Emergency Remote Teaching

A Whole New Ballgame

Compiled by Dr. David E. Shaffer.

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, public schools and universities throughout Korea have been forced to move their classes from their traditional face-to-face classroom environment to an online platform. The quickness with which this changeover took place left precious little time for English teachers to prepare – to redesign lesson plans, to get acquainted with an unfamiliar learning management system and new apps. Was teacher–student interaction feasible? Was student–student interaction possible? How could student assessment be conducted? These and many other questions, adjustments, and uncertainties seemed to present themselves all at once and needed to be promptly resolved. The present situation is so radically different from regular online teaching that it has been christened “emergency remote teaching.” It is a whole new ballgame! Presented below are the experiences of four area English teachers – teachers at the primary, secondary, and university levels who are members of KOTESOL’s Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter – and their accounts of how they have dealt with emergency remote teaching.

Everything Takes Longer

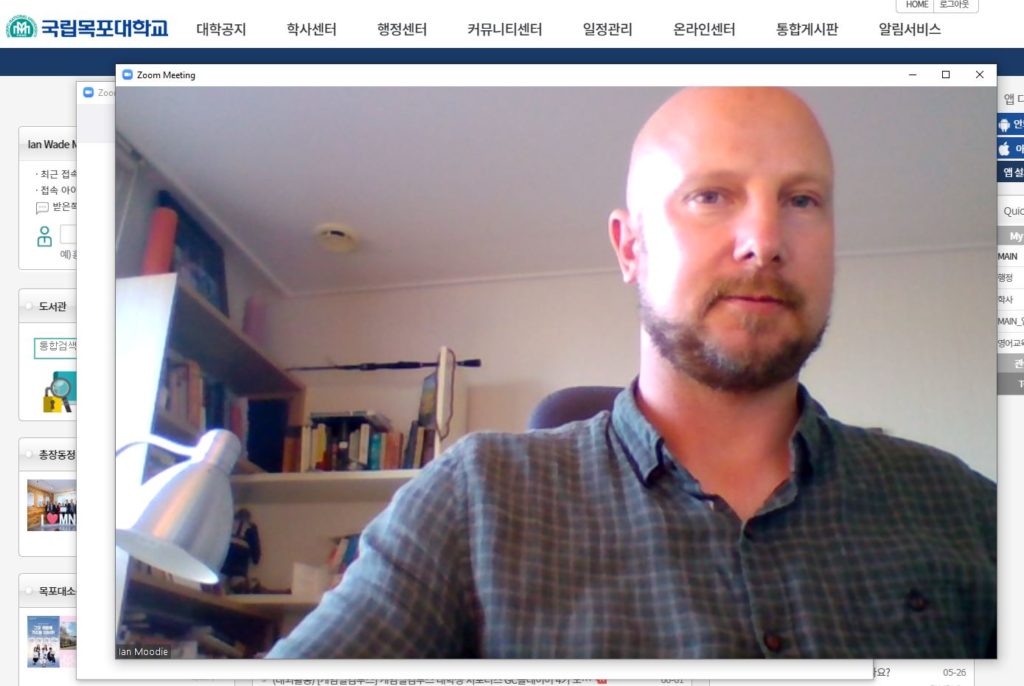

Dr. Ian Moodie is an associate professor in the Department of English Education at Mokpo National University in Muan, just north of Mokpo. He has been teaching in Korea for 15 years and for the past three years has been teaching English education majors at MNU. Here is his account.

When I first heard that we were going to teach online, I was relieved and not surprised. At that time, COVID-19 had already been deemed a global pandemic, many major universities had already switched to distance learning, and the major sports leagues of the world had suddenly shut down for the season, which made it clear to me that this virus was the real deal. However, that relief soon turned to uncertainty – and then to a mild frustration in realizing that everything I wanted to do was going to take a lot longer than I thought it would. Have you heard of Hofstadter’s Law? It goes something like this: Tasks always take 20 percent longer than you expect – even if you account for Hofstadter’s Law. I experience this everyday with online teaching.

