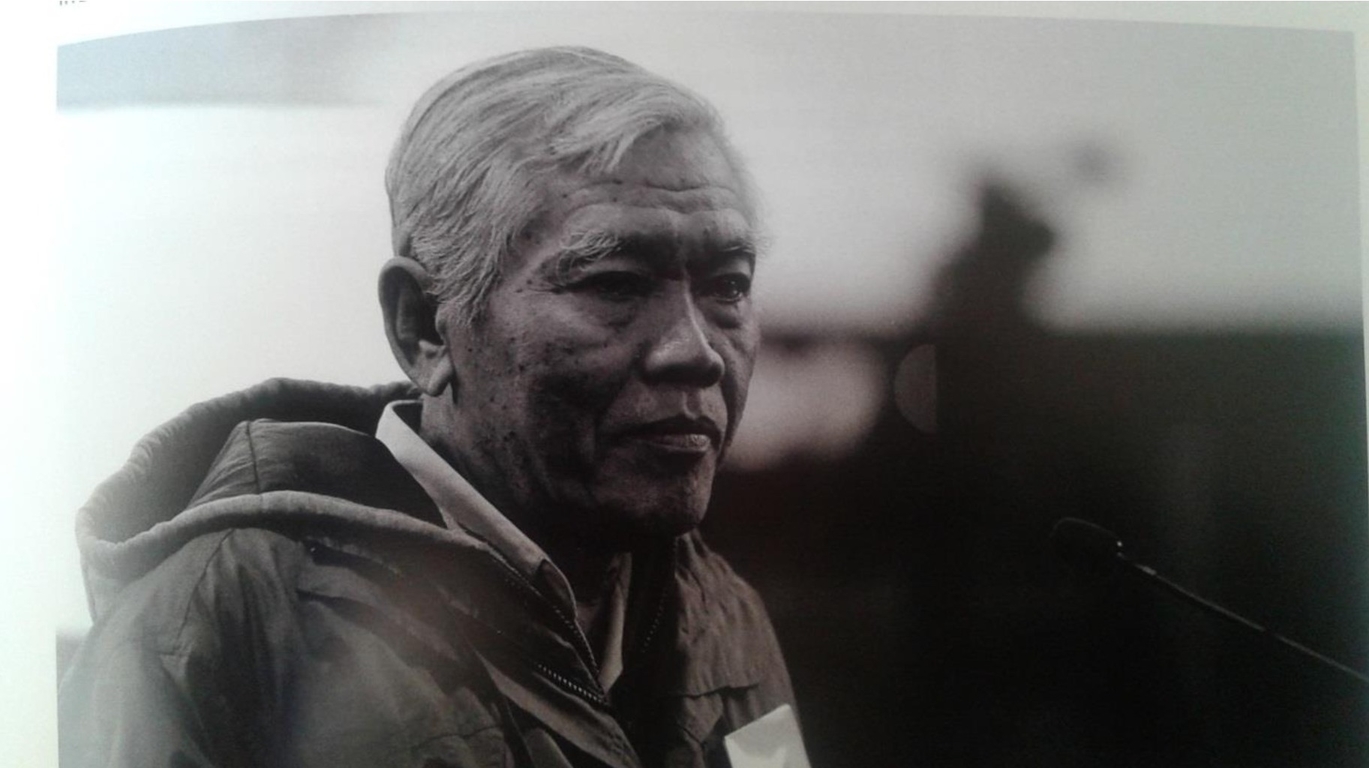

Bedjo Untung

2020 Gwangju Prize for Human Rights Awardee.

Interviewed by David Shaffer.

Photographs courtesy of Bedjo Untung.

The Gwangju Prize for Human Rights is an award given by the May 18 Memorial Foundation to an individual, group, or institution – domestic or international – for their work in furthering human rights, democracy, and peace. The award has been given annually since 2000 to commemorate the Gwangju Democratization Movement of May 1980. It has been announced that this year’s award goes to Bedjo Untung of Indonesia. While planning his May 18 visit to Gwangju to receive the award, the Gwangju News was fortunate to have the opportunity to do this interview with Mr. Bedjo. (Due to the pandemic, Mr. Bedjo’s visit to Gwangju has been set back to October, the occasion of the World Human Rights Cities Forum.) — Ed.

Gwangju News (GN): Congratulations, Mr. Bedjo, on being the 2020 recipient of the Gwangju Prize for Human Rights. Though I am sure this is not your first accolade, how does receiving this prize for human rights make you feel?

