Creating a Student-Centered Classroom

By Dr. David E. Shaffer.

When I began teaching English in Korea, standard practice was to introduce new words by writing them on the blackboard (yes, they were black), saying the new lexical item several times, then explaining its meaning and using it in a sentence. The teacher might follow up by asking a student or two to make their own sentence using the new lexical item before handing out a worksheet to everyone. The worksheet might include a matching exercise, where students were to match the words in one column with their definitions in the other. A second exercise might be to write each of the new words in a sentence. And with this exposure, the student was expected to “learn” the new word, which in most cases required memorization.

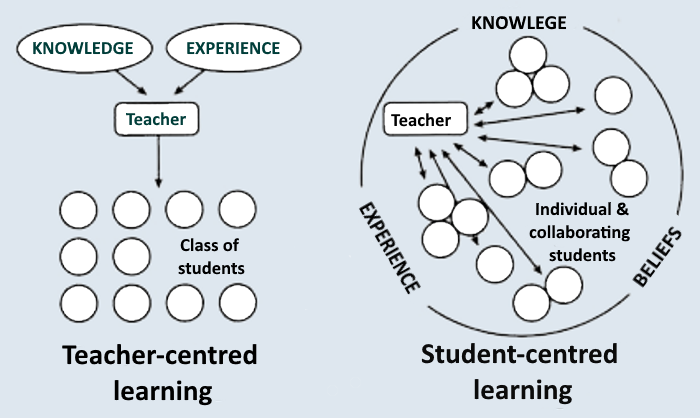

The banking model of education was trending. The term was coined by Paulo Freire (1970) as a metaphor of students as containers to be filled with knowledge by the teacher, that is, to receive, file, and store the deposits. The transfer of knowledge was thought of as being uni-directional, from the teacher to the student, much like an online bank transfer is now made. Freire was the first to criticize this traditional banking model, but in time, many would follow.

The banking model is a teacher-centered approach to learning. In this conventional approach, the teacher functions as the presenter of information to students, who are expected to passively receive it. It is still quite commonly found in Korea in many university lecture halls and in even more high school classrooms, whether it is an English classroom or that of another subject. The relative inefficiencies associated with teacher-centered learning have led to the development of student-centered learning, where the focus is on the student in the learning process rather than constantly on the teacher.

Let us look at both the teacher- and student-centered learning approaches and consider their advantages and drawbacks to show how focusing more on the student can make for a more enjoyable as well as effective learning environment.

The Teacher-Centered Approach

As teacher-centered learning has been the mainstay of classroom instruction for such a long period of time, it surely has some strong points. When instruction is centered on the teacher, the teacher assumes total control of the lesson and the students’ activities. That is, the class is orderly and the classroom is quiet. With the teacher taking direct responsibility for student learning, the class benefits from the focused approach to the lesson derived from the teacher’s carefully laid preparation and lesson plans. As the teacher has control of the class, they easily feel a sense of confidence in their teaching – self-assured that all students are provided with the same material and none are missing out. Also, student confusion is minimalized, as they always know that their attention is to be on the teacher.

