Alternatives to Public Schooling

Compiled by David Shaffer.

When we think of primary and secondary education in Korea, we think of the national public school system and the national curriculum that it is required to follow. But as any teacher knows, one size does not fit all in education. Accordingly, the government has made it possible for students to follow alternative pathways in pursuing their education. There are faith-related schools, prep schools heavily focused on university entrance, and schools for those who find it difficult to adjust to the typical public school system. These alternative types of schools and schooling are gaining in popularity, but so many of us still know so little about them. This article features the impressions of three English language teachers teaching at three different types of alternative schools in Korea. Here are their accounts.

Instilling Seeds of Hope

Jared Dela Paz came to Korea over a decade ago, and during his time here, he has been teaching English at Lincoln House Gwangju. Jared received his BS at Far Eastern University in the Philippines and his diploma in TESOL from Concordia University, Canada. He has been active in Korea TESOL in Gwangju, but a growing family and teaching duties are now taking up more of his time.

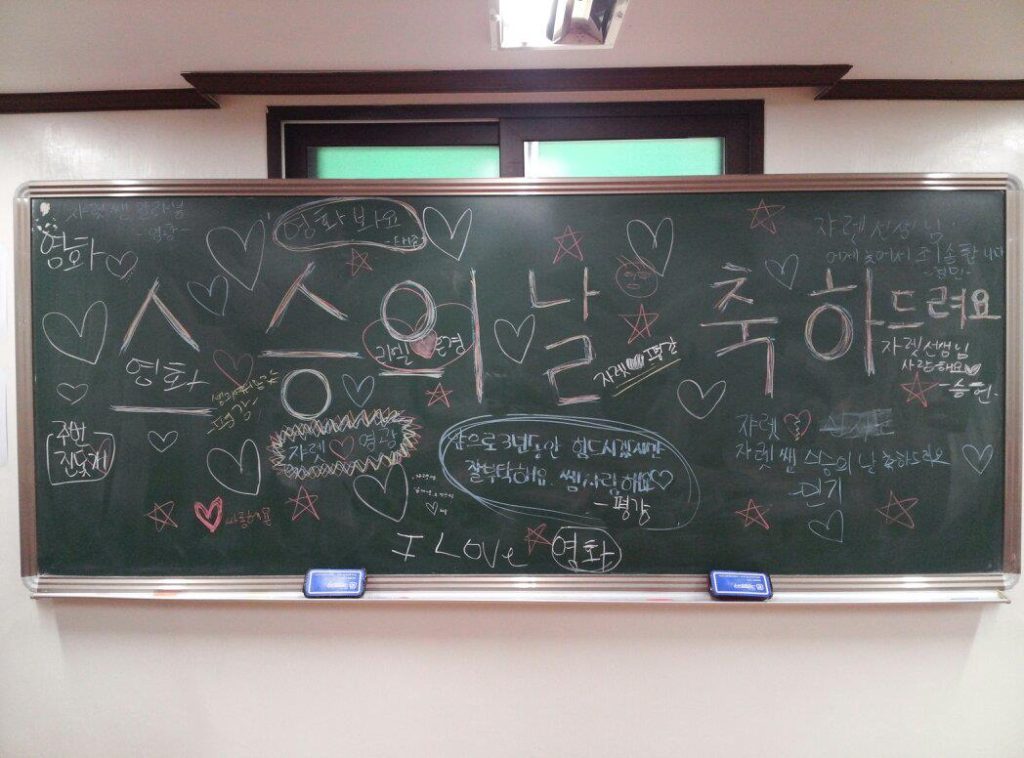

“Alternative education,” just by reading the first word, you already have that sense of what to expect. But if not, let me share with you my personal experience teaching the English language for eleven years at an alternative school. I came to South Korea in 2008 as a volunteer English conversation teacher at Lincoln House Gwangju, an alternative school. “Alternative school” (or daehan hakgyo, 대한 학교), leaves a bitter taste for many. They see “those” schools as a wasteland. A collection of hard-to-manage students, students with problems stacking up as high as the room ceiling, and students whose parents, teachers, and current school have already raised a white flag. Yes, to some extent, this description might be true. But this does not necessarily apply to all.

The current system of education in Korea is competitive. I believe that these students learn at varying levels. They do not need to be competitive to learn. They are freer and more unconventional. This is where alternative education steps-in. It provides students with a flexible curriculum where they can breathe and not feel suffocated by the pressure of getting a high score on a standardized test. Academics balanced with extra-curricular activities set out to reveal slumbering talents that the students might not even know they possess. Most of my students express themselves through art, digital media, music, and dance. Many students awaken a feeling of purpose and direction.

