The Miner Artist, Hwang Jae-hyung: Mining for Truth

By Kang Jennis Hyunsuk

In the summer of 2016, I had the opportunity to participate in a special art class called Bokgwe 5. It was an art camp organized by the Gwangju Museum of Art. Luckily, I was able to learn from my favorite artist, Hwang Jae-hyung, who encouraged the participants by telling us that everybody has the instinct of creation. For ten days from 9 to 5, he led us in group discussions along with some theoretical classes and diverse practical classes in the arts. It has already been almost six years since that time.

One day during the art camp, we went to Paengmok Port in Jindo by bus. The families of five missing victims were still waiting at the port. The 2014 Sewol disaster had resulted in 299 casualties, most of whom were students who were on a school trip to Jeju Island. As a mother with children myself, I could not stop crying. We all cried together.

On another day, we climbed Mt. Mudeung in Gwangju and sat apart in front of a small stone, a little leaf, and then a tree. Artist Hwang had us break down the image of the objects and try to draw the original character of each with “the eyes of our mind.”

I appreciated Hwang’s efforts to have the participants realize that art is close to the ordinary individual. He is one of my most admired teachers who has led me through this fascinating world of art. So, I would like to here introduce Hwang Jae-hyung to everyone who may not know him. Artist Hwang was born in Boseong, Jeollanam-do, though he now lives in Taebaek. He is known as both a miner and an artist. I am grateful to him for agreeing to this interview.

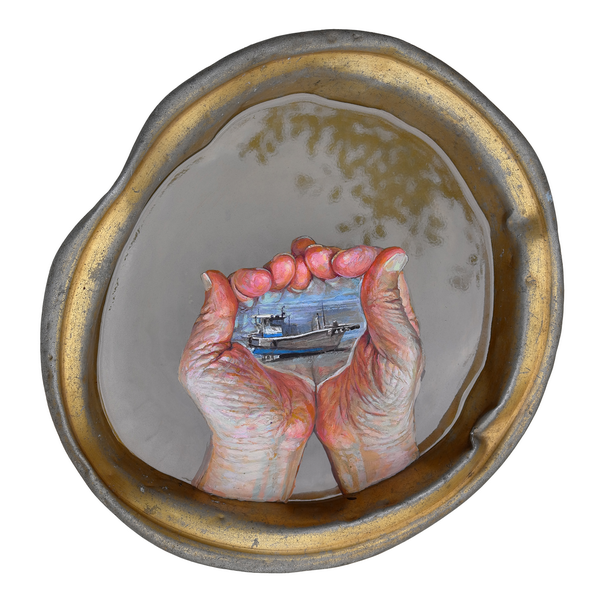

Jennis: After your four-month-long exhibition at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, I imagine you are in need of some time for a rest. But I am thankful that you are permitting this interview. I remember the day you let us share the agony of the families of the Sewol ferry victims. When we were on our way back to Gwangju, we stopped by an art exhibition in Jangheung. The exhibition was held under the theme of “Jangheung’s Story.” I still remember one of your artworks in that exhibit. It included a distorted aluminum washbasin belonging to the famous writer, Han Seung-won [the father of Han Kang, author of Human Acts, 소년이 온다). Can I ask what kind of story you put into that sorry washbasin?

Hwang Jae-hyung: The writer Han Seung-won had left Seoul and returned to his hometown, Jangheung. When I visited him, I spotted an aluminum washbasin placed near the side of the well in his yard. To me, the modest aluminum washbasin looked as if it were deserting the comforts of civilization. The position of the washbasin meant that he had to squat down in the yard to wash his face even in the cold of winter. The gelidity would spread to the whole body, but it could also awaken the mind. Just like the old scholar’s saying, “Many firsts and constant starts,” I felt that the washbasin symbolized the beginning of Han Seung-won’s new life, washing himself with the water of his hometown.

Washing with Hometown Water, by Hwang Jae-hyung (2016, acrylic on aluminum washbasin).

Jennis: I am curious about your childhood. I heard you were born in Boseong, Jeollanam-do.

