Minhwa, Painting the Peoples’ Desires

By Kang Jennis Hyun-suk.

When the new year comes around, we make resolutions hoping for our lives to be happy. Are you still keeping your New Year’s resolutions? Fortunately, you can have a second chance in Korea with the Lunar New Year, which comes in February this year. In Korea, parents and children, husbands and wives, and brothers and sisters kneel and bow to each other while giving mutual words of blessing for the coming year.

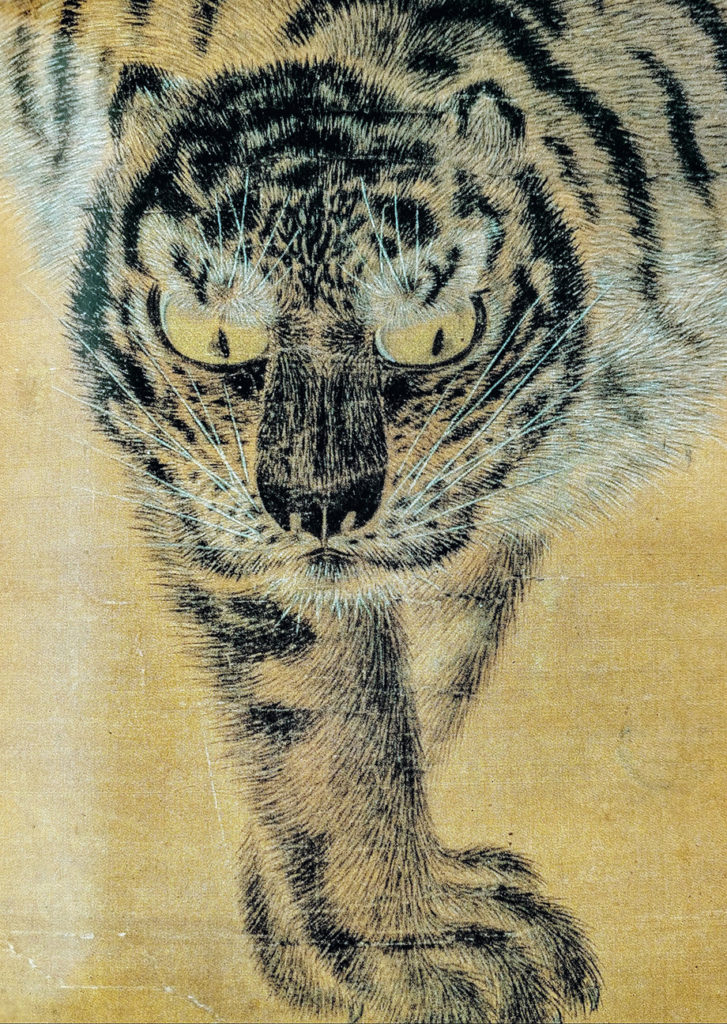

In the old days, there was an additional New Year’s custom. People exchanged paintings of happiness with each other. They put the paintings on the walls in their homes or on the doors to bring them good luck for the year. In particular, putting up a painting of a tiger was believed to repel bad energy. These paintings were called sehwa (세화, New Year’s painting). Sehwa is one sub-genre of folk paintings known as minhwa (민화, literally, folk + painting). We still exchange New Year’s calendars with wonderful traditional paintings on them when the New Year comes. I think this is likely a modern-day manifestation of our ancestors exchanging of sehwa.

What Are Minhwa Paintings?

