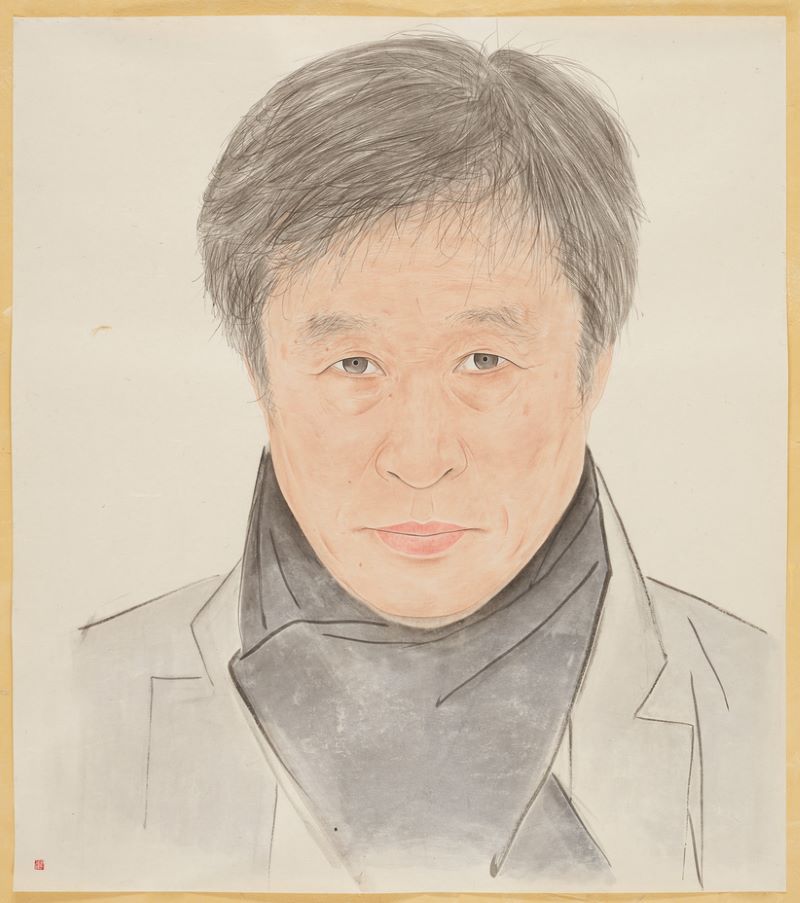

In this article for People in the Arts, I introduce Kim Ho-suk, who is having an invitational exhibition at the Gwangju Museum of Art throughout the summer. The artist’s warm gaze at his growing children, aging wife, and aged parents conveys emotion to those who view his paintings. He also metaphorically expresses the absurdity of our society through animals and insects. Artist Kim Ho-suk has found a way to make traditional Korean paper, hanji, accommodate in his paintings the portrait technique of the Joseon Dynasty period. I was able to interview him in Seoul’s Sinchon District at around the time he finished his work. The artist keeps working hours from 9–3 as a daily routine. Here is what we discussed.

The Interview

Jennis: Thank you for this interview for People in the Arts in the Gwangju News. I was really moved by your exhibition at the Gwangju Museum of Art, which led to my asking for this interview.

Kim Ho-suk: Thank you for coming all this way.

Jennis: This is a question I always ask when I interview an artist: I wonder what motivated you to become an artist. What was your childhood like?

Kim Ho-suk:I spent my childhood in Jeongeup in Jeollabuk-do. My great-great-grandfather, Chunujeong, Kim Young-Sang (1836–1911), who was a Confucian scholar, refused the monetary award given by the Japanese government for conciliation after the merger of Korea and Japan in 1910. He was arrested for committing blasphemy against the emperor of Japan for biting the arm of the Japanese police officer who handed out the written edict. On the way to Gunsan Prison across the Mangyeong River, he jumped off the boat to take his own life. Chae Yong-shin (1850–1941), the last royal court painter of the Joseon Dynasty, depicted the scene in a painting entitled Chunujeong Dives into Martyrdom. [Chunujeong died in prison two days after the incident.]

When I was young, I went to the family shrine every morning with my grandfather. I kneeled and bowed to my ancestors’ portraits and silently told what I had done the previous day and what I would do on that day. I always wondered what the secret was that moved my heart while looking at the portraits hanging in the shrine.

Jennis: At the age of five or six, you said that you wanted to be an artist who moved people’s hearts. Then, how did you study painting when you were in school?

