The English of North Korea: Analyzing Kim Jong-un’s Revised English Textbooks

An Interview with Joo Yunha

Through my work at Chonnam National University, the Global Teachers’ University graduate program has brought me into contact with many intriguing academic fields and the brilliant researchers who contribute to them. Any of these scholars would be great to interview, but one recent doctoral graduate by the name of Joo Yunha had a research topic so interesting that I couldn’t resist reaching out to learn more. What follows is our interview concerning her fields of corpus linguistics and English education and how they intersect with North Korea’s revisions to English textbooks during the Kim Jong-un era.

Isaiah Winters (IW): Thank you for making time for this interview. I found your research particularly interesting for its unique analysis of English education materials in North Korea. Can you give Gwangju News readers a general overview of your academic research?

Joo Yunha: My doctoral research involves analyzing secondary school North Korean English textbooks, and my recently finalized dissertation examines the reading passages in North Korea’s current middle school English textbooks. When Kim Jong-un came to power, he announced the 2013 revised curriculum and changed the textbooks accordingly. Therefore, the recent books differ from the previous ones published in the Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il eras, and I have worked to detail those differences in my research.

IW: In order to analyze North Korean English language textbooks, you first have to get your hands on them. How were South Korean scholars like yourself able to get these books, and where are they being kept now?

Joo Yunha: The exact route through which the textbooks entered South Korea has not been disclosed due to national security laws. It is presumed that the books were brought in by Korean-Chinese. Someone who read my thesis and contacted me in the past said that there is a way to obtain North Korean documents or books through Korean-Chinese, but they told me it would take time; also, it comes with risks and costs money.

Actually, Chonnam National University, Yonsei University, and other libraries accepting North Korean books have the textbooks, but only in CD-ROM format. Therefore, even I have never seen the originals. As far as I know, if you want to see the actual books, you have to go to the North Korean Resource Center of the Ministry of Unification. However, even there some of the hard copies are not available. So, if you want to see the textbooks in their entirety, you can only check them out on CD-ROM. Given these limitations, when I was doing my research, I felt that information about North Korean textbooks was not being shared very well.

IW: What were some of the more fascinating additions you noticed in the revised English textbooks, and what do you think these changes suggest about the evolving nature of English education in North Korea?

Joo Yunha: As previously stated, I mainly studied the textbooks of the Kim Jong-un era and compared them to textbooks of the previous eras through a comparative analysis. The revised textbooks I analyzed each consisted of 12 units, in which four units at a time are studied and then reviewed through a revision unit. In addition, each unit now consists of more diverse activities than before the revision. Furthermore, it was observed that the content and format of the textbooks were improved so that learners could more actively participate in class through pair/group activities rather than just by learning individually. A change in the textbook structure leads to a change in the class, which reflects North Korea’s change in perception and student behavior. After careful evaluation, these aspects suggest that North Korea, which has been cut off from the outside world and maintained only internal solidarity, nevertheless, aims for education that meets global trends in English learning.

IW: Conversely, what were some of the things missing from the newer textbooks you analyzed and the possible implications of those changes?

Joo Yunha: In an English as a foreign language (EFL) country like North Korea, opportunities to use English outside of school are limited because the language is not widely used in everyday life. Therefore, classroom English has great significance in North Korea, and the role of textbooks is very important. In the revised textbooks, specific communication-oriented goals related to school and daily life appeared as the main topics of reading passages.

