Environmental Awareness Through English Teaching: An Interview with Julian Warmington

If you have been around Gwangju for a while, you have likely heard of Julian Warmington – that pack of energy from New Zealand. Julian taught for years at Chosun University. During that same time, he also spent years contributing to a fledgling Gwangju News, where he wrote articles, served as co-editor, and later served as editor-in-chief. Julian was also considerably involved in Korea TESOL, serving for several years as editor-in-chief of The English Connection, KOTESOL’s quarterly magazine, as well as founding and being a driving force in KOTESOL’s Environmental Justice Special Interest Group. In this interview, we touch on all of the above but focus on how EFL instructors can instill in their students a strong sense of environmental awareness. — Ed.

KOTESOL: Kia ora, Julian. And thank you for making time for this interview; it is much appreciated. I like to start off interviews like this one by asking the interviewee what they did before coming to Korea and what it was that drew them to Korea. Will you begin with that?

Julian: I gained a BA in political science and English literature, then a post-graduate diploma in teaching, specializing in teaching in a second language. I worked as a primary and intermediate school teacher for three years and then wanted to travel overseas, like many younger Kiwis do, in what we call an “OE,” or overseas experience. Many New Zealanders travel to Australia or the UK, but I wanted to go somewhere with a very different culture for a more challenging and interesting experience. I had practiced taekwondo since secondary school, and so I knew a little about Korea, but it still seemed mysterious, and the more I read about work and life in South Korea, the more intriguing it seemed.

KOTESOL: I remember that you spent quite a few years teaching at Chosun University – I remember because I was also working there. Two things that stand out in my memories of those times are that you were much involved with a fledgling Gwangju News and later left Chosun for a couple of years. Could you tell us how you got interested in Gwangju News production and then why you took a hiatus from English teaching?

Julian: In my first year working at Chosun University, I wanted to take Korean language lessons. I heard about cheap, good-quality lessons at the GIC, the Gwangju International Center. During one of the first few lessons someone asked us students whether anyone would like to write articles about life as a foreigner in Gwangju. I agreed and was just starting to get to know the other foreigners involved when soon thereafter they all disappeared. They had had a disagreement internal to their group, and they all simply left: They basically ghosted the first, and at that time only, GIC coordinator, leaving her all alone holding the baby that was the newborn Gwangju News.

At that stage, they had developed it from a single leaf of black and white double-folded A3 paper with no editing, no spell checking, or photos, to a two-leaf folded newsletter with badly taken and very early digital photographs or obviously “borrowed” images downloaded from the internet. Let us just say I saw room for growth. I really enjoyed the process of suggesting and then helping implement improvements, seeing immediate results, and then looking for more ways to continually improve.

That was in 2001. By the middle of 2003, I had been working on it as an unpaid hobby and a busy part-time job for about two years, and as much as I loved both my teaching and working with the Gwangju News, my parents were unwell back in NZ, I had had a minor motorbike accident, and then my motorbike got stolen. I took the combination of all these things as a sign that it was a good time to return home and start some postgrad study, and so I did, starting on my master’s degree in English literature.

KOTESOL: As members of KOTESOL, we also had the opportunity to work together for a number of years. I am referring to work on TEC – The English Connection – KOTESOL’s quarterly magazine. Could you describe that experience as TEC’s editor-in-chief?

Julian: The best art is created within a set of restrictions, for example, only using one type of brush stroke, or a certain set of colors. Within the realm of business management, institutional knowledge is of crucial importance in order to avoid the mistakes and survive through the trials of a hard-won history. I had heard somewhere through the grapevine that a previous editor-in-chief had departed in frustration at not being able to find ways around those restrictions. Well, I knew almost nothing about art history, nor business management, but I did know those two lessons I had learned, and so consciously chose to see the suggested restrictions as dangerous mistakes to avoid as being fun challenges to creatively work around.

My favorite example is that of changing the cover images. Many people I had chatted with about TEC had voiced something like boredom with the endless images of panoramic vistas of flowers and trees. The obvious solution for a magazine about people working within a people-oriented business is to put a photo of a person on the cover, but for reasons proven by repeated and previous history, that option was precluded, so I took the challenge of getting a good high-powered digital camera with a big zoom lens and finding images of something related to education in Korea that interested me enough to take the best photos I could. That happened to be schools of any sort with solar panels on the rooftops. So, yeah, it has little to do directly with EFL in South Korea, but on the other hand, it is a lot closer to that topic than a close up of a spring blossom, or another panoramic vista of a hillside of trees with a temple in the middle!