Kim Ho-suk: I moved to Jeonju and lived there before going to university. But I had a different painting experience than most people. I did not learn painting through the process of copying someone else’s paintings; I learned to paint by myself through the observation of nature. When I see fluttering leaves, I can measure the strength of the wind. And when observing the way birds are flying, I can feel the warmth of the earth and feel that spring is nearing. When reading a book that is written in a soothing manner, it gives me something more impressive than something written in a grandiloquent style. I do not try to do paintings that are functionally good. The moment that nature lets me in, I can capture its message in my paintings.

Jennis: You majored in oriental painting at Hongik University, whose art college is famous in Korea, and you won second place in the Joong-Ang Fine Arts Contest when you were in your twenties. What kind of painting was that one?

Kim Ho-suk: That was the work titled An Apartment Building. At the time, there were few artists who painted night sceneries of the city with ink. I would say painting a night scene with ink was a kind of taboo. But art is a challenge to the taboo. And my challenge was said to be a modernistic expression of ink painting.

Jennis: You have made a change in themes from city nightscapes to portrait painting. What is the most important point in portrait painting?

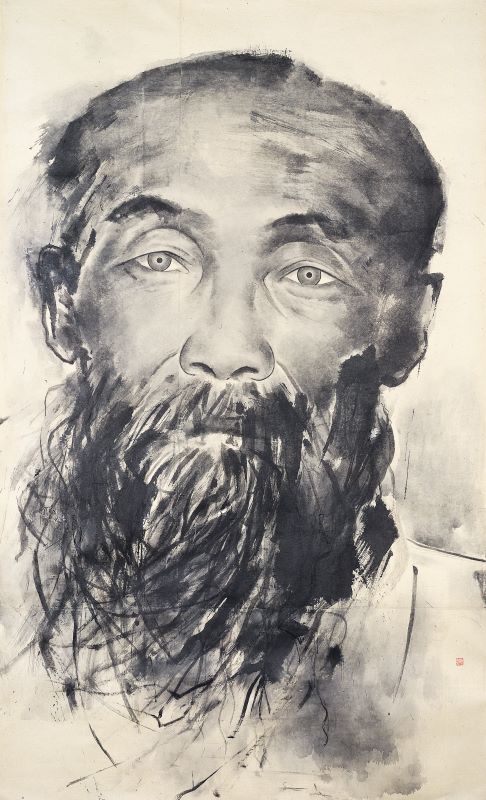

Kim Ho-suk: I wanted to talk about humans, and there seemed to be no subject that talked about humans more than portrait painting. When I paint a person, one of the most important things is to express the person’s inner world externally. From the Goryeo Dynasty to the Joseon Dynasty, there was a traditional way to do portrait painting. They colored face and hands on the back side of the paper several times for the colors to permeate through the pores of the paper. This was to express the face softly on the front side. It is called the baechae method.

However, when I tried to draw in this traditional way, the hanji could not support the weight of the thick colors on the back and the paper tore, because the mass-production method for hanji employed during the Japanese colonial era had degraded its quality. Soon the high-end hanji manufacturing system was gone. But I have discovered our traditional hanji paper manufacturing method for my painting.

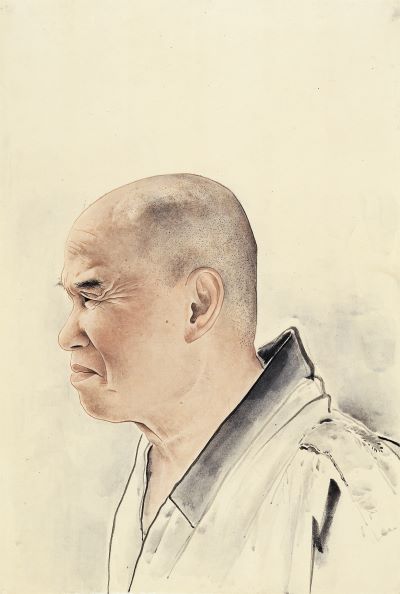

Jennis: It is amazing that you have been able to develop the quality of hanji needed for your work. In one of the many books that you have written, Every Wall Is a Door, I read that you painted Monk Seongcheol’s (1912–1993) portrait using the traditional method, baechae, which means “apply the paints hundreds of times on the back side of the painting.” And you visited Monk Seongcheol’s birthplace to acquire some soil as painting material. I think the act of collecting soil from his birthplace is itself art.