At first, I tried to match my online coursework and activities as closely as I could to my previous lectures. However, I soon felt that this was not the best approach and have since modified the materials to better suit the medium. My courses (whether they be in pedagogy, English language, or linguistics) tend to involve a great deal of collaborative activities, but this has been harder to pull off online – harder for me to plan and harder for the students to complete. My students expressed a preference to be able to do the coursework at a time of their choosing and to not have to login at specific times for lectures or to do activities. Thus, my classes now involve mostly asynchronous learning, and I have had to accept that while this is not an ideal approach for efficacious language teaching and teacher training, it is a pragmatic approach to get through the semester.

There are some positive things arising from this experience, too. For one, being forced to cede to online instruction, I now have a deeper understanding of how to make use of blended learning in the future. I also feel that this experience will give stakeholders a renewed appreciation for the role that schools, universities, and learning institutes provide to our communities. Moreover, this experience has been a good reminder of the need to accept things how they are as opposed to how we wish them to be.

The Missing Feedback Loop

Brennand Kennedy teaches undergraduates at Dongshin University in Naju, just south of Gwangju. He has been teaching in Korea for six years and for two years at Dongshin. Here is his account.

When our university made the decision to transition to online courses this spring, I had very mixed feelings. In addition to keeping my job while not risking the further spread of the virus, it also allowed me to be much more involved in my daughter’s birth and her first weeks of life. However, with no experience teaching online and a brand-new career preparation course to teach, I knew that I was in for a rough semester.

One major challenge has been student engagement (or lack thereof). Although I considered conducting live lectures through video conferencing software, most teachers in my department have had to settle for uploading pre-recorded lectures along with the university-mandated 35 minutes of coursework per lesson. Initially, in hopes of retaining some semblance of real-time student interaction in what are supposed to be conversation courses, I naively asked students to adhere to the originally scheduled lecture times when participating in the video lectures. However, after two weeks of trying to enforce this rule, it occurred to me that some of my students might be lacking easy access to computers and/or the Internet, and may even be venturing out to Internet cafes just to participate in my lectures, thus defeating the purpose of the online courses. Although we live in what is often called the most connected country in the world, my hopes for some type of normalcy during such an unprecedented crisis turned out to be unreasonable, and I have since been giving students the entire week to (virtually) attend my lectures.

This initial oversight points to the more general challenge of interacting with students in an online setting. A large portion of what teachers do in the classroom occurs based on the real-time feedback we get from our students, whether it is the pace of instruction, the activities used, or the way we explain new language items. For me, online teaching has completely removed that feedback loop and the already hard work of understanding each student’s unique obstacles to language learning has become effectively impossible as few students are willing to communicate with me through any of the many available means. Sadly, after eight weeks there are only a handful of students whose names I have come to recognize. Where I used to be a coach for my students, online teaching has made me into a police officer, constantly monitoring to ensure that students are watching every video and completing every survey, quiz, and forum that I poured so many hours of work into creating. While I appreciate all new experiences, my students and I are hoping this experience will soon meet its permanent end.

Focusing on What I Can Do

Lisa Casaus teaches fifth- and sixth-grade students at Unli Elementary School in Gwangju. She has been teaching in Korea for four years and has spent most of that time at her present school. Here is her account.

The more limitations and obstacles humans face, the more we are forced to think creatively and innovate. Or so I remind myself.

The nature of my job, as a public elementary school guest teacher, is full of limitations. Officially, I am an assistant to a Korean English teacher. This means that the definition of my role can vary greatly based on my partnering teachers: their needs, wants, and teaching style. Other limits include the barriers of language, age, and culture, not to mention concerns about safety, that are present when teaching young learners.

EFL (English as a foreign language) teachers have developed ways to work with or around language and culture, but now, as we face the added limitation of a two-dimensional teaching space, our old solutions may no longer work. Our old activities may not be appropriate. It is time to create and innovate.

As an artist as well as an EFL teacher, creation and innovation are my favorite aspects of this job. But I often suffer from “idea-overwhelm.” Too much possibility can sometimes be worse than not enough. So, when applications like Powtoon, Mentimeter, Kahoot, and Flipgrid kindle my inner illustrator’s heart, I dream of interactive presentations, animated web-comics, and class blogs where elementary students engage each other in English! Possible? Probable? Probably not. I have to remember that reality and aspirations do not always match. What is realistic in this environment? What is realistic for myself and my students? Instead of focusing on what I cannot do, I need to focus on what I can do.