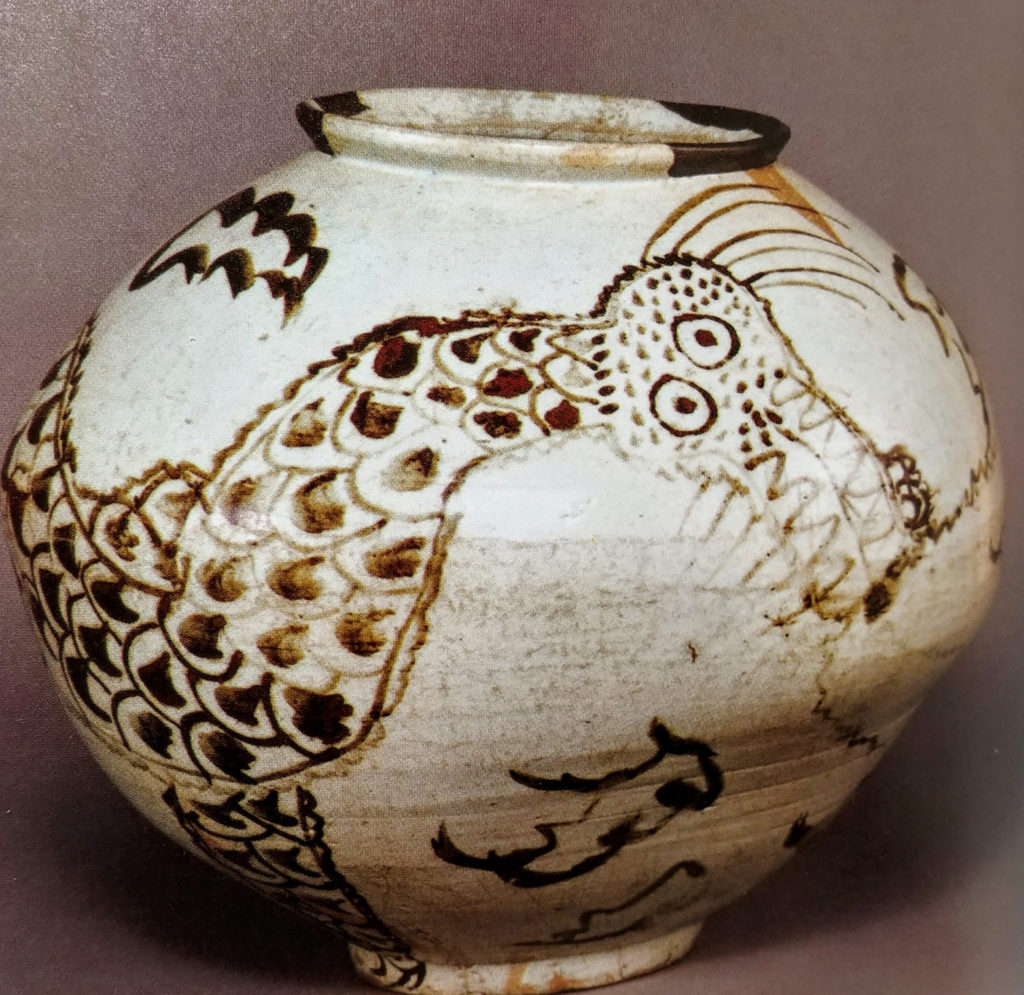

Minhwa are free-style, informal folk paintings resembling the Egyptian murals or the Goguryeo Dynasty (37 B.C. – 668 A.D.) murals. Minhwa contains the essential consciousness and spirit of nature. Many of them have two-dimensional configurations. People enjoyed minhwa throughout their daily lives. On doors, walls, folding screens, ceramics, and even mats, the patterns of minhwa contain the people’s hopes and desires. For example, peaches symbolize immortality, pomegranates and watermelons represent prosperity for one’s offspring, leopards denote bravery, and deer and rocks signify longevity. Different minhwa painting types are named after the symbols they contain.

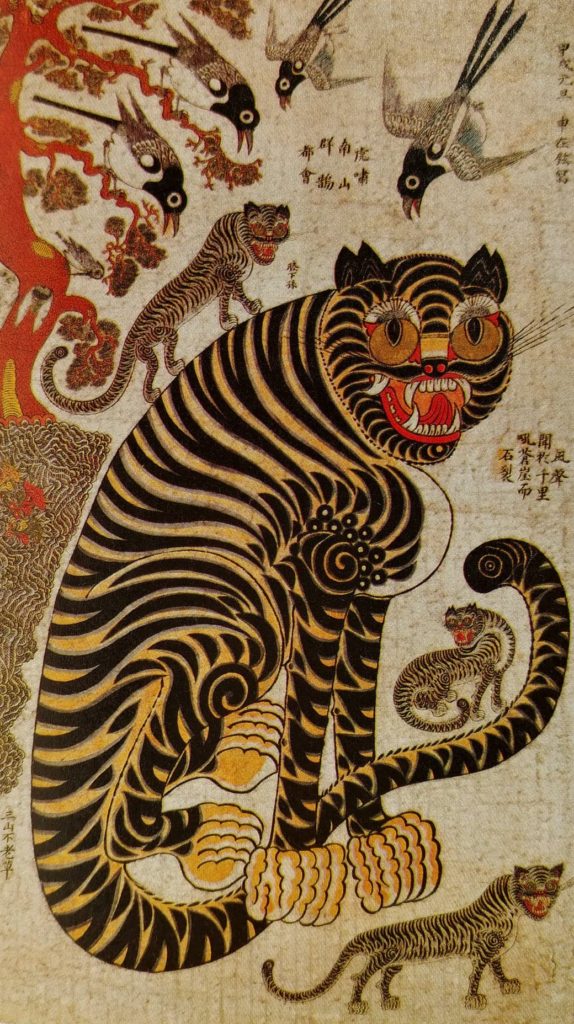

— Hojak-do (호작도, tiger and magpie paintings)