Kim Ho-suk: I would say it is a desperate craving. My desperation to depict the inner world of the characters in my paintings pushed me to find the traditional way of making hanji. Embodying in Monk Seongcheol’s portrait his mental depth was the biggest challenge for me. So, I visited his birthplace and collected some ocher soil near the kitchen fireplace. This soil is the secret of his skin color in the painting. This was a modern-day implementation of the baechae technique, the main technique used to make portraits during the Goryeo Dynasty period.

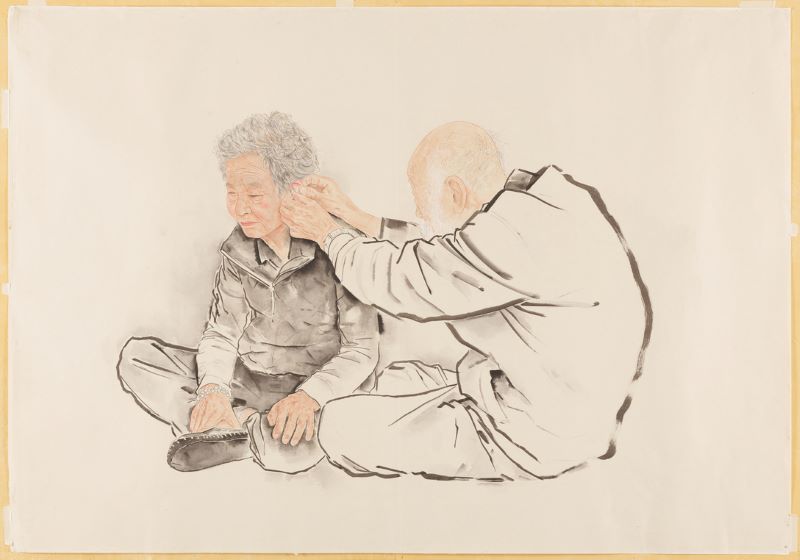

Jennis: You have painted a lot of works involving your family’s daily life, and more than 100 pieces of your artwork are in elementary, middle, and high school textbooks and teacher’s guides. This is amazing! Personally, I was touched by the work The Last Gift. What story are you telling in this painting?

Kim Ho-suk: This is the story of my parents. It is the scene when my father got sick, and he put the hearing aid he had used into my mother’s ear before he went to the hospital for surgery. My father gave the sound of the world to my mother as his last gift. But my mother was also feeble and just nodded her head without understanding what her husband was saying. I captured the moment when my heart was broken.

Jennis: I saw the painting with several gunshot holes drawn on one side and dying mosquitoes on the other side. It also contained the text: “Mosquitoes don’t suck the blood of their own species.” I was surprised to read those words. Your painting creates an impression in itself, but the exquisite phrase that you added suits the painting so well.

Kim Ho-suk: When I was young, I thought that memorizing a lot of poetry could keep my mind clear. And the poems that I memorized in my childhood come up whenever I need them. The poem of monk and independence activist Han Yong-un (1879–1944) also rose up in my heart, and I conveyed that meaning in a painting.