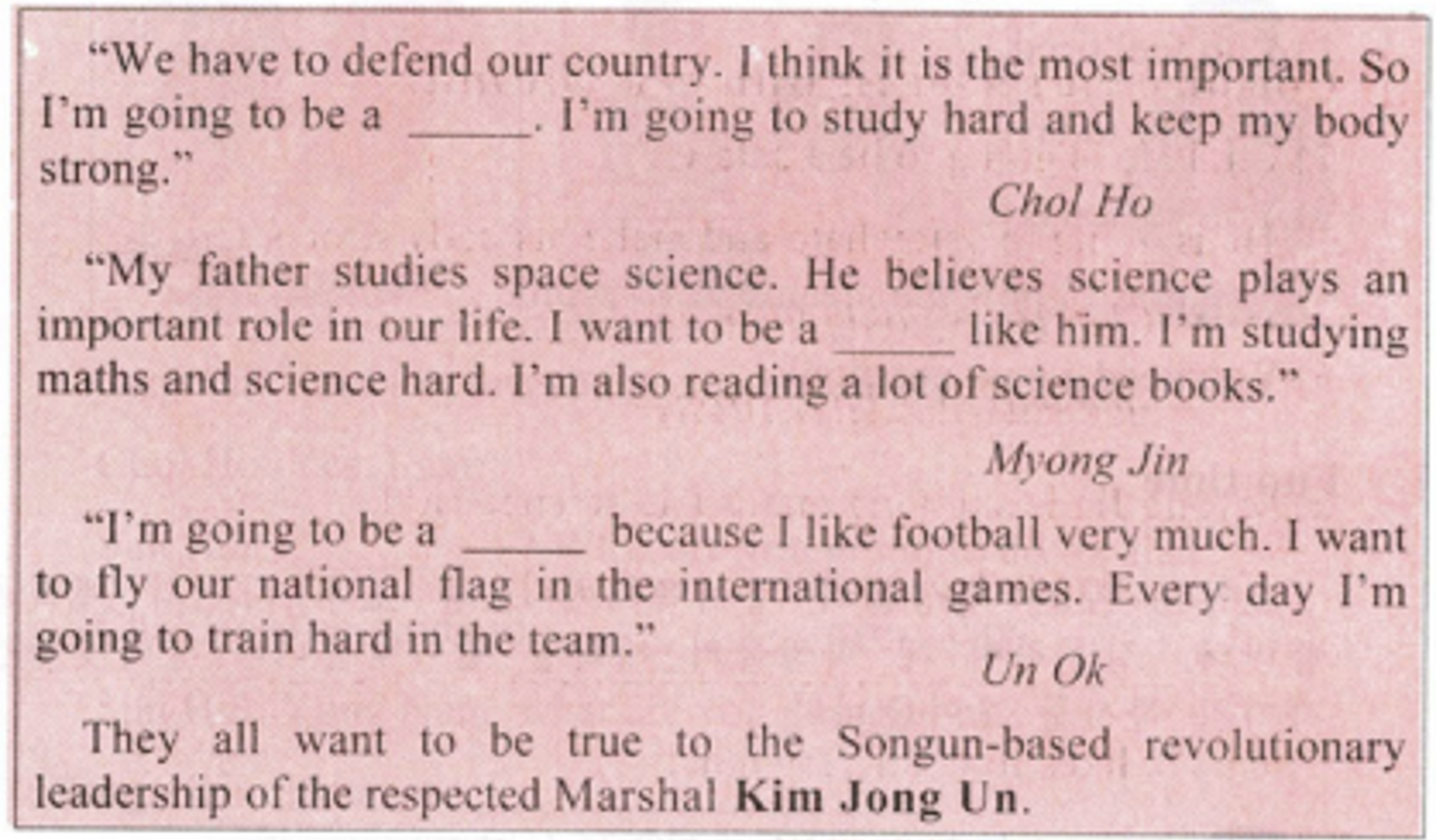

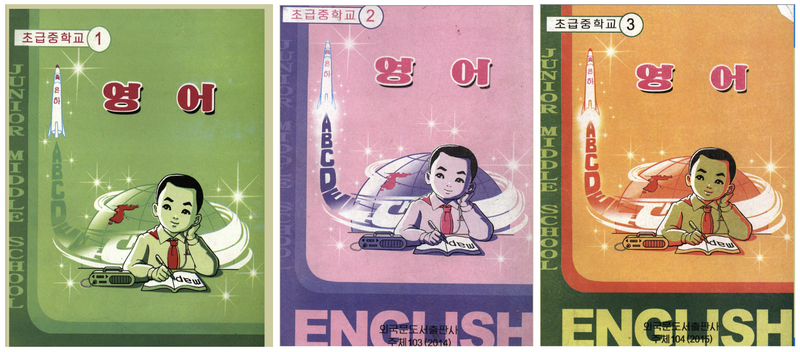

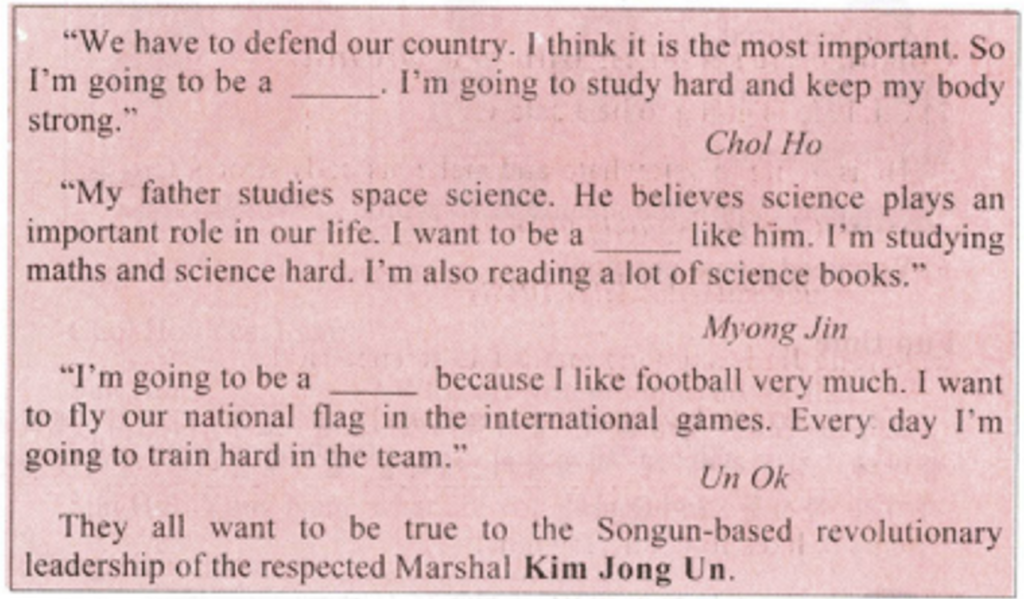

Unlike in the older textbooks, now reading topics including criticisms and distortions of both American imperialism and South Korea, as well as lessons on fables, are not included. This shows that North Korea’s hostility is not revealed through textbooks and that many students are not being infused with it. Despite these alterations in reading passages, my analysis also confirmed that idolization in the texts has remained. This includes idolization of the Kim regime and certain occupations like that of soldier, scientist, and athlete. Idolization is thought to be an inevitable part of communist countries such as North Korea, but it appears less in the revisions compared to the past. Interestingly, one quintessentially North Korean detail that has been retained in the revised texts is the Juche calendar, which begins at 1912 (Juche 1), the birthyear of Kim Il-sung. Thus, revised texts from 2013, 2014, and 2015 appear alongside the respective years of Juche 102, Juche 103, and Juche 104.

IW: Based on the textbooks’ structure, you were able to find out about changes in North Korea’s secondary education structure, in addition to interesting links to the British government. Explain some of these findings for our readers.

Joo Yunha: Before the revision, North Korea operated a six-year secondary school education system. Since the Kim Jong-un regime, however, the school system has been reorganized into three years of junior middle school followed by three years of senior middle school. Junior middle school corresponds to South Korea’s middle school, and senior middle school corresponds to high school. Another major change has been in terms of references. It has long been known that North Korea develops its own English textbooks, and in fact, there was no case in which reference books were specified in the textbooks before. However, in the 2013 revised curriculum, it was specified that books from Cambridge University Press were referenced.

Since the 2000s, North Korea has received UN and Western social support. In particular, the British government has been sending support for educational development to North Korea for the sake of cultural exchange and is playing a leading role in changing the North Korean English education system by passing on English teaching methods. In addition, North Korea has received help from UNICEF to reorganize its English education. With this aid, it received support for a new printing press, improving the quality of existing textbooks and enabling a turning point for compiling revised English textbooks. With this background in mind, it is no surprise that British spelling in North Korean English textbooks can be seen.

IW: Based on your research, what role do you think English plays in North Korean society today? Also, what are the most commonly taught languages in North Korean schools?