These paintings were made in the hope of bringing good fortune in the new year. Korea was a country of tigers. Two-thirds of the land area are mountains, a favorable habitat for tigers. And there were certainly many stories about the Korean tiger. One of them is “Gotgam and the Tiger.” As the story goes, once upon a time, a hungry tiger came down to a village and sat in front of a hut where a baby was crying. The tiger could hear an old lady’s voice from the hut. She told the baby, “Stop crying or the tiger will come and eat you up! The tiger was surprised. “How does she know I am here?” he thought. But the child did not stop crying. The old lady next told the baby to stop crying because Gotgam was coming, and the infant suddenly stopped crying. The tiger’s pride was hurt. “How frightening Gotgam must be!” the tiger thought to himself. “Scarier than me!” and he ran away so fast that he lost his tail! (The tiger did not know that gotgam is “dried persimmon” in Korean.)

This was only one of the many tiger stories that my grandmother told me when I was young. However, there are no longer tigers living in Korea’s mountains. The Japanese hired hunters and killed off all the tigers in Korea during the Japanese colonial period (1910~1945). The last official record was that of a male tiger captured in October 1921. Now, we can see the tigers of the Joseon Dynasty period only through minhwa folk paintings.

The people of old believed that the evil spirits would run off when they saw the tiger paintings. So, in the new year, people would put the tiger paintings on their walls or on their doors. At first, the minhwa tigers looked brave and scary, but gradually the paintings became simple and more comical. They depicted a mother tiger with long eyelashes, a male tiger with a shy tail, or a tiger smoking a long-stemmed pipe. According to one popular interpretation, these ridiculous tiger images symbolized the corrupted power of the late Joseon Dynasty, and the magpies chirping above the tiger represented the common folk scolding the corrupt officialdom.

— Sip-jangsaeng-do (십장생도, ten longevity symbol paintings)

Represented in sip-jangsaeng-do are ten objects that were thought to symbolize longevity: the sun, clouds, rocks, water, pine trees, bamboo, cranes, deer, turtles, and bullo-cho (불로초, the herbal fungus of eternal youth). These were originally objects of nature worship and were also depicted in murals of Goguryeo Dynasty royal tombs. They were also present in poetry, paintings, and sculptures of this period. During the Joseon Dynasty, sip-jangsaeng paintings were made into folding screens, and they were hung in the royal palaces to celebrate the New Year. The paintings were also loved by the general public later, and they were even embroidered on pillow covers.

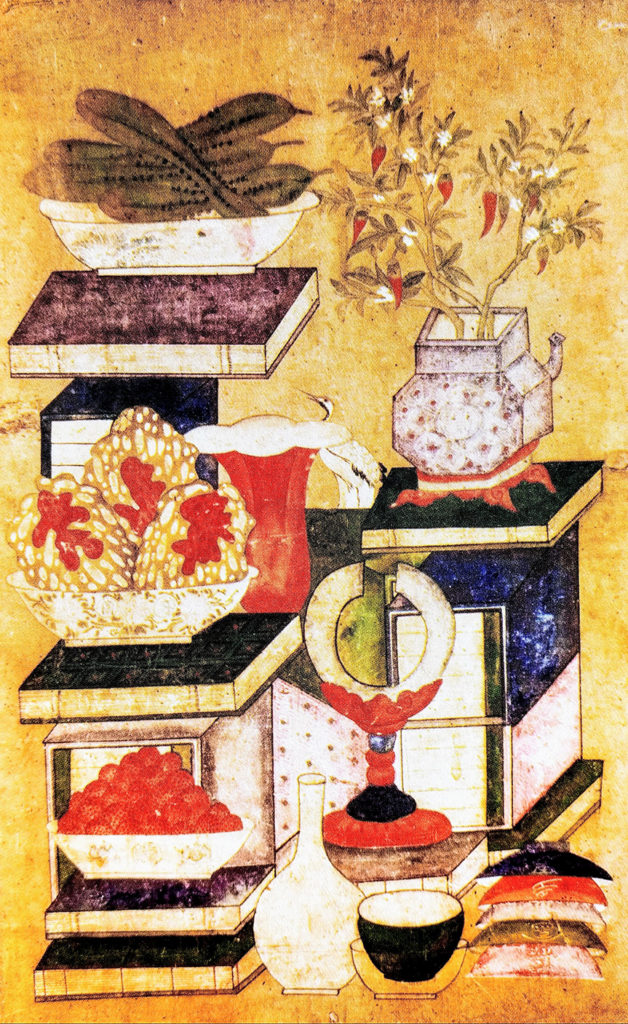

— Chaekgeori-do (책거리도, still-life bookshelf paintings)