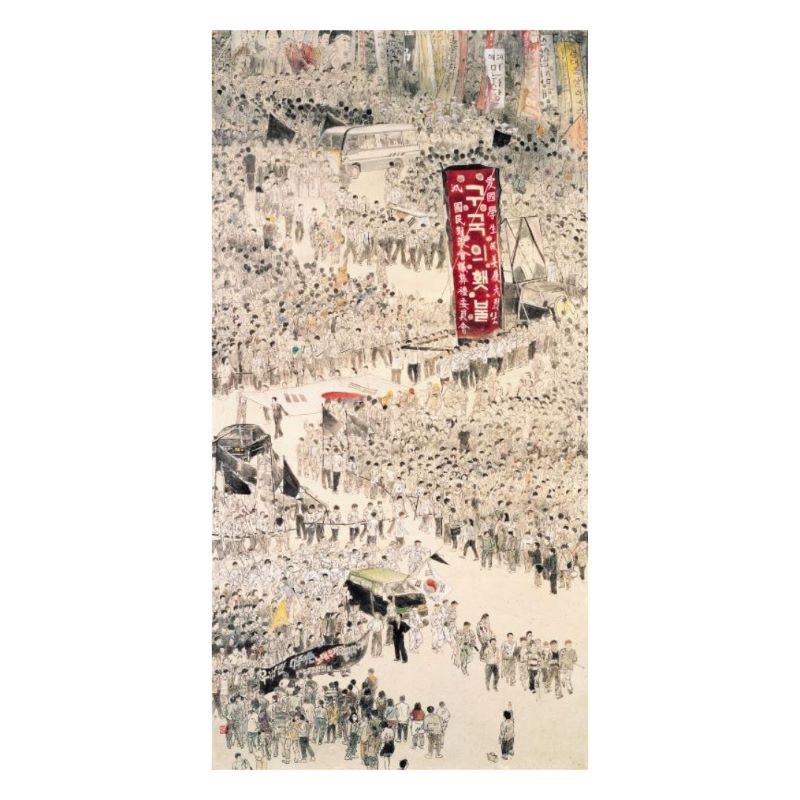

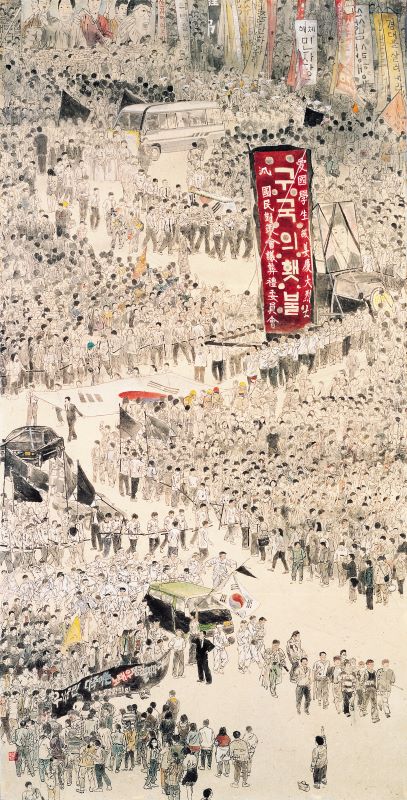

Jennis: You have painted historical paintings like May Uprising of Gwangju and From Gobu to Seoul, which depicts the protests of farmers against the institution of WTO regulations. There is also the funeral procession of Kang Kyung-dae (1972–1991), the freshman college student who was killed by riot police during a street demonstration. Most historical paintings are huge and have a large number of people in them. But the facial expressions and movements of the people in your paintings are all different. How were you able to paint so many people in one painting? I heard that it is impossible to make modifications in ink painting.

Kim Ho-suk: That is right. Once the brush goes wrong, I have to start over on a new paper, so I use the brush as if I am using the tip of a knife. I have wanted to paint the history, hope, and vision of this land. You can see the flow of time in the work A Procession of History: Beyond Death, to the Sea of Democracy.

Jennis: You have also painted a lot of historical figures. I saw the painting Resistance: Ahn Chang-ho (1878–1938), who was arrested during the independence movement and died in prison. What did you want to convey through your historical figures?

Kim Ho-suk: There is the term “righteousness.” In our country, there are people who do the righteous act at every juncture of our history. And I think the spirit of righteousness is still in our DNA. So, the most important thing in my work is sanity. I can say that the act of painting is also the process of completing myself.

Jennis: You say that your painting is part of a process of completing yourself. I think you are like a Zen master who considers the act of painting as a means of fulfillment. What would your future plans be for your painting?

Kim Ho-suk: I cannot answer that question. For me, painting is not something that is planned, but something that happens at the moment the object talks to me.

Jennis: I am sure that there will be lots of moments and lots of objects that talk to you. Thanks so much for the interview. I hope to see you again in an exhibition hall sometime soon.

After the Interview…

Maybe a wall, as in Every Wall Is a Door, is a device that allows us to realize what we really want. Artist Kim Ho-suk restored Korea’s traditional hanji paper with the desire to express the inner world of objects. Since he is an artist who has used every wall as a door, 115 pieces of his artwork can be found in public school art textbooks in Korea. I recommend that you take the opportunity to see his invitational exhibition at the Gwangju Museum of Art, which runs until August 13.

Kim Ho-suk’s Profile

1981. Graduated from Hongik University in oriental painting.

2008–2014. Professor at Korea National University of Cultural Heritage.

Publications

Aim an Arrow at Civilization, 2006.

Rock Art of Korea, 2008.

Kim Ho-suk’s Ink Painting Laugh, 2012.

History of Bangu-dae Rock Art, 2013.

Kim Ho-suk’s Ink Paintings, 2015.

Every Wall Is a Door, 2016.

Recoil of Reasoning, 2022.

Lee Kang Is Lee Kang, 2023.

Acquisitions

The National Assembly, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul Museum of Art, Ho-Am Museum of Art, Arario Museum of Art, Korean Embassy in Turkey, Korean Embassy in the Philippines, Amore Pacific Museum of Art, Heungkuk Life Insurance, Gwangju Museum of Art.