Joo Yunha: Before the revision in North Korea, English or Russian were the only languages taught in cities in 2003, but in 2013, English education was expanded nationwide. In the revised curriculum, foreign language subjects were unified into English, and the Russian language course was abruptly ended. As a result, the number of hours spent by students in English classes has been greatly expanded (Cho et al., 2015). Moreover, English subjects are more emphasized than ideological education subjects, which have traditionally been very important. This result highlights North Korea’s very peculiar decision to teach only one foreign language subject throughout a single country, and such a decision shows that North Korea strongly focuses on English today. Also, it can be said that this is a significant change that clearly demonstrates how much competence in English is being strengthened in education across North Korea.

IW: You’ve just completed your PhD in this lesser-known area and are now set to further your research. What topics might you explore going forward as a scholar, and what’s your hope for your field of research?

Joo Yunha: Until now, I have been doing research mainly focused on reading passages at each school level in junior and senior middle school. In a future research project, I plan to further analyze North Korean English textbooks through the learning activities and question types related to these reading passages.

As for future hopes, despite the fact that copies of the 2013 curriculum are in South Korea, they are not widely shared. Therefore, when analyzing textbooks, the interpretation of the curriculum should be better supported, but support in this area is lacking. So, I hope that North Korea’s educational curriculum will be released more freely to the public soon for further research development.

IW: Thanks again for sharing your unique insights, and best of luck in your future academic endeavors!

References/Selected Works

Cho, J. A., Lee. G. D., Kang, H. J., & Jung, C. K. (2015). Education Policy, Education Curriculum, and Textbooks in the Kim Jong-un Era. Seoul: Korea Institute for National Unification.

Joo, Y., & Uhm, C. J. (2022). Analysis of reading passages in North Korean junior middle school English textbooks based on the 2013 Revised Curriculum. In KATE (Ed.), KATE SIG Proceedings. KATE.

Lee, M. H., Kim, Y. H., Choi, K. N., Park, C. R., & Lee, M. I. (2013). Junior middle school English 1. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Lee, Y. C., Kim, W. S., Hwang, C. J., Park, C. R., & Lee, M. I. (2015). Junior middle school English 3. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

Park, C. R., Lee, M. G., Oh, S. H., & Lee, M. I. (2014). Junior middle school English 2. Pyongyang: Foreign Languages Publishing House.

The interviewer, Isaiah Winters, is on the editorial staff of the Gwangju News.

Graphics courtesy of Joo Yunha.

The Interviewee

Joo Yunha received her PhD from the Department of English Education at Chonnam National University in February 2022. She is currently working with the GTU Masters’ joint program at CNU. Her research is mainly in the areas of North Korean English education and corpus linguistics. If you have any questions related to her research, please send her an email at 188884@jnu.ac.kr.