Hwang Jae-hyung: That is correct. I was a child who played alone rather than with others. My family told me that as a child, I liked to draw in the white sandy beach all day long, but I do not remember that well. I moved to Gwangju when I was in the fifth grade of elementary school. At that time, I liked to draw Yun Du-seo’s (1668–1715) self-portrait, which was in our school textbook.

One day on my way to school, I saw several middle school students drawing plaster statues in a studio. Watching them through the window, I was fascinated with their statue drawings. It was my first encounter with three-dimensional drawings. I was eager to have a chance to draw. Plucking up my courage, I entered the studio and asked an adult who seemed to be a teacher, “I can draw better than anyone else if you just give me a chance.” The teacher looked a little embarrassed, but he permitted me to draw. If I had been able to draw well at that time, I would not have remembered this episode, but my first drawing of a gypsum model with charcoal was so disappointing that I wanted to die of shame at the age of 12. After that I got a chance to learn drawing, thanks to an introduction facilitated by my sister. Following this, I had the honor of winning “best prize” in the National Arts Competition when I was a middle school student. However, with my introverted personality, I had a hard time in school. When it snowed a little, my steps to school turned toward a mountain, and if the forest seemed to be cozy, I spent the day there. Only the encouraging words of several teachers who taught me painting comforted me at that time.

Jennis: You majored in fine art in Chung-Ang University in Seoul. And you have been working in realism art. So, some people call you one of the masters of Korean minjung art (the people’s art). What do you think of it?

Hwang Jae-hyung: I do not think it is meaningful to categorize art based on whether it is minjung art or not. This is because art cannot be separated by any barrier or cut with any straight edge.

Jennis: You moved to Taebaek in Gangwon Province with your wife and child, leaving Seoul and all its comforting civilization, and became a resident of a coal mining village. I wonder what prompted you to do this and how your wife accepted the process.

Hwang Jae-hyung: I once worked as a day laborer at a coal mine in Taebaek during my vacation in college. At that time, more than a few miners died in coal mine accidents. I kept one of the victim’s work clothes. He had been called by his number, “Hwangji 330,” not by his name. I wanted to record a memory of him in a painting, and that painting was over two meters tall. For that painting, I received an award at the Jung-ang Art Competition when I was a junior in college. After receiving the award for the Hwangji 330 work, I could not stop asking myself, “How do you know the feelings of miners? Are you not just pretending to know?” I felt ashamed of myself, as merely a spectator and observer. I thought that my intellectual play and ideological fiction were acts of betraying the world. So, I felt that I had no choice but to pack up to find an authentic answer to this fundamental question.

That is why I left for Taebaek with my wife and child to start a new life as a miner. About a month after I started working, my colleagues gave me a welcoming party. We sang and danced with exciting rhythms that seemed to drive away the fear in our minds. When I saw an old coal miner dancing with his bent back, I thought his wrinkled neck, dyed with the blackness of coal, was like a living record of miners. Then I felt that I was a real miner at last. After the welcoming party, my wife told me, “Now I know why you wanted to come here.” She cut off all contact with her friends and relatives and was faithful to living her life in Taebaek. I am grateful to her for walking along the way with me.

Jennis: I remember the teachers at the Taebaek Art Institute who led us with you at the art camp, Bokgwe 5. Why did you start teaching painting to Taebaek’s children and what did you want to convey to the participants through the art camp?

Hwang Jae-hyung: I think art is the totality of a life. It should be viewed as wide and long without being tied to any place. It exists in all areas of our lives. Art education as preparation to making life richer should start with obtaining life from where you are at the moment. It is more important than any theory or any teacher’s advice. Experience is not everything, but we need a foundation to give us experience.

When I was no longer able to work as a miner due to severe conjunctivitis, I was asked to teach a child with a severe disability who could not attend school. In the process of teaching that child, I learned of the healing power of art, so I taught children in need of help in every corner of the mountain village. That is how the Taebaek Art Institute began.

When I taught the children of Taebaek or through the Bokgwe art project, I wanted them to see objects with the eyes of their heart. Opening the eyes of the heart means that we stand as ourselves.