What I can do is search for and organize videos, worksheets, and online games that are relevant to the lesson being taught. I can modify and repurpose, or if need be, create from scratch. This is similar to what I have been doing before, only now I am not thinking about how to develop collaborative, tactile, and kinesthetic activities. Instead, my focus is on the audio-visual realm: thinking of ways to explain how to do an activity without the immediate benefit of body language, eliciting techniques, or comprehension checking.

I can learn how to make interactive worksheets and explainer videos. I can focus on what I am good at by illustrating Baby Onion video-stories. Baby Onion, my personal mascot, is a character who features in many of my lessons. Half of my students are already familiar with the character and his friends. I can create Baby Onion material – for hours and hours and hours.

And, I can remind myself that even though I love to create these materials, I also have to take into account time, energy, and utility. Re-clarify. Re-focus. Creativity within limits. I can remind myself that I must walk before I can fly.

Luckily, I Heard About BAND

Bryan Hale is a teacher at Yeongam High School in Yeongam, south of Gwangju, and the first vice-president of KOTESOL. He has been teaching in Korea for eight years, two years at his present school. Here is his account.

When talk first went around about the Korean school year beginning online, I worried that English conversation classes might be cancelled altogether or that authentic communication could be impossible anyway. This fear seemed justified when I started hearing about the learning management systems being considered and how focused they were on one-way delivery of content like video lectures.

Even the more interactive possibilities seemed to have big drawbacks. I teach at a rural high school, and I worried that something like Zoom might not be accessible to students with less technology. And I knew that many more students would feel uncomfortable videoconferencing with family members around.

Luckily, I heard about Naver’s BAND. Previously, I had thought this was only a phone messaging app, but I was happy to discover that it offers many of the communication features of social networking services in a private space with good accessibility for both phones and desktops. I campaigned to use BAND for my English conversation lessons, and fortunately, my school agreed.

Teaching live, synchronous lessons in a text-based chatroom has involved some challenges! It is tricky not being able to gauge students’ facial expressions and body language, but we have been using a lot of emoji and reactions, and I think we have established some new communication norms.

One of the benefits of text-based chat interaction is that it gives students more opportunity to focus on language, since the language they “listen” to does not disappear into the air, and they can be more thoughtful and deliberate about their output. At the 2018 KOTESOL International Conference, I saw a fantastic session by Jill Hadfield in which she spoke about creating online language activities similar to the kinds of interactions people naturally engage with on the Internet, and that really guided my planning about how to teach using BAND. Jill Hadfield and Lindsay Clandfield have a book called Online Interaction, and you can find some great videos of them explaining their ideas on YouTube.

As we move back to classroom teaching, I would like to establish blended learning by maintaining some of these beneficial aspects of online interaction using BAND.

Takeaways

Though teaching online may first give the impression that the instructor would have more free time, Ian conveys how online class preparation takes longer than expected – even longer than expected with extra time already factored in! He also points out the futility in trying to construct online learning to mirror in-person classes. Brennand highlights the challenge that fostering student engagement presents in an online environment and the lack of interaction, which leads to the absence of feedback on and from students.

Lisa stresses the need to create and innovate for online instruction, that is, the need to not focus on what cannot be done with online instruction but on what new possibilities the new medium presents. Bryan is thrilled to have found BAND, the text-based chatroom that is the closest thing yet to simulating face-to-face discussion, and the use of emoji to convey body language.

Being parachuted into unknown territory can be distressful, but after landing and surveying the new terrain, one can identify the direction in which to proceed to best accomplish their mission – in this case, emergency remote teaching.

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL – UPCOMING EVENTS

Check the chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and online activities.

For full event details:

Website: http://koreatesol.org/gwangju

Facebook: Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL

Photos courtesy of Ian Moodie, Brennand Kennedy, Lisa Casaus, and Bryan Hale.

THE EDITOR

David Shaffer has been a resident of Gwangju and professor at Chosun University for many years. He has been with KOTESOL since its early days and is a past president of the organization. At present, as vice-president of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, he invites you to participate in the teacher development workshops at their regular meetings (presently online). Dr. Shaffer is currently the chairman of the board at the Gwangju International Center as well as editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.