KOTESOL: Yes, I remember that when you were called back to the role of TEC editor-in-chief for an additional year, the TEC covers and some of the TEC articles took on an environmental protection slant. By this time, you were quite involved with KOTESOL’s Social Justice SIG (special interest group) and later became one of the founders of the Environmental Justice SIG. What caused your interest in these areas to become so deep, and what work within KOTESOL did you do in these areas, in addition to the above?

Julian: In the years 2011 and 2012, I was working at the Gwangju Institute of Science and Technology. I met many postgraduate students who were researching cutting-edge technology on things like solar panels and battery components, and part of my job was to edit their theses and articles prior to sending them for publication in top international journals like Science and Nature. I became increasingly interested in the science of both the problem and potential tech responses. Then in 2014, two things happened: I moved to Busan to live with my girlfriend, and I watched a then-newly-released documentary film that changed my life.

In Busan, I traveled across the city by subway every day and so started listening to a lot of podcasts about these same things. I became somewhat depressed: Traveling by crowded subway on the 40-minute journey each way every day was enough to induce claustrophobia. But even more than that, I had realized just how bad the situation had become and how the governments of our “Five Eyes” countries had not only not been doing anything positive, but had actually been actively working to delay and derail all progress both at annual international climate summit meetings, and of course, within our own countries.

Perversely, by far the majority of English teachers in South Korea come from those five countries: the UK, the USA, Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand. So those of us lucky enough to have benefited from work in South Korea have also benefited from our earlier lives in some of the most highly industrialized economies in the world that have created the most pollution of all sorts.

For example, one of the worst sources of atmospheric pollution is from airplane exhaust fumes, as the large amounts of jet fuel exhaust is emitted much closer to the upper atmosphere where it does a lot of damage, by trapping heat much more quickly than the same amount of exhaust put out at ground level. Many of us living and working in South Korea fly home to our “Western” countries regularly – perhaps not as often as some business reps fly, but still – our lifestyle and older relationships are dependent upon this highly polluting and intensely indulgent aspect of our industrial economy lifestyle that we entirely take for granted. If everyone in the world could afford to fly as often as we do, the climate crisis would be much, much worse.

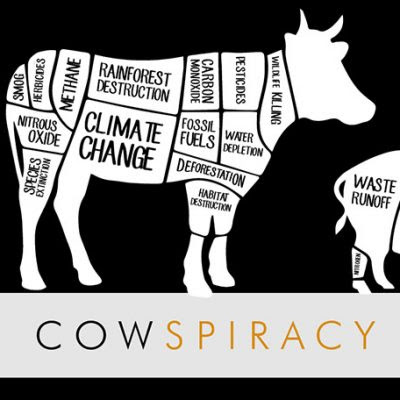

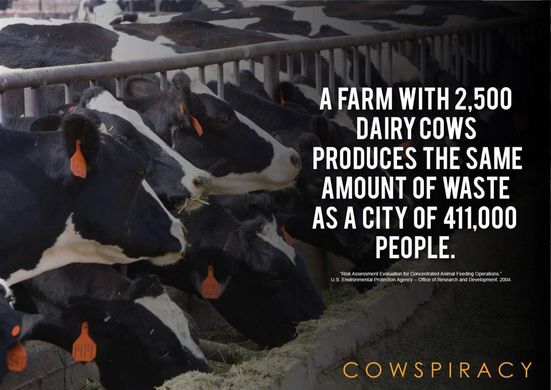

But the second thing that happened in 2014 was the release of the film Cowspiracy: The Sustainability Secret, which is now on Netflix. It was filmed in California and is about the devastating effect of the animal agriculture industry on the wider environment. I looked at it and just saw exactly the same set of issues occurring in my homeland of Aotearoa NZ. As an undergraduate at university, I had done a lot of white water kayaking on some of the most beautiful and naturally pristine rivers around the country, and at that time, in the late 1980s – early 1990s, we could stop in the middle of a river when thirsty and simply drink handfuls of water.

But in 1996, a new bill was passed into law that deregulated the dairy industry, and that allowed dairy farmers to force-breed more cows per year and removed limits on how many cows could be grazed within a one-hectare block of farmland. As a result, well over half the rivers and lakes around the country are not only too badly polluted to drink from, but you cannot even swim in most of them, nor at half the beaches around the country in summer after a rainfall. Dogs have died from drinking from polluted lake water. Most of the native fish species are threatened with extinction. Having seen for myself and even played within the natural beauty of those rivers and then learning the reason for their virtual destruction, I felt not only more depressed but also hopeful that this film could help inspire more people to understand the issues and start making the widespread cultural changes so desperately needed, and so dangerously avoided by our governments.

