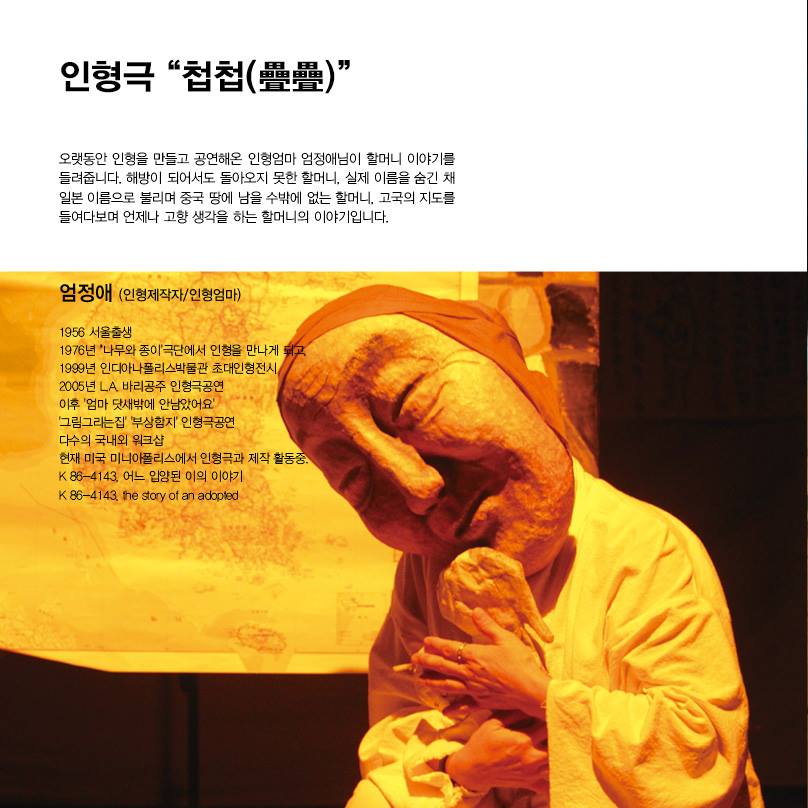

The Mother of Puppets

Ms. Um Jeong-ae.

Interview by Jennis Kang.

I was sitting in a cafe waiting for a friend, when I noticed a woman in a black fedora walking past the window. She looked familiar to me; I tried to remember where I’d met her. I suddenly realized she was my Facebook friend, Ms. Um Jung-ae, known as the “Mother of Puppets.” “What’s going on,” I thought, “She should be in the States!” I popped out to say hello, as I was a big fan of hers. Our first chance encounter was last spring, and this spring, she came to Gwangju again to undertake a big project. So, to introduce Ms. Um, the Mother of Puppets, to the readers of the Gwangju News, I arranged with Ms. Um the following interview.

Jennis Kang: Hi, Ms. Um. I’m glad to see you here again. Can I ask what brought you to Gwangju to do volunteer work?

Um Jeong-ae: Hello, I’m happy to be in Gwangju again. Actually, for decades, I’ve felt that I owe something to the citizens of Gwangju. When the Gwangju Uprising broke out, I was abroad. One day, one of my coworkers showed me an article in a newspaper and said, “This tragic news is about your country. I’m really sorry.” When I read the newspaper article, I couldn’t believe it. The photos in the paper were so shocking and horrific that I even thought this had to be fake news. The heartbreaking news and the photos were indelibly imprinted on my mind. I was so sad.

When I came back to Seoul later that year, the people of Seoul didn’t know what had really happened in Gwangju. They didn’t believe me when I told them what I’d read in the newspaper because the military government had suppressed all the news about the May 18 uprising. We were kept in the dark for years. Gwangju had been isolated from the rest of the people of Korea for decades. I felt really sorry for Gwangju citizens, and I wished I could give something as a consolation and to share their sorrows.

Kang: As a Gwangju citizen, I appreciate your kindness. I heard that you’ve come to Gwangju to do a project to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the May 18 Gwangju Uprising. Would you tell me about it?

