A Tale of Two Systems

Written by William Urbanski.

Perhaps at some time in your life, you have looked up to the starry cosmos at night and wondered how people can simultaneously be so breathtakingly clever and preposterously daft. How is it that someone with a PhD in physics will forget his car keys? What about a champion chess player who walks smack into a telephone pole because she is not paying attention? At some time or other, we have all made silly mistakes that we are not proud of and leave us wondering what was going through our minds.

Fortunately, the field of psychology has discovered a conceptual framework that can act as an analytical tool to decipher otherwise inexplicable behavior, situations, and phenomena.The idea that the human mind contains two different and sometimes competing cognitive systems is an idea championed by Nobel Prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman. In his book Thinking Fast and Slow, Kahneman details the ingenious reasoning and methods he used to essentially prove his theories.

His conclusion, which is more or less accepted as fact in the academic community, is that the human mind switches between two modes of thinking, aptly named System One and System Two. System One (sometimes referred to as the “intuitive” or “automatic” system) handles everyday, ho-hum responses to various phenomena. Actions carried out by this system are: walking, chatting, putting on a sweater, changing channels on your TV, and removing your hand quickly from a hot stove. The automatic system is extremely useful because it does not tie up our cognitive resources dealing with trivial things, and once it learns basic tasks well enough, it performs them quickly.

That being said, using System One for all daily tasks though is extremely problematic because, when System One encounters a problem it has never faced, it often relies on heuristics (rules of thumb) which can be ineffective or provide sub-optimal results. Many tasks require a different mode of thinking: System Two.

System Two is the rational, reflective system responsible for critical and complex thought processes. To see the difference between the two systems, try this simple experiment: Recite the alphabet from A to Z. Easy, right? Reciting this sequence of letters is a task handled by System One. Now, as quickly as you can, try saying the alphabet backwards from Z to A. Except for the select handful of people in the world who have memorized the alphabet backwards, this sequence should be somewhat difficult because the automatic system simply cannot handle it.

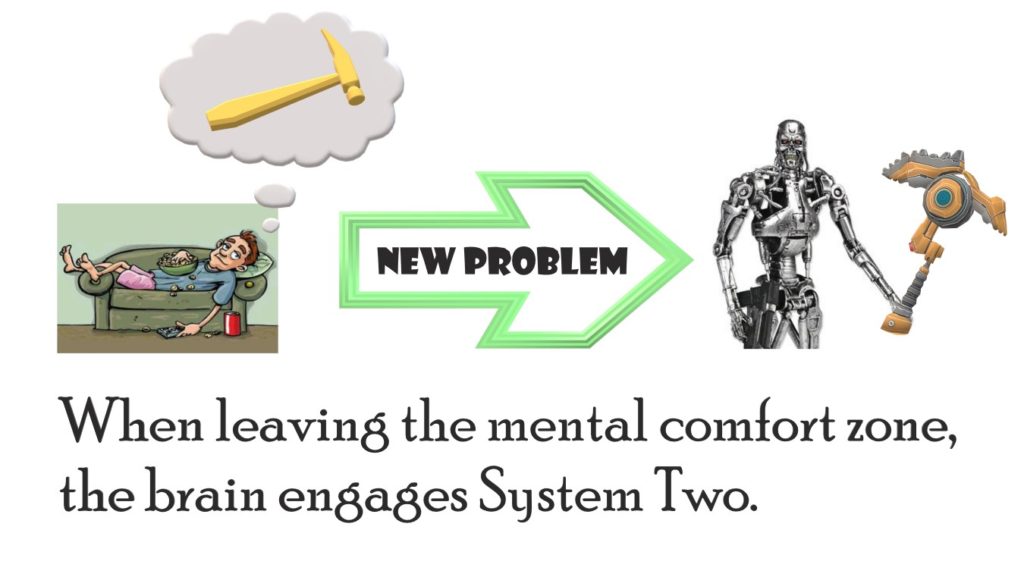

That little stressful feeling you get when you try to do a complex task like this is a sign that System Two is engaged. System Two handles all sorts of stuff, like doing math, but also takes over when it is necessary to exercise self-restraint or during strenuous physical activity. Where System One can be thought of as an impulsive child (or a dirty, lazy hippy), System Two is like a slow, deliberate Terminator (the T-800, not that silly Rev-9 model from Dark Fate).

