The Korean Diaspora of the Americas and the Provisional ROK Government

By Kim Jaegi

The Beginnings

The history of the Korean diaspora in the Americas begins with the immigrant laborers to Hawaii in 1903. Two years later, approximately 7,400 Koreans had arrived to toil on sugar plantations. In 1905, 1,033 Koreans worked on agave farms in Mexico while being pricked by thorns in the scorching sun. In 1921, 288 of the Koreans in Mexico extended the community to the Caribbean Sea, as they ventured to Cuba to work on its sugar plantations and agave farms.

These Koreans without a country all their own established the Korean National Association (KNA) in 1909. It soothed their homesickness and defended their interests. The KNA sought a home for Koreans outside of their lost homes and supported the independence movement by sending funds to the Provisional Government of the Republic of Korea (ROK) in Shanghai.

On February 1, 1909, in San Francisco, Bak Yong-man*, Syngman Rhee*, and An Chang-ho* led the founding of the KNA, which would act as the representative organization for all Koreans in the Americas. National heroes Jang In-hwan* and Jeon Myeong-un* had been stirring enthusiasm among Koreans in America to resist the Japanese Empire, and their acolytes saw the necessity of integrating with the KNA and combining efforts with the Associations in San Francisco and Hawaii. The KNA’s explicit goals were thus: the repeal of the Ulsa Treaty [which made Korea a protectorate of Japan and was a precursor to annexation in 1910]; the restoration of Korea’s statehood; and the peace and prosperity of overseas Koreans.

From the Hawaiian Islands to Mexico and Cuba, the small group of immigrant Koreans banded together tightly through the KNA. In 1910, as Korea lost its last bit of autonomy, the KNA served as an ersatz government for the now-stateless overseas Koreans.

Linking Korean Patriots

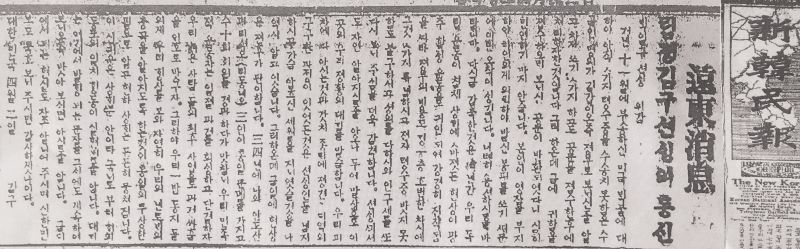

The KNA became the mouthpiece of the Korean community through printing The New Korea (신한민보) newspaper. It gave hope to the long-suffering Koreans and kept alive the dream of political independence. The New Korea became a mainstay for the Koreans of the Americas through all stages of life, in times both happy and sad. Koreans in Asia and in the Americas also established lines of communication that linked Koreans in different countries with general news, the announcement of the second-generation births [American-born children of Korean immigrants], pictures, marriage announcements, and advertisements for ethnic foodstuffs.

The independence movement doggedly brought news of events in the colonized fatherland as well as in Manchuria and the maritime regions to the overseas Korean community, thereby keeping the spirit of independence alive. The paper reported on support and donated funds for the March 1st (1919) Movement and its “echo” a decade later in the Gwangju Student Independence Movement. Even the Koreans in Mexico and Cuba, who were in especially dire financial straits, offered aid.

Koreans in the Americas maintained relations with the Provisional Government in Shanghai, continuously giving funds for independence, which we know from a May 1, 1930, article in The New Korea. As news of the Gwangju Student Independence Movement reached the Americas through the KNA, many Koreans responded by donating money to the students through the Provisional Government. Pivotal nationalist Kim Gu* expressed his gratitude in a letter to The New Korea, thanking KNA members for their immense financial help to the Provisional Government.

For the past 90 years, Kim Gu’s letter was largely unknown.