Jennis: I think the themes that run through your artworks might change with the passage of time. What do you think?

Hwang Jae-hyung: When I was a young man, I wandered, thinking about the dignity of human beings and the depth of lives. After living as a miner, another pressure bore down on me: “How can I bear the weight of the moniker ‘miner-painter?’” I drew and drew to survive, without being able to shake off my debts. I think I survived because I realized that my vocation in art was not from a god but from this society. Artists should open the drawer of darkness and catch a handful of light beyond the faintness of oblivion.

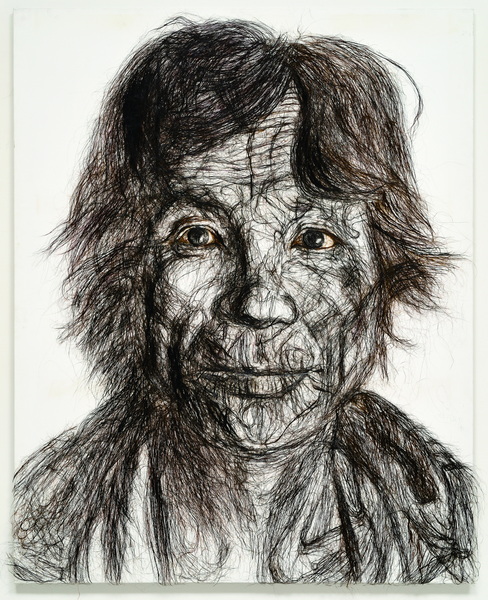

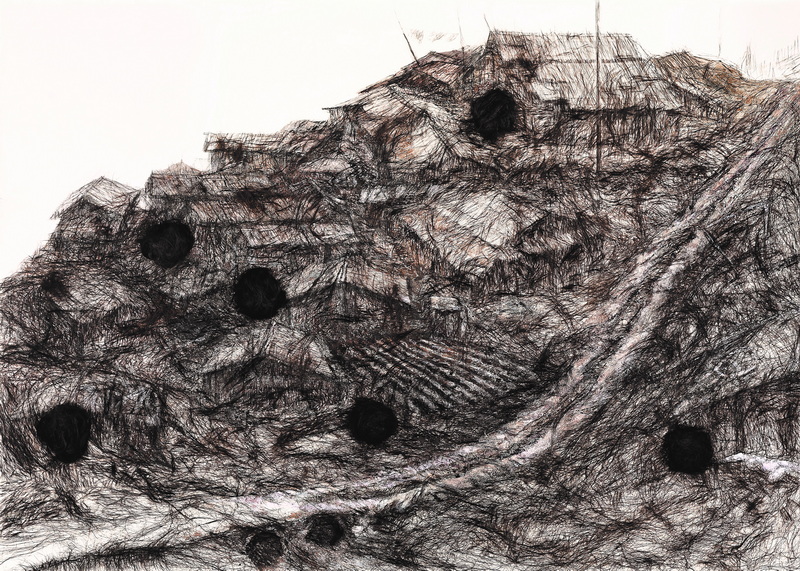

As I went to Taebaek to be a miner, I did not take with me any paints. When the aspiration to paint rose, I painted with coal powder mixed with a gel medium. Coal is definitely the most common material in Taebaek. After that, I used various materials depending on the subject of the work. One day, I wanted to create art with a miner’s hair. I heard that the human body commonly contains about 100,000 hairs. That much hair is never created in one day, and it never dies at the same time. It is a little ironic that such independent yet equal-functioning hairs growing on a human body embodies the inequality of this society. Each hair with its own vitality is a film that records the history of an individual’s life.

Jennis: What is the most memorable work of your numerous artworks and why do you consider it so?

