Beeswax, Plum Blossoms, and Tea: The Works and Ways of Artist Kim Chang-deok

By Kang Jennis Hyun-suk

I think most people living in Korea have heard that the tea plantations in Boseong are one of the must-see locations in the country. The endless rows of tea plants on the plantations give us wonderful views and photographs. In Korea, most tea is grown in the low mountains of South Jeolla Province, in places like Boseong, Yeongam, Jangheung, Naju, and Mt. Mudeung in Gwangju. Hadong-gun, which is close to Mt. Jiri is also famous for its wild tea. Luckily, I had a chance to make green tea at a temple named Bulhoe-sa in Naju years ago. I learned that tea makers should not use fragrant cosmetics, soap, or shampoo because tea leaves can become coated with their fragrance.

In East Asia, food materials are divided into two main types: materials having cold energy and materials having warm energy. Most Asians believe that cooking allows the materials to be in harmony. Green tea grows well with a little moisture, so it has cold energy. Cold-energy foods can cause stomachaches if eaten cold. Making green tea is the process of reducing the cold energy from the tea leaves. It takes considerable time, but here is a brief introduction to the process:

- Begin by warming the tea leaves in a large iron pot.

- Rub the warmed tea leaves against a thick cloth or straw mat.

- Put the tea leaves in the large iron pot again and stir, turning the leaves over to enhance evaporation.

- Spread the lightly baked leaves on hanji (한지, traditional Korean paper) and dry.

- Repeat steps 1–3 nine times. When the moisture is low, only steps 2–3 are needed: heating in the pot and spreading for drying.

- When the color of the tea leaves turns black, elimination of the cold energy is complete.

Especially with large batches of tea leaves, making handmade green tea requires physical strength, taking about 8–10 continuous hours. So, some tea makers do variations on the tea-making process. They might bake the tea leaves once or twice at a high temperature. Some tea makers ferment the tea leaves. The taste of the tea differs depending on how it is made. I think good taste is the product of passionate hours.

When the tea is ready, tea lovers get together for teatime! For the tea table, one must prepare a teapot, teacups, tea leaves, hot water, and some snacks – and do not forget flowers for decoration! The flowers on the tea table are called dahwa (다화). In a moment, I will introduce the artist who makes dahwa with plum blossoms and beeswax.

To any visitor to Gwangju, I would love to recommend walking along the streets of Yangnim-dong after visiting the historical sites of Gwangju’s May 18 Uprising. In Yangnim-dong, you will see some Korean traditional houses and a few Dutch-style buildings built over 100 years ago by Western missionaries living in the Yangnim-dong area. Walking along the alleys of Yangnim-dong, you can also find adorable small cafes. This is how I came across the cafe Yunhoemae.

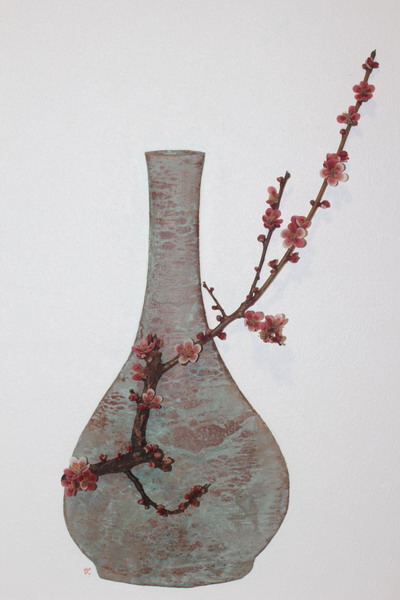

Passing through the small garden, I could hear classical music from the cafe’s large speakers. The cafe had several traditional Korean beverages on its menu. As a tea lover, I ordered green tea. While drinking the tea, I looked around the café and noticed some artworks hung on the wall. Inside the frame of one, an artificial twig with plum blossoms was placed in a relief vase. I thought the artworks went well with the tea and the music. The owner of the cafe said that her husband was the artist. It just so happens that the following year I came across his works at the Gwangju Art Fair.

We are now going to explore tea as well as the accompanying beeswax plum blossoms called “yunhoe-mae.” The artist, Kim Chang-deok (김창덕), who goes by his artistic name Da-eum (다음), spends most of his time these days in his studio preparing for an upcoming exhibition. Though he was busy, he happily made time for this interview about him, plum blossoms, beeswax, and tea.

Jennis: Thank you for making time for this interview. I learned your beeswax plum blossom works are called yunhoe-mae (윤회매). Could you tell me what it means?

Da-eum: As you know, yunhoe (윤회) means “reincarnation,” and mae (매) means “plum blossoms.” In Buddhist terms, yunhoe is samsara, the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. The wax plum blossoms are made by the rebirth process. Bees get honey and wax from flowers, and people make plum blossoms with the wax. So, the beeswax from flowers goes back to being flowers. That is the meaning of yunhoe-mae: plum blossoms reincarnated.

Jennis: It is awesome! What is the origin of yunhoe-mae? Do you know who started to make it?