For the past 90 years, Kim Gu’s letter was largely unknown. When I was in New York for the 2016 academic year, my studies on the Gwangju Student Independence Movement led me to come across The New Korea. I then found Kim Gu’s letter mentioning the Independence Movement, and then confirmed it as being delivered to the then-chair of the KNA, Baek Il-gyu* (“Earl K. Paik”).

The Gwangju Student Independence Movement Stokes the Fires of Patriotism

This letter is an invaluable resource considering Kim Gu made no other mention of the Independence Movement in his diary or in the twelve volumes of collected writings discovered in 1999. This letter, written on April 2, 1930, and brought by sea from Shanghai to San Francisco appeared on page 3 of The New Korea on May 1. The letter reads:

The independence movement, yet again cut down and languishing for several years, has been strongly reinvigorated by the Gwangju Student Independence Movement. In response, your [KNA members’] sincere outpouring of support to help the [Provisional] Government at a time of immense costs, without even a note of receipt and regardless of credit, is a deeply moving act that I wish to commemorate.

This letter, reproduced in The New Korea, not only shows Kim Gu of the Provisional Government in Shanghai directly citing and praising the Gwangju Student Independence Movement in print for the first time. It also attests to the continual remittances by the community of Koreans in the Americas for the national independence fund. Also, through this letter, we know that the Korean diaspora of the Western Hemisphere made large donations to the Provisional Government motivated by the Gwangju Student Independence Movement.

In this letter, Kim Gu referred only to the “poll tax” (인구세) that the Koreans of the Americas had all paid. Until now, the known specific references in Kim Gu’s diaries were to people like Kim Gyeong* (“Travis Kim”) in Chicago, who raised money for the Provisional Government to pay rent in Shanghai. The diaries also express gratitude as “$200 was not trivial at the time.” The passages also acknowledge “figures such as Kim Gi-chang * and Lee Jong-o* in Mexico as well as Lim Cheon-taek* and Park Chang-un* in Cuba who supported the Provisional Government.”

Honoring the Worth

The Koreans of the Americas continuously provided substantial support even amidst financial crisis and did so all the way until liberation in 1945. Through these deeds, about 300 persons are in the national registry for acts of valor.

The Koreans of the Americas continuously provided substantial support even amidst financial crisis and did so all the way until liberation in 1945. Through these deeds, about 300 persons are in the national registry for acts of valor. However, their deeds and the official acknowledgement thereof have not reached all descendants. This applies to the progeny of 40 of the 60 Koreans who lived in Mexico and 35 of the 43 in Cuba.

The Covid-19 pandemic stalled efforts to track the descendants of these Koreans in Mexico and Cuba, but I have conducted volunteer visits to Hawaii, Mexico, Cuba, and New York from January to April of this year. I am analyzing roughly 2,000 persons I discovered through photographs taken at Diamond Head Cemetery in Hawaii. Visits to Mexico and Cuba have already resulted in notifying the descendants of honorees like Lee Gi-sam*, Kim Seong-mi*, Lee Don-ui*, Lee Hak-sa*, Roh Deok-hyeon*, Kim Chi-myeong*, Lee Geun-yeong*, Hur Wan*, Kim Yeong-seong*, An Sun-pil*, An Ok-hui*, and Han Ik-gwon* [each of whose descendants can receive special honors].

I estimate roughly 300 people gave support to the KNA and the Provisional Government in their independence efforts but remain unrecognized. Because problems of fairness continue to plague these efforts to bestow posthumous awards to these meritorious Koreans, the [Korean] government needs to take special measures to ensure the proper honoring of these supporters [of Korea’s independence].

*Recipient of honors for national valor.

The Author

Kim Jaigi is a professor of Political Science at Chonnam National University. He is the author or editor of multiple books on national liberation movements, has written several academic articles, and is the chair of KORiaspora, a research project that documents the travails of overseas Koreans from the late-Joseon era to today.

Edited and translated by Jonathan Joseph Chiarella