Mr. Bedjo Untung: Of course, I am happy to receive the 2020 Gwangju 5.18 Award for Democracy and Human Rights. In fact, I do not feel worthy of this award because the research, truth-telling, and recording of victims

killed and detained, and their mass graves, are the work of victims and volunteers. Without the support of the victims, this great work would not have been successful. So, this award is an award for all victims of human rights violations, especially the victims of 1965–1966. Therefore, this award is dedicated to the victims and volunteers of the YPKP 65 [1965 Murder Victims Research Foundation] who have worked hard to search for and record mass graves throughout Indonesia.

For me, this award is a form of recognition from the international community, especially the people of Gwangju, for the YPKP 65’s efforts to obtain justice for victims of the Indonesian tragedy of 1965. It is my

hope that this award from the Gwangju 5.18 Memorial Foundation will inspire and motivate nations throughout the world, especially in Asia, Korea, and Indonesia.

GN: You were jailed for the entire decade of the 1970s in Indonesia. Can you tell us what lead to this imprisonment and what conditions you had to deal with during that time?

Bedjo Untung: When the 1965 tragedy occurred, I was 17 years old and a third-year student in the High Teacher Education School. At the time, I was arrested for being a member of the IPPI (Indonesian Student Youth Association), an independent student organization, not affiliated with any political party, focusing its activities on arts, culture, sports, and joint learning. But the Suharto regime considered it as an affiliated leftist organization of the Indonesian Communist Party (IPPI). The IPPI was

indeed a student organization that supported President Sukarno’s government policies to build a just and prosperous Indonesia, create social welfare for all people, and respect human rights and democratic values as well.

At the time, my father was also arrested, detained, and finally exiled to Buru Island for 14 years for supporting President Sukarno. My uncle was killed and buried in an unknown place. Suharto’s military regime, in an effort to overthrow President Sukarno and strengthen Suharto’s

military rule, carried out acts of destruction to root out all forces that supported President Sukarno and members of the Indonesian Communist Party. According to Suharto’s right-hand man, 500,000–3,000,000 people were killed in the 1965–1966 genocide. It was the most brutal massacre

in the 20th century, following World War II.

I was tortured, forced to be naked, and then received electrical shocks to force a confession from me for things that I did not do. I was put in a narrow cell. Every night many prisoners were tortured until they were covered in blood, and they were not given proper food. I suffered

from malnutrition due to lack of food and could not walk. I was moved to a larger prison, Salemba Prison in Jakarta, and later, I was moved to a forced labor camp in Tangerang, 26 kilometers from Jakarta. We were forced

to work from 5 a.m. until sunset. Due to lack of food, we prisoners had to find our own food by consuming any animals found in the forced labor area, including lizards, snakes, mice, snails, crickets, insects, caterpillars, and leaves that grew in the camp. I was detained for nine years

from 1970 until my release in 1979.

GN: You are one of the founders of the 1965 Murder Victims Research Foundation (or YPKP 65). Please tell us what the mission of this foundation is and about the 1965–1966 events in Indonesian history that have led to

the creation of the foundation.

Bedjo Untung: The YPKP 65’s vision and mission is to reveal the truth, uphold justice, strengthen human rights and democracy, and fight for justice for victims of human rights violations, especially victims of the 1965

tragedy. The humanitarian tragedy of 1965–1966 began with a planned coup by a group of right-wing army generals against President Sukarno to coincide with the celebration of Indonesia’s Armed Forces Day on October

5, 1965. The threat of a coup by the Council of Generals was met with opposition from a group of progressive minded officers who formed the Revolutionary Council. In the early hours of the morning of October 1, 1965,

the abduction and arrest of six high-ranking officers took place by President Sukarno’s elite guard with the intention of protecting President Sukarno from the threat of a coup by the Council of Generals. Military authorities

then spread hate propaganda and false news claiming that the arrested generals were killed in the early hours of October 1 by the PKI and their bodies mutilated by members of a women’s organization that fought for the

emancipation of women. This ignited the emotions of the masses to carry out retaliatory killings of those accused of being communists.

The military used the fabricated story of the killing of generals as a pretext for mass murders. It is not surprising that Bertrand Russell, a liberal figure from England, in 1966 said that “in four months, five times as many people

died in Indonesia as in Vietnam in twelve years.” Based on the historical background of the 1965–1966 tragedy, which is still dark and full of mystery, the YPKP 65 was born to expose the lies made by Suharto’s fascist dictatorial regime so that the dark, painful, crimes against humanity that killed millions of innocent people would be clearly revealed. Let the younger generation, the next generation, learn the true history so as not to repeat the same crimes in the future.

GN: What do you consider to be the greatest accomplishments of the YPKP 65?