Um: Yes, this year was the 40th anniversary of May 18. So, some of the artists of Gwangju, the youth of the YMCA, and the Mothers of May Victims (the victims included many young people in their teens and twenties, so their mothers are still alive) are making big paper puppets in memory of May 18 victims and to preserve their spirit of democracy. Actually, we planned to parade down the historic Geumnam-ro wearing these puppets. But because of the COVID-19 situation, the ceremony was canceled. So, instead of parade, we’re making a short film about this project.

Kang: I’m sorry we missed the big puppet parade, but I understand our health and safety should have priority above all else. I heard that people call you the “Mother of Puppets.” How did that come about?

Um: I ran a business in Seoul when I was in my forties, and I sponsored a few artists at that time. One of those artists made paper puppets. Sometimes I dropped by her place and learned how to make puppets from her. Actually, I’d once put on a puppet show with my friends when I was an undergraduate. Going further back, I loved to talk with my dolls as a child, since I was often alone as my mother was a working mom.

Kang: So that means your life with puppets started quite a long time ago. But we don’t usually call people who love puppets the “Mother of Puppets.” There must be more to your story of puppets than that.

Um: Yes, one day a friend of mine asked me to lend some space for young women to stay. They were adopted as Korean children to live in other countries, and they were visiting their motherland in search of their birth mothers. I had a space for them to stay. They were five girls from Europe and the U.S. Their stories had been in the newspapers. Luckily, four of them found their birth mothers. But one girl from the States was adopted so young that she had no memories of her birth mother. When the girl was going back to the states, I felt so sorry for her. So, I made her some paper dolls and told her, “Don’t forget there’s someone in your motherland who wishes your well.” I think that it was from that time that people began to call me the “Mother of Puppets.”

Kang: Wow, what a sad but heartwarming story! You said that you’d lived in Seoul, but now you live in the States. Would you tell me how you came to move to the United States?

Um: When the adopted girl went back to the U.S. with my dolls, people around her – especially one who worked at a museum – asked her how she’d gotten the dolls. They loved the dolls with Korean facial features. She told her story to the art director, and the fascinated director contacted me to exhibit my dolls in his museum. At the time, my business had just been struck by the IMF during the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997. So, it was easy to fly to the States, where I ended up exhibiting my dolls at several museums. There I met some puppet actors that I associated with and my husband, too.

Kang: I love the saying “When God closes a door, He opens a window.” Your story reminds me of that saying. So, you changed your life from that of a business person to an activist. I heard you’ve been working as a green and human rights activist with your large paper puppets. I saw the big puppet parade for the Sewol ferry victims in Minneapolis. I think that these puppets have the power to allow people to deal with serious issues in a non-confrontational manner. And for yourself, what do you think a puppet is?

Um: I think making puppets is like doing Zen for me. That Zen is letting us feel free from distraction or weariness. By attaching little pieces of glued paper over and over and over to each other, making paper puppets leads me into a world of vacancy. I feel free from endless thought. It provides me with the opportunity to take an objective view of myself. And I think the puppets I make are another me. Playing and talking with the puppets makes us meet ourselves and reconcile the two, I think.

Kang: So that’s why you call it “paper Zen.” I hope many people can have the “paper Zen” experience with you while you’re staying in Gwangju. Thank you for sharing your story with us. I hope you feel at home during your stay in Gwangju.

Kang: [After the May 16 puppet parade] The parade, with its huge national flag and giant puppets, was amazing as it wound through the streets of Gwangju. What was the most impressive moment for you during this two-month puppet project?

Um: There are many: the young artists of Gwangju, students, fathers and children, husbands and wives, who all volunteered their time to make the puppets. But the most impressive was a call after the parade from a mother of May, who lost her husband in the May 18 Uprising. She said that I gave her a chance to walk with her husband again. She felt like her husband came alive during the parade. I hope it helped her relieve some of her pain.

Kang: Thank you, Ms. Um. You gave us the opportunity to look back and overcome our painful sadness through the making of puppets and the parade. The parade reminds us that we are still on the way to fully healing from May 18.

Photographs by Choo Hyun Kyung, Jennis Kang, and David Shaffer.

THE INTERVIEWER

Jennis Kang is a freelance English tutor and once-in-a-decade interpreter. She worked for the Asia Culture Center during its opening season. She likes to grow greens and walk her dog. And sometimes she reads; Roald Dahl’s works are her favorites.