Using System Two is cognitively expensive and often physically draining, so, not surprisingly, humans actually hate using it and therefore avoid using it whenever possible. As a consequence, often when encountering a problem or situation where System Two should be engaged, people resist activating it and instead rely on System One, which for the above mentioned reasons is ill-equipped for many problems and can lead us to making errors.

So what does that mean for us? The knowledge of dual thought systems allows us to gain greater insight into why certain decisions are made and why people behave in certain ways. Here are some examples.

Big-Box Store’s Decision to Stop Providing Tape and Ribbon to Assemble Boxes

When I first heard that the big-box stores were going to stop providing tape, ribbons, and boxes to customers, I was furious. Although this was done ostensibly to “help the environment,” I could not help but feel this was just a big cost-cutting measure by the greedy CEOs. I mean, how much does it cost the stores to provide tape and ribbon? Well, it turns out, probably a lot.

In his book Predictably Irrational, devised a series of clever experiments that irrefutably proved one simple fact: When something is free, people absolutely lose their collective minds. Getting something for free, in our minds, has no downside, no matter what the item is. This leads to people taking too much tape and ribbon, increasing costs beyond a sustainable level for the stores.

Analysis: System One: Completely engaged. No impulse control.

System Two: Overridden by free stuff!

Otherwise Brilliant Students Struggling to Speak a Foreign Language Fluently (and Falling Asleep in Class)

True fluency involves using System One. When first learning a language, it is necessary to analyze and remember each and every rule, which is unnatural. Students also become completely fatigued and appear bored after about 20 minutes of studying. Analysis: System One: Not available to complete complex tasks.

System Two: Working overtime, causing mental and physical fatigue.

Delivery Drivers Who Drive Their Scooters at High Speeds in the Downtown Gwangju Area on Saturday Nights and Honk Overpowered Horns to Scare Pedestrians Out of the Way

There is not much to say about these lunatic renegades, except that the cognitive dissonance and breathtaking intellectual somersaults used to justify such reckless behavior warrant nothing but the harshest opprobrium and censure. Nobody needs their fried chicken that badly, you maniacs.

Analysis: System One: Malfunctioning.

System Two: Not engaged / Not existent.

Leaving a Door Wide Open in the Middle of Winter

Admittedly, an open door in the middle of winter is a dynamic and multi-faceted problem that can easily overburden even the most sophisticated thinker’s cognitive resources. Like a quantum particle, a door in the middle of winter can exist in multiple states (in this case, open or closed). However, the primary way to distinguish between a door in winter and a quantum particle is that, unlike a quantum particle, a door in winter can only exist in one state at any given time, that is to say, it can only be open or closed. When trying to decide whether a door in winter should be open or closed, one should first determine if it is in fact wintertime or not. This problem in itself is nebulous and often has no binary solution, but there are some guidelines. If it is near zero degrees Celsius, if it is snowing, or if it is between the months of November and March, there is a good chance that it is, in fact, winter. If one can reasonably conclude that it is winter, the proper thing to do is to close the damn door.

Analysis: System One: Overwhelmed by stimuli or perhaps frozen due to the winter temperatures.

System Two: Instead of using System Two to contemplate the virtues of an open door in the middle of winter, System One should, within milliseconds, become engaged and immediately compel the observer to shut the door because heating oil costs money and the building owner is not paying to heat the whole neighborhood.

Conclusions

These systems are not mutually exclusive and in fact work in tandem a lot of the time. What is important to keep in mind is that not only is System One an ineffective tool for many of the complex and novel situations we may encounter in life, but humans also have a natural tendency to resist the critical thought processes handled by System Two. System Two, much like a muscle, can be trained and improved but only through sustained, deliberate use. So get out there and flex your System Two!

THE AUTHOR

William Urbanski, managing editor of the Gwangju News, has an MA in international relations and cultural diplomacy. He is married to a wonderful Korean woman and has myriad interests, but his true passion is eating pizza.