As educators in this field, our role is to guide these students to a path that they can grow and learn from, and become better members of society. These students’ English levels are sub-average. They could not afford to attend private hagwon or get tutors. They do not see that English is a necessary skill for their future. At this moment, my job changes from just being a teacher to being a mentor. I begin to tell them that “English” is like a key that opens many doors. When they hear this, they begin to get interested. By learning English, they can become more than what they are now. It is a language that builds bridges; connects people of all shapes, colors, and races; and a tool that can help them get into a good university and eventually a better future.

It is my job to instill seeds of hope in my students’ hearts and nurture those seeds, knowing that one day when everything is right, a tiny sprout will come out. Seeing the students gain hope is what keeps me in this profession. Because of this hope, they now have a purpose for studying and begin to dream. I dream that they will become global leaders of their generation. If I were to choose between a “regular” teaching job and a teaching job at an alternative school, I would most definitely choose the latter. It keeps me up at night, thinking of ways to get through to one student and plant that seed. In the future, my hope is that today’s “alternative” education will no longer be the alternative but become the mainstream in education.

Teaching at a Christian Alternative School

Ju Seong Lee is from Gwangju and received his BA in English education at Chosun University. He is a former volunteer and Korean teacher at the GIC during 2000–2003. In addition to Korea, he has taught in a variety of schools in a variety of multicultural contexts in the U.S., Hong Kong, New Zealand, Mongolia, and Thailand for more than 15 years. Dr. Lee received his PhD in curriculum and instruction at the University of Illinois in the U.S. He is currently an associate head and assistant professor in the Department of English Language Education at the Education University of Hong Kong. He is also a lifetime member of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of Korea TESOL. Here is his account of teaching at an alternative school in Korea.

I worked as an English teacher from 2010 to 2014 at a Christian alternative boarding school in Korea. Students and parents chose the school because it was established on a Bible-based philosophy. The school’s curriculum and instruction were flexible since they were not governed by the Korean national curriculum. The school curriculum consisted of core courses (e.g., Korean, mathematics, science, and English) and electives (e.g., arts and crafts, creative play, and cooking). At the time of my employment, more than 80 teachers worked at the school, including residential teachers (who lived on campus) and commuting instructors (who taught on a weekly basis). Since the school did not receive any financial support from the government, the tuition fee was higher than that of public secondary schools. So, the students were generally from higher socio-economic family backgrounds.

In the English department, there were seven Korean teachers and three native English-speaking teachers. Teachers usually worked from Monday through Friday, teaching 20 classes a week (45–50 minutes per session). The teachers were encouraged to promote student-centered autonomous learning inside and outside the classroom. But high school English teachers needed to adopt a teacher-oriented approach to prepare the students for the university entrance examinations, which was similar to what public school teachers did.

I would like to share four rewards of working in the Christian alternative school. First, since the school was free to choose its own curriculum, English teachers were able to integrate innovative and creative activities into teaching. This approach is different from a public school, where English teachers rely on the established national curriculum. Second, unlike a regular public school, most of the teachers in the alternative school were provided with an accommodation on the campus, furnished with basic furniture, home appliances, and an internet connection. A free, healthy meal was also provided every day, even during vacations. Third, since teachers and students were all Christians, they were free to worship and sing praises to God. Finally, since I was living on the campus, I spent a lot of time with students playing sports, eating together, and doing various activities. This helped me form a strong personal relationship with students.

There were some challenges as well. First, since it was a Christian boarding school, I had to play multiple roles, including English teacher, homeroom teacher, Bible reading facilitator, counselor, and administrator, which made my daily schedule hectic. Second, since the school did not use a textbook endorsed by the Ministry of Education, I had to prepare everything (e.g., teaching materials, quizzes, assessments, PowerPoint slides) by myself or in collaboration with colleagues. Third, since the school did not receive any financial support from the government, there was limited funding and financial support for teachers’ professional development.

For those who are interested in working in a Christian alternative school, it is wise to first visit the school, talk to some teachers and students, and get firsthand information about the school. After collecting accurate and comprehensive information about the school, you can make an informed career decision. Also, unlike at a public school, teachers may have limited opportunities for teacher professional development. So, I suggest you develop and engage in self-directed professional development through writing reflective journals, creating a teaching portfolio, conducting classroom observation, and conducting teaching evaluations from students.

A Perspective from Kwangju Foreign School

Derek Iwanuk is from Canada and has degrees in English Literature and communications (BA, Wilfrid Laurier University) and English (Honors BA, University of Massachusetts). He has been teaching for 11 years. Derek came to Korea in 2009 and has been in Gwangju the past three years teaching at the Kwangju Foreign School. His account of his teaching experiences there follows.