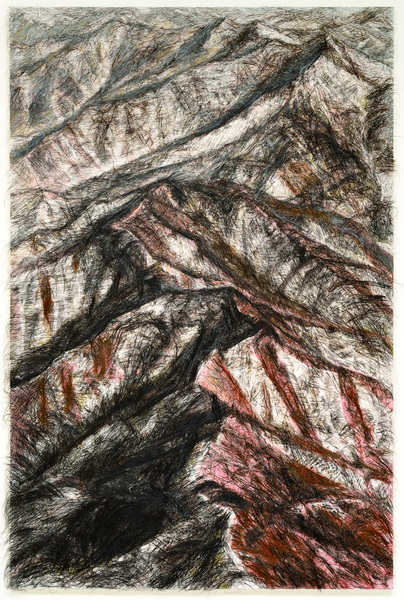

Hwang Jae-hyung: It is a work called Sambae-gugo-du (삼배구고두 / 三拜九叩頭). In 1614, when Qing China invaded the Korean Peninsula, the king of Joseon, Injo (r. 1623–1649), gave up fighting by bowing three times (sambae) and knocking his head (du) on the ground nine times (gugo). King Injo saved his life with this courtesy, but his people suffered, and some of them were even taken to China as slaves.

Everything that has life is limited by time. It has a beginning and an end. However, Henri Bergson said intrinsic time is the process of continuing with space. In Sambae-gugo-du, I expressed with human hair the mountain range as the constant space within which human time in contained. That mountain range has been lowered by being cut and crushed like an old man’s knuckles, but it contains the persistence of time, and it flows today, embodying human history.

Jennis: You had a four-month-long exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in 2021. What was the theme of the exhibition?

Hwang Jae-hyung: The title of the MMCA exhibition was “Hoecheon” (회천/回天), meaning “to turn the heavens,” allowing the heavens to turn towards the people. Lee Saek (1328–1396), a scholar of the late Goryeo Dynasty, said, “Cheon-in-mu-gan” (천인무간/天人無間), meaning that there is no gap between heaven and humankind; they are as one.

I think it is fundamental to live as the “true I” with ethical responsibility for others living together in society. We are addicted to the “need” imposed by goods in a consumerism-based society, and we are paralyzed by the illusion of “need” and suffer from a sense of poverty in our abundance. I hope that the exhibition admirers had a chance to think about what the “true I” is.

Jennis: Do you have any memorable stories from that extended exhibition?

Hwang Jae-hyung: When I was a miner in Taebaek, I painted from time to time. Sometimes my family went to the public bathhouse and then had coffee at a tearoom sitting next to a window where the sunlight came in. That was the luxury of our previous urban culture that we could not shake off. Some people had heard that I was a painter, and one day a person who was opening a tearoom wanted to buy one of my paintings. We settled on the painting Miners’ Lunch. When she went to Insa-dong in Seoul to have the painting framed, the shop owner asked her to sell the painting for double the price she had paid. Returning to Taebaek without selling the painting, even after being offered ten times the original price, she became a goodwill ambassador of my paintings in Taebaek. I do not know where she lives now, but I expected that since she liked my old works, she might have gone to see my exhibition at the MMCA.

Jennis: Do you have any future plans, or dreams, for your artwork?

Hwang Jae-hyung: Art is an intermittent cough that shares the pain of others, and it is the talk of pain. As a pilgrim of life, even if I have to endure the fate of standing in front of a new asceticism, I can have hope for tomorrow’s life if another person’s closed door opens again with my meager light. I hope that my art can serve as a love letter to some anonymous individual. Bertolt Brecht said that all human happiness depends on the happiness of others.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Curator Lim Jong-young of the Gwangju Museum of Art for putting me in touch with Artist Hwang Jae-hyung. I greatly appreciated this, and I appreciate Artist Hwang’s sincere answers to my interview questions. I felt as if I were talking with a philosopher or a clergyman who allowed me to contemplate what my “true I” is.

Photographs courtesy of Hwang Jae-hyung.

The Interviewer

Kang Jennis Hyunsuk has been living in Gwangju all her life. She has painted as a hobby for almost a decade, and she has learned that there are so many wonderful artists in Korea. As a freelance interpreter, she would like to introduce the English-speaking world to the diverse sphere of Korean art.

Instagram @jenniskang