Bedjo Untung: I cannot say this is a major achievement of the YPKP 65 because the achievement desired by the victims is the restoration of the good names of victims and the immediate legal proceedings against human

rights criminals. However, since the fall of the Suharto dictatorial regime, there has been some important progress: (a) the 1999 law concerning human rights and the 2000 law concerning the ad-hoc human rights

court, which requires the state to provide protection and respect for victims of human rights violations and justice for victims; (b) also, the 2006 law and its revision in 2014 concerning protection of witnesses and victims in which victims of gross human rights violations are entitled to protection and to medical and psycho-social services from the state; and (c) a very special achievement of the struggle by the victims, the YPKP 65 activists, and

civil society in Indonesia has been the announcement of the findings of the investigation team on the 1965–1966 tragedy that the violence was a crime against humanity and recommended that the attorney general of Indonesia

immediately conduct an investigation and bring the perpetrators to justice.

GN: I have heard that you traveled to The Hague in 2015 to testify at the International People’s Tribunal. Would you tell us what testimony you made and what the outcome of that tribunal has been?

Bedjo Untung: In front of the panel of judges of the International People’s Tribunal at The Hague, who heard the case of the Indonesian government’s alleged involvement in the crimes of the 1965–1966 tragedy, I testified based on what I had experienced as a student who was detained, tortured, and forced into hard labor in a prison camp for nine years without legal proceedings.

I also reported on the YPKP 65’s discovery of 116 mass grave locations as well as places of detention and torture carried out by the military. That was in 2015; the locations of 356 mass graves have now been discovered. I also

reported of the excavation of one of the mass graves and the collection of victims’ testimonies. An important result of the tribunal was proof of

involvement of the military chain of command in the 1965–1966 tragedy. The tribunal finally recommended that the government of the Republic of Indonesia should express its apologies to the victims of the human rights

violations and immediately hold a human rights court to bring the human rights criminals to justice to avoid recurrence of the same type of crimes in the future.

GN: How has the human rights situation in Indonesia changed since the three decades of authoritarian rule by Suharto (1967–1998)? What do you foresee for the future of human rights in Indonesia?

Bedjo Untung: The fall of the Suharto dictatorship was greeted with euphoria by the people, as it was thought to have ended the repressive Suharto era. New legislation in favor of civil society began to be formed. An important advance when Abdurrahman (Gus Dur) became president was the freedom to embrace religion and faith. Gus Dur even apologized to the victims of the 1965 human rights tragedy. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission Act of 2004 was also established. However, after the

replacement of President Abdurrahman by Megawati, Soesilo Bambang Yudhoyono, and Joko Widodo, human rights enforcement became almost stagnant.

The keywords are “political will” and “the ability to execute it.” The legal umbrella, the law, already exists; it is only courage that is required. The investigation of human rights crimes by the National Human Rights Commission is to be carried out by the attorney general. Human rights

activists, researchers, and historians have provided sufficient evidence and facts about the existence of crimes against humanity committed by the state. The younger generation has begun to open its eyes to the true history that has been covered up by the dictatorship of Suharto. Even though we are aware of how difficult it may be to uphold human rights and democracy in the future, we remain optimistic because the legal instruments for

law enforcement are in place. There is still a glimmer of hope that the condition of human rights will be better in the future.

GN: The Gwangju Prize for Human Rights was formed to commemorate the May 18 Gwangju Uprising, a pro-democracy struggle in our city. Can you draw any parallels or striking differences between this struggle and

those that you have been involved in?

Bedjo Untung: South Korea and Indonesia have a similar historical background. South Korea had the dictatorships of Park Chung-hee and Chun Doo-hwan, while Indonesia had General Suharto, who ruled authoritatively for three decades. I can say that the Korean people, especially the residents of Gwangju, who have fought bravely and

sacrificed their lives against the dictatorial regime of Chun Doo-hwan, are also our best friends. We together have the same passion and spirit to fight against dictatorial regimes and build a nation that respects human rights

and democracy. The difference is that, in Korea after the 5.18 Gwangju

Movement, national leadership emerged that upheld the values of human rights and democracy, and continued to promote never again returning to authoritarian rule. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, none of the human rights criminals have appeared in court; even now many generals involved at the time of Suharto’s dictatorship are still holding strategic positions in the palace circle.In Indonesia, none of the human rights violations of the 1965–1966 genocide have been legally resolved.

GN: Is there anything else you would like to say to the citizens of Gwangju and the people of South Korea?

Bedjo Untung: At this opportunity, on behalf of the 1965 victims, volunteers, and the YPKP 65 Foundation, I would like to express my gratitude for the solidarity and support of the people of Gwangju and South Korea so that we can continue our research and truth-telling as well as continue the struggle for justice for human rights victims, to whom dedicate this award.