There are two kinds of chaekgeori paintings. One is paintings of books on bookshelves and the other is of diverse still-life objects that may or may not include bookshelves. The paintings of bookcases are called chaekga-do. King Jeong-jo (1752–1800) of the Joseon Dynasty was such a book lover that he had a chaekga-do screen placed behind his throne rather than the conventional ilwol-obong-do (sun, moon, and five peaks painting) screen, which symbolized the king. Following the king’s lead, his officials also put the chaekga-do screens in their homes. We can determine what was popular in olden times through the items depicted in chaekgeori-do.

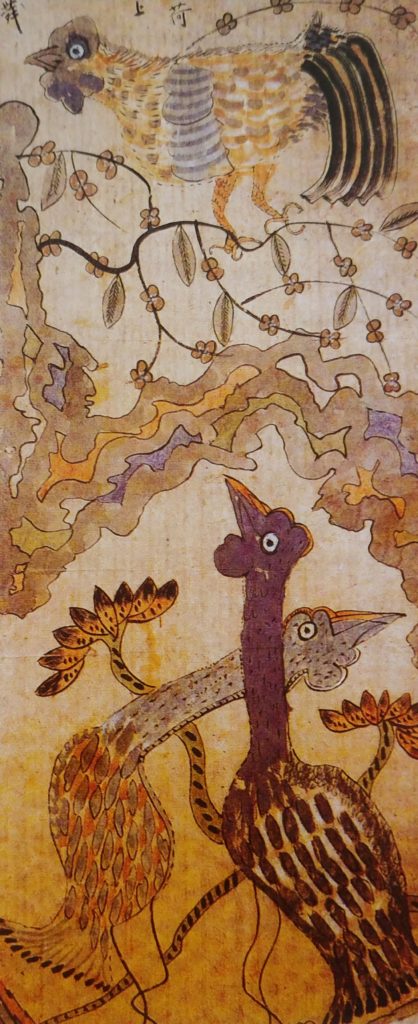

— Hwajo-do (화조도, flower and bird paintings)

The upper class in Goryeo Dynasty times and those who studied Confucian texts in the Joseon Dynasty are called sadaebu (사대부, gentry). If chaekgeori-do were to be found in the sadaebu master’s study, hwajo-do were found in the room of the lady of the home. These paintings contained flowering branches projecting from a vase containing the water of life, an abundance of flowers blooming, and playful birds and butterflies. Hwajo-do of a pair of birds sitting on a branch represented wishes for a couple’s happy life. These paintings were also often made into folding screens to decorate the rooms of the lady of the house.

— Unnyong-do (운룡도, cloud and dragon paintings)

The god of water, the dragon, was believed to rule the seas and bring rain. Fishermen prayed to the Dragon King for a safe return before setting out on a fishing trip. Farmers also held rain rituals by painting dragons on banners during periods of drought. Potters drew dragons on their pottery, too. Just as with tiger paintings, the dragons in unnyong-do also transformed into humorous depictions in the late Joseon Period.