I learned from somewhere the maxim: “The antidote to despair is action,” and so, my girlfriend and I hosted the Busan Climate Change Film Festival. It was a positive thing, but it was not enough. I realized the very act of promoting the event through media publicity was likely as effective as the screenings to the few folks who actually came along. But then again, there is that other saying – Quality, not quantity! – by which I mean that one of the few people who did attend a screening of Cowspiracy was one Rhea Metituk, then a Busan-based professor with whom I went on to collaborate in forming the KOTESOL Environmental Justice SIG.

Anyway, for all these reasons, I felt more motivated to look for other ways to communicate what I had been learning and felt responsible to try to share what I had been learning with other English teachers in particular.

KOTESOL: Now for the main question that I have been leading up to: Considering the importance of protecting our environment and the seriousness of climate change, what can the average EFL teacher in Korea do to incorporate an awareness of environmental protection into their lessons and indeed into their curriculum?

Julian: Hmm. This is the big question, and so to keep it simple, I am going to offer you only three different answers. Let us start with the late great Doug Baumwoll’s [former writer for the Gwangju News] approach. Doug advocated simply incorporating examples relevant to your preferred topic into your regular examples that you would give to help illustrate any lesson objective. For example, if you were teaching a class about comparatives, you could compare candies and discuss which is sweeter, or chewier, or more expensive. Doug would perhaps say to do that, and then follow it up with another example, perhaps comparing the Kia Niro with the Hyundai Kona, or the Ioniq 5 with the EV6: Which has the longer range? Which has faster acceleration? Which has a more attractive chassis design? Which is more affordable?

A second answer is to know both the needs of your students and your own strengths and interests, and then focus on them. This may sound too obvious and redundant a statement, but we need to take what appears at first glance to be simple and obvious and apply it to this new context. If you are good at art, use that strength to inspire and motivate students to express what they learn creatively through art of some sort, following your models on a subject you are genuinely interested in and can become enthusiastic about. You do not need to focus on the depressing aspects of the climate crisis. That is why talking about electric vehicles appeals to me: It is a positive response to the polluting, old gas car problem. South Korea is now producing some of the best pure-electric cars available anywhere. Korean students can feel proud about them and the batteries LG Chem and others are producing. Electric vehicles alone will not “save us” from the impending and rapidly worsening storms, droughts, floods, and food price rises, but they are definitely an important part of finally limiting the power of the corrupt, old fossil-fuel industries and old car companies.

Thirdly, let us discuss for a minute what not to do. It is really very important to avoid the trap of asking students to debate whether our industrial climate crisis even exists in the first place. It appears to be common practice at least for some international schools in South Korea to take this shockingly misguided, lazy, and inappropriate approach. It is misguided because it is to give over to the fallacies of false balance and false equivalence. Some media companies take this approach and might, for example, have a company representative appear in a panel discussion alongside a scientist. The company rep might be a better public speaker than the scientist, but there is a vast difference between being an effective communicator on the one hand and having a valid and important message on the other. Students need to be able to see this difference and identify it for themselves.

To teach this subject in that way is worse than a cop out. It is a chronic failure of professional responsibility. If an English teacher in South Korea does not “believe” in our industrial climate crisis, or more accurately, if they do not understand the science yet, then it would be much more useful to avoid the topic altogether and instead focus on teaching media analysis skills, or critical-thinking skills, or team-building and cooperation skills within another context altogether.

KOTESOL: Could you give some specific examples for primary-, secondary-, and tertiary-level learners?

Julian: “Carol” is a teacher of new entrant students in Busan. She took her very young students on a field trip to the local garbage dump and to recycling centers to learn about what actually happens to waste in that city. Students expanded their vocabulary through the nouns to do with various types of garbage and also the verbs for what to do and not to do with each type of trash: Recycle this by dropping it off here, for one example. Hopefully, if taught well, it also shares the value of and provides practice at thinking globally while acting locally.

Also, I have a Kiwi friend in Tokyo, Japan. “Jon” is a journalist who taught himself to grow his own vegetables inside and in small parcels of land within the neighborhood. For the last few years, he has been teaching students at about six different schools how to grow their own organic vegetables. Jon sees extra value in teaching students the value of working towards being independent and self-sufficient in producing their own food. I