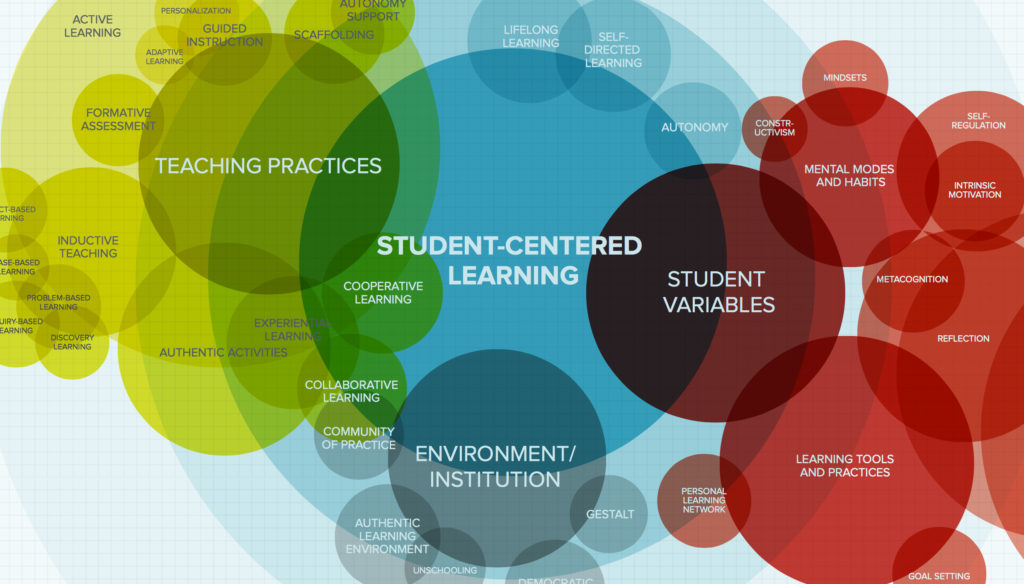

From the above, you may have deduced that with the teacher-centered approach, students work alone. Interaction with other students is discouraged (“Quiet, please!” “Do your own work!”). Since students participate individually, the burden is on the teacher to make the lesson highly interesting. If the teacher cannot hold the students’ interest, they will easily become bored, minds will wander, and learning will not take place. Collaborative activities such as pair work, group work, and project work are not part of the lesson, so students do not have the opportunity to share in discoveries, as is common in inquiry-based learning. Without collaborative activities, students have fewer opportunities to develop communication skills and critical-thinking skills, or for that matter, to develop the skill of collaboration, which is valuable in learning and essential in life.

The Student-Centered Approach

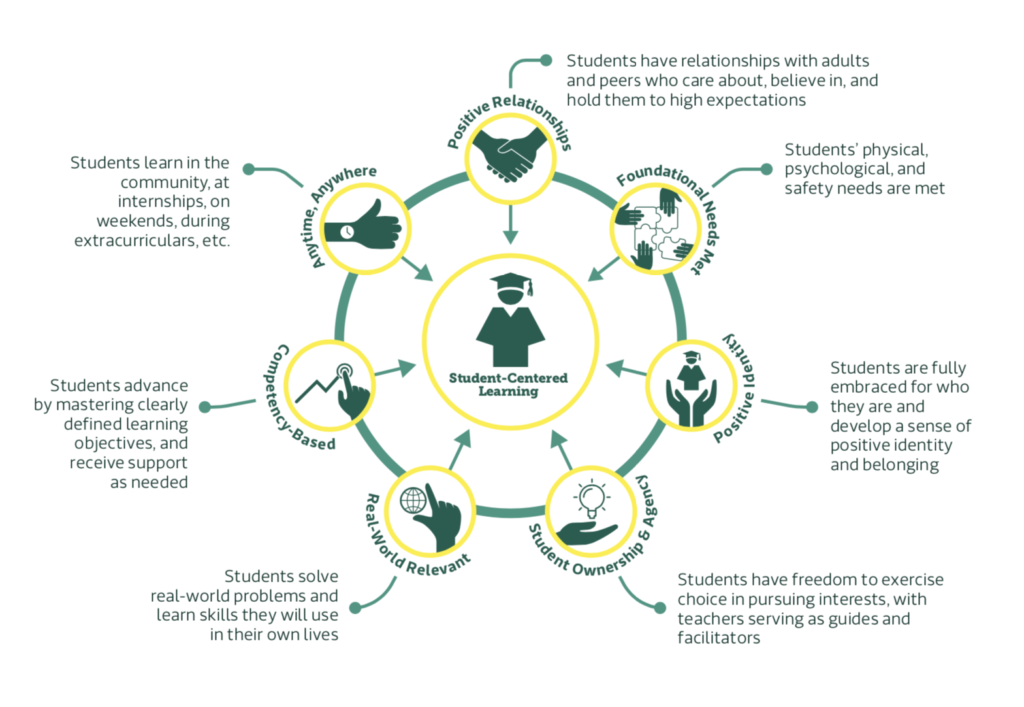

In student-centered learning, rather than the flow of information being one-directional, it becomes more of a sharing between the teacher and students, and also between students as they collaborate on tasks and projects. The life skills of collaboration and communication are fostered. While some activities are collaborative, students also learn how to work independently, which is also an essential life skill. The additional aspect of collaborative learning, in itself, adds student interest; they feel a sense of being in control of their learning process – they have agency. The focus of learning is on student inquiry and student discovery. And few will argue that knowledge gained through finding something out for yourself will not stick with you longer than if someone just tells it to you.