Over the last three years, I have been blessed to work at Kwangju Foreign School as the middle school English language arts and writing teacher. Previously, my area of concentration was ESL in one of the many after-school academies situated throughout Seoul. When I am asked about my experiences working at an international school versus an after-school academy, or hagwon, my first thought is how the instruction is delivered.

At an international school, the entire community and its subjects (with the exception of specialized language subjects such as Chinese or Spanish) are taught in English. Metaphorically, our students are exposed to English as a fish is to water. Students here learn in English, as opposed to learning English as an additional subject. In my experiences, this holistic approach to the language allows for a great acquisition of English over an extended period of time. Moreover, it prepares our students for the cultural challenges that they will face when they inevitably enroll at a post-secondary institution in an English-speaking country.

As a school, one of our primary goals is to prepare students emotionally, academically, and socially for life in a Western culture, and the acquisition of not only the technical aspects of English but the cultural aspects of the language as well is essential. Another one of our goals at Kwangju Foreign School is to promote and implement learning beyond the classroom. Before COVID-19, each division (high school, middle school, and elementary) was encouraged to organize at least one field trip a quarter to promote hands-on learning experiences. Our elementary division organized a field trip to a nearby salt farm and our middle school division organized an overnight trip to Seoul to experience the Korean Wartime Museum and the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). These activities allowed our students to experience hands-on learning as well as cultural and historical learning in an immersive and interactive environment.

Another advantage of working at an international school is that although we do follow Common Core standards and benchmarks, and administer standardized testing, we have the freedom to implement our content in a variety of ways. This is one of the major advantages of working at an international school, especially at Kwangju Foreign School, which emphasizes project-based learning: We have the freedom to use our creativity when developing unit and lesson plans. Moreover, this allows our teachers to infuse the use of technology into our lessons and challenges our students to solve real-world problems. For example, our social studies teacher created a project that challenges our students to create a subway line for Gwangju. The students must take into account a variety of issues that they could possibly encounter, such as city planning, economics, population density, and utilitarianism. Not only must they look at the logistics of the project, but they must explore the challenges that they could face with a large public project.

One of the challenges that I have faced at Kwangju Foreign School is bridging the culture gap between the Korean and the broader Eastern philosophy of education with those of the West. On a couple of occasions, we have received critical parental feedback regarding the lack of testing and traditional methods of Eastern pedagogy. In response, we opened the lines of communication with the parents and explained the value of our approach and how this approach is beneficial to their child’s academic and emotional growth. The value of this communication has been instrumental in developing trust between parents, students, and our faculty, and I believe that this building of trust has helped us foster the cooperative relationship within the members of our school community.

Another potential challenge is that, as teachers, the planning can be considerably more involved. We are expected to create and design curricula to implement and deliver to students. We use Common Core standards and benchmarks to guide our instruction; just coming to school, opening a textbook, reading out of it, and having students fill in workbook exercises is not possible here. While most teachers love this creative freedom, it is not for everyone. Moreover, school-sponsored teachers who work in any foreign school in Korea are required to have an E7 visa and the main requirement of that visa is a government-issued teaching license.

Teaching at a foreign school in Korea is much like teaching in a US public school, providing it follows a US curriculum. Like any school, it has strengths and weaknesses. The holistic, integrated approach coupled with a focus on experiential learning make it stand apart from other schools. From a teaching perspective, the freedom of how to teach can be a gift and a challenge. Overall, though, for learning English, a foreign school is a great choice.

In Conclusion

Every teacher knows that no two learners in a class, let alone in a school, are the same. They come into the class with different levels of proficiency in the class subject, be it English or anything else. They come with different learning style preferences and different sets of learning strategies. They come with different aptitudes, different attitudes, different levels of motivation, and different aspirations. They may even have differing physical, cognitive, and emotional development. How can cookie-cutter schools meet the educational needs of such a diverse array of students? The public school system does provide for vocational high schools, but their small numbers and curricula do not sufficiently meet the need. In the United States, for example, even small public high schools with fewer than 100 students in a graduating class may have five or more different educational tracks for students to select from. With forward thinking in educational policy, Jared’s wish could become a reality: that alternative schools are no longer the exception but are part of the conventional schooling system.

Photographs courtesy of Jared Dela Paz, Ju Seong Lee, and Derek Iwanuk.

The Author

David Shaffer is an educator with many years of experience in the field of English education in Korea. As vice-president of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, Dr. Shaffer invites you to participate in the chapter’s teacher development workshops (now online) and in KOTESOL activities in general. He is a past president of KOTESOL, and is currently the chairman of the board at the Gwangju International Center as well as editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.