Da-eum: It was first made by the scholar named Lee Deok-moo (1741–1793) during King Jeongjo’s reign of the Joseon Dynasty. The Joseon Dynasty was a society controlled by Confucian discipline, and the children who were not born from the first wife could not be government officials. However, Jeongjo, the 22nd king of Joseon, implemented an unconventional policy to give official posts to competent people regardless of family prestige. That is how Lee Duk-moo was able to obtain government posts. He was also a scholar, a poet, and an artist who appreciated tea.

Early in the spring, Lee Deok-moo enjoyed having tea along with the scent of plum blossoms. He might float a plum blossom petal on his cup of tea as he gazed at fresh plum blossoms in a vase. But plum blossoms bloom for only a few days of the year. There is a saying in Korean, hwa-moo-sip-il-hong (화무십일홍), which means “No matter how beautiful a flower is, it can’t last for more than ten days.” Its inner meaning is “Beauty or power can’t last forever.” But Lee Deok-moo, the tea-loving scholar, was able to make long-lasting, artificial plum blossoms with beeswax.

Jennis: How did you come across Lee Deok-moo and the yunhoe-mae?

Da-eum: I have read a lot of books related to tea because I like to drink tea so much. I learned that this scholar made artificial flowers to enjoy during his teatime. Lee Deok-moo wrote many books in his lifetime. His last books were published by his son after he passed away. The name of the book series is Cheongjanggwan-jeonseo (청장관전서). Lee’s penname was Cheongjanggwan, and he recorded the lives of the figures of his time in the 71 volumes that made up this series. The set of books is like an encyclopedia. In Volume 33, Lee described how to make beeswax plum blossoms with a detailed description and accompanying drawings. But sadly, the original volumes are kept in the East Asian Library at the University of California, Berkeley, now. After reading copies of Lee Duk-moo’s books, I came to respect him and his life as a scholar. I learned the basics of yunhoe-mae from my master, Buddhist monk Jigwang

(지광스님), who was designated as a human cultural asset for his skills in making traditional paper flowers (jihwa, 지화).

Jennis: Could you tell me how to make yunhoe-mae?

Da-eum: Boil the beeswax and cool it down to about 75 degrees Celsius. I am able to sense the proper temperature with my fingertips. Scoop up a little beeswax with a small, spoon-shaped, petal-making tool and allow it to dry into a thin petal resembling the seed coat of a bean. Make five of these petals and combine them into a single plum blossom. The stamens and pistil are made of roe hair. About 45–47 strands of roe hair are bound together with wax, and the one end is coated with a yellow powder to resemble pollen. After making a sprig of plum blossoms, I create a vase in low relief to go with the plum blossoms and complete the art piece.

Jennis: It is interesting that the beeswax blossoms are artificial, but all the materials that make them are natural.

Da-eum: Right. They are all part of an integrated cycle, like yunhoe-mae.

Jennis: Do you have any plan for your artworks in the future?

Da-eum: I hope that many people can enjoy yunhoe-mae, and I hope that UC Berkeley will return Lee’s original Cheongjanggwan-jeonseo to Korea someday.

Jennis: I hope so, too. Thank you, Artist Da-eum, for your time. I have learned so much, and I hope that all your wishes come true.

THE ARTIST’S PROFILE

Da-eum (Kim Chang-deok) majored in the art history of Buddhism at Dongkuk University. He was once a Buddhist monk and learned beompae, the Buddhist music used in Buddhist rituals, as well as jihwa (지화), from the Buddhist master, Jigwang. He is also talented in writing Chinese-character calligraphy. He has named his artworks yunhoe-dojahwa (윤회도자화, transmigration of ceramics and blossoms). He does sanding on relief pottery and paints on it in various ways. He sometimes includes in his pottery-making process a Bara dance performance, which is also used in Buddhist rituals.

DA-EUM’S MAJOR EXHIBITIONS

Gwangju International Art Festival (2019), Hwaum-sa Individual Exhibition (2018), Triennale di Milano Open Exhibition (Italy, 2015), National Museum of Korea’s Cheong-hwa Exhibition (2015), Gwangju International Art Festival (2013), Exchange Exhibition (Gagosima, Japan, 2013), Gwangju Design Biennale (2009), Exhibition at British Museum and UN Headquarters, (United Kingdom and New York, 2007), Korea–Venezuela Diplomatic Performance (Caracas, Venezuela, 2005), Korean Modern Art Hamburg Exhibition Performance (Germany, 1995), Folk Art Festival (Los Angeles, USA, 1990)

Yunhoemae Cultural Center & Cafe (윤회매문화관 찻집)

Address: 21-2 Seoseopyeong-gil (199 Yangnim-dong), Nam-gu, Gwangju

Hours: 11:30 a.m. – 10:00 p.m. daily

Phone: (062) 375-3397

The Author/Interviewer

Kang Jennis Hyun-suk is a freelance interpreter who loves to read books and grow greens. She has lived in Gwangju all her life and is certainly a lover of the City of Light.