Student-centered learning does have its drawbacks also, but these are not serious if the teacher lets the students know what is expected of them. Because the student-centered approach releases students from strict teacher control, the classroom will become louder when students are working in groups. The teacher can keep the noise level under control with reminders to the students. I have always considered a certain level of noise in the classroom as a good thing, as it was an indication that students were interacting towards achieving their task goal. Classroom management can eat into class time, e.g., giving instructions, arranging groups, controlling overly noisy and overly active students, but once students become familiar with the routines, classroom management requires less time.

Implementation

If students are not familiar with the collaborative nature of student-centered learning, they may not feel comfortable and prefer to work alone; however, with time and increased exposure to collaborative work, they soon prefer it to individual work in class. With teacher-centered learning, the teacher feels more confident (though possibly falsely so) that each student is exposed to the same information (that which is delivered by the teacher), but with the discovery-based nature of student-centered learning, the teacher may be less confident that there are not any students who missed something. However, as every teacher knows, student uptake always varies from student to student in the same class regardless of the method of teaching.

All things considered, if implemented properly, considering the needs and preferences of the students in the class, student-centered learning is a more effective teaching approach than teacher-centered learning. It must be remembered that teacher-centered activities do have a place in student-centered learning – how much depends on the teacher’s and also the students’ degree of comfort with both student-centered and teacher-centered activities. Transitioning from a totally teacher-centered to a student-centered approach should be gradual, giving students time to adjust to the new, and most likely strange, classroom practices, thereby reducing the risk of resistance to the unfamiliar procedures.

Effective implementation of student-centered learning rests heavily on the teacher knowing their students – not just their names but their interests, learning styles, and preferences in skills they wish to focus on. Gathering this information on each student could take a considerable amount of time. However, Nunan (2015) has devised a student learning preference survey (next page) that makes the task easy for both the teacher and the student. Responses are on a 1 to 5 Likert-type scale to survey items of five types: topics, methods, language areas, out of class, and assessment. The teacher may add, subtract, and adjust items to make the survey more relevant to the group being surveyed. When teaching a new group of students, giving this survey on the first day of class could speed up the process of getting to know your students and their learning preferences. Whether your classes are predominantly teacher-centered or student-centered, you may wish to give this survey to your students just to see how closely your teaching dovetails with what the students consider their needs and preferences to be.

Learning Preference Survey

Complete the survey by circling the number that best corresponds to your own beliefs about how you like to learn.

Key: 1 = Not like at all, 2 = Not like much, 3 = Just so-so, 4 = Like, 5 = Like a lot

Topics

In my English class, I would like to study topics . . .

- about me: my feelings, attitudes, beliefs, etc.

( 1 2 3 4 5 ) - from my academic subjects: psychology, history, etc.

- from popular culture: music, films, etc.

- about current affairs and issues

- that are controversial: underage drinking, etc.

Methods

In my English class, I would like to learn by . . .

- small group discussions and problem-solving

- formal language study, e.g., studying from a textbook

- listening to the teacher

- watching videos

- doing individual work

Language Areas

This semester, I most want to improve my . . .

- listening 12. speaking

- reading 14. writing

- grammar 16. pronunciation

Out of Class

Out of class, I like to . . .

- practice in the independent learning center

- have conversations with native speakers of English

- practice English online through social media

- collect examples of interesting/puzzling English

- watch TV / read newspapers in English

Assessment

I like to find out how my English is improving by . . .

- having the teacher assess my written work

- having the teacher correct my mistakes in class

- checking my own progress / correcting my own mistakes

- being corrected by my fellow students

- seeing if I can use the language in real-life situations

(Adapted from Nunan, 2015, pp. 20–22.)

References

Freire, Paulo. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed (M. B. Ramos, Trans.; 2nd. ed.). Continuum/Seabury Press. (Original work published 1968)

Nunan, David. (2015). Teaching English to speakers of other languages:

An introduction. Routledge

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL UPCOMING EVENTS

Check the Chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and online activities.

For full event details:

Website: http://koreatesol.org/gwangju

Facebook: Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL

The Author

David Shaffer is an educator who has many years of experience in the field of English education in Korea. Over the decades, his teaching approach has evolved from heavily teacher-centered to heavily student-centered, and he is most gratified with the results. As vice-president of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, Dr. Shaffer invites you to participate in the teacher development workshops and their regular meetings. He is a past president of KOTESOL, and is currently the chairman of the board at the Gwangju International Center as well as editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.