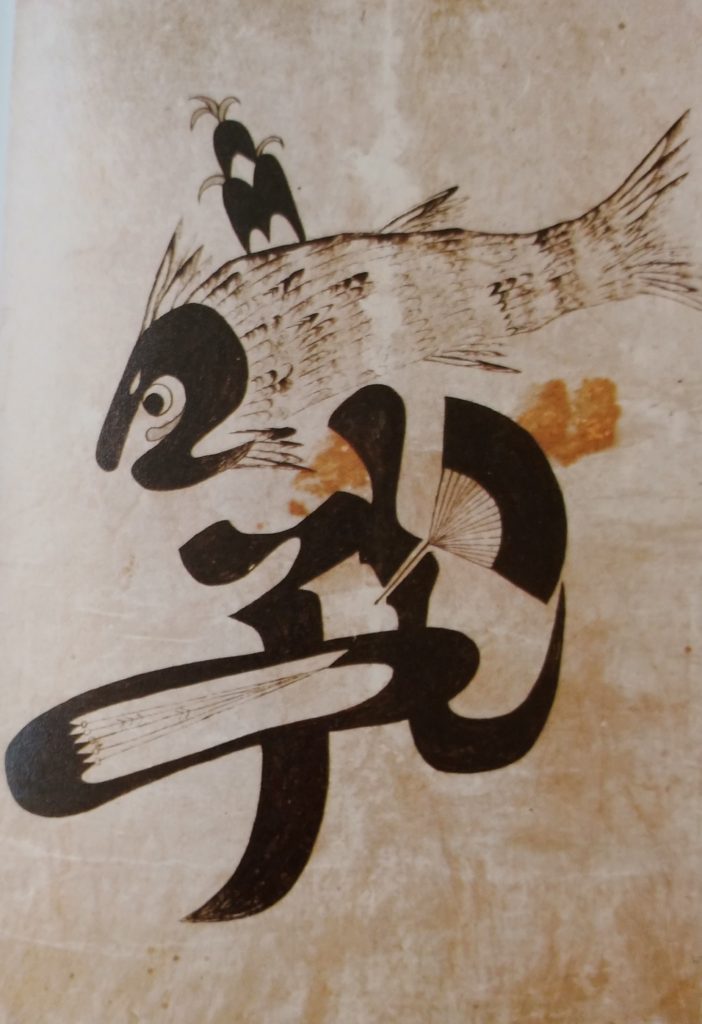

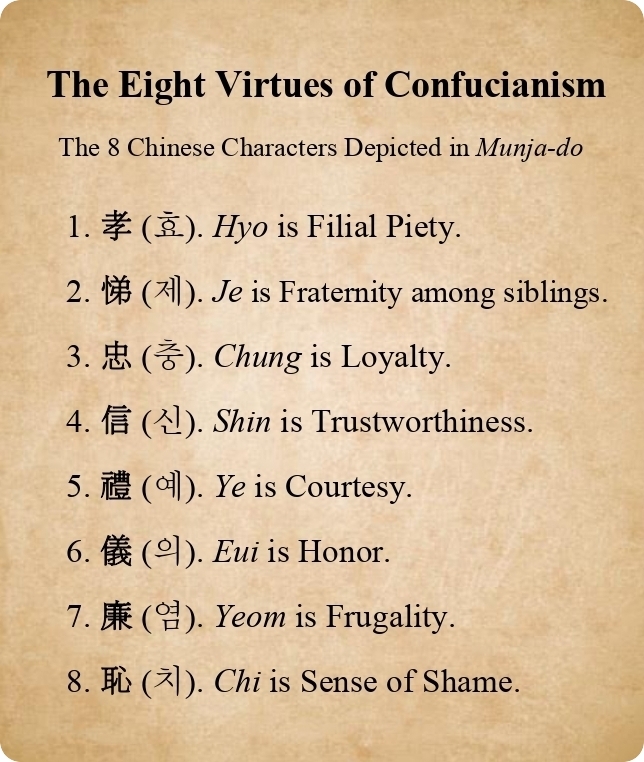

— Munja-do (문자도, Chinese character paintings)

Munja-do are paintings containing stylized, artistic Chinese characters. They contain the characters representing the virtues of Confucianism, as the Joseon Dynasty was built on Confusion ideology. Children of the upper class were able to study the Confucian virtues at seodang, small private schools. However, the common people could learn these virtues through munja-do without knowing how to read Chinese characters.

As an example of munja-do, the Chinese character 孝 (효, hyo) means filial piety. It is the first of the eight virtues of Confucianism. (For all eight, see the accompanying graphic.) One of the many stories about hyo is that of a son from the Jin Dynasty of China who broke the pond ice in the middle of winter and caught a carp for his sick mother. She ate it and was cured! Another is about a man who got bamboo shoots in winter for his mother for the same reason. This is why carp and bamboo shoots appear in munja-do with the Chinese character hyo representing filial piety. Similarly, the other seven Confucian virtues have stories that go with them and symbols that appear with the corresponding Chinese character in their munja-do paintings.

The Origin of Minhwa

When did minhwa paintings first appear? According to records of the early Joseon Period, the royal court artists produced the sehwa (New Year’s greeting paintings) three months in advance and offered them to the king in the last month of the year, and the king gave the sehwa to the officials and the royal family as New Year’s gifts. But before the Joseon Dynasty, the poem describing the “ten long-life objects” was written by Goryeo Dynasty scholar Yi Saek.

It is often thought that folk paintings were painted by unknown artists with no professional training who just imitated the “orthodox” paintings of established artists. However, Kang Woo-bang, an art historian who has worked with Korean art at the National Museum of Korea, found folk paintings in ancient sculptures. He said that minhwa is the root of Korean painting history. This appears to be at odds with the definition of minhwa proposed by Yanagi Mineyosi, who was a Japanese art collector. Yanagi coined the name “minhwa” for Korean folk paintings. The Chinese character for min (民) means “ordinary folks” and hwa (畵) means “paintings.” Yanagi insisted that minhwa as a genre began in the late Joseon Dynasty. Is Yanagi’s naming and description of minhwa proper? As minhwa is getting greater attention from many people these days, the definition and the naming of our traditional folk painting genre deserves further discussion.

Who Paints Minhwa Today?

— Artist Kim Saeng-soo (김생수)

The Jeolla Provinces is the place where traditional Korean paintings and calligraphy using only black ink are more deeply rooted than other regions. So, there was little space for folk paintings. Kim Saeng-soo started painting in his 20s and operated an art gallery in Itaewon, Seoul, while continuing his painting and exporting folk paintings. His father was also a calligrapher, and he used to draw a tiger and place it on the wall when the younger Kim returned from a long trip. His father believed the tiger would fight off bad energy (i.e., evil spirits). In this way, the younger Kim grew up under the influence of folk paintings throughout his life. He came to Gwangju almost 20 years ago and operates the Woocheong Museum of Art in downtown Gwangju. Kim said that he wanted to give chances to the younger generation to encounter Korean folk paintings and has been instrumental in forming the Gwangju Traditional Folk Painting Association. Kim has held the folk paintings exhibition from eastern to western Korea and has also participated in the Korean and German Art Exchange Exhibition at the Asia Culture Center. Kim points out the limitations of the term minhwa. Therefore, he gives lectures under the title of “Traditional Color Paintings.” To carry on the tradition, several of Kim’s students teach folk painting at cultural centers in Gwangju. In commemoration of his 70th birthday, Kim will be holding a mid-March exhibition at Mudeung Gallery.

— Artist Sung Hye-sook

Sung Hye-sook, a calligrapher, grew up in Ulsan and came to Gwangju to learn traditional black-ink calligraphy. There she met her husband, also a calligrapher, and settled in Gwangju. At first, she started making pottery as a hobby. But when she drew traditional patterns on the pottery, she fell in love with them. She found that the patterns she was drawing were of minhwa style. That is how she entered the path to minhwa. She went to Seoul and Incheon to learn from the best experts on folk paintings. She studied minhwa passionately and held her first exhibition at Mudeung Gallery in Gwangju three years after beginning her minhwa studies.

Sung was honored to have the director of the Gahoe Museum of Art, Yoon Yeol-soo, write an endorsement for her first exhibition. Later, she won the grand prize in an art competition held in Cheongju and is a member of the Minsu-hoe, a group of prize-winners in major competitions. These days, she is teaching art students and hopes that her efforts will soon bear fruit. Transitioning from calligraphy to ceramics and from ceramics to minhwa in such a short period of time, she is now one of Korea’s top minhwa artists. During my interview with Sung, it was quite easy to recognize her passion for traditional Korean art.

In Conclusion

It is a pity that there is so much more to say about minhwa that I cannot write here. I have recently read a dozen books on minhwa and was surprised by the diversity and depth of our folk paintings. It has been a great honor for me to be able to conduct interviews with Kim Saeng-soo and Sung Hye-sook, the two great pillars of Gwangju minhwa. I would also like to thank Chung Byeong-mo, a professor at Gyeongju University, for allowing the Gwangju News to use his photos.

Photographs of Sung Hye-sook’s and Kim Saeng-soo’s works by Kang Hyun-suk, courtesy of Sung Hye-sook and Kim Saeng-soo, respectively, from their catalogues.

Photographs of other minhwa works by Kang Hyun-suk, courtesy of Chung Byeong-mo from his book Folk Painting: The Revolt of Unnamed Artists.

The Author

Kang Jennis Hyun-suk is a freelance interpreter who loves to read books. History is particularly one of her favorite topics. She enjoys making new artist friends through writing this “People in the Arts” series for the Gwangju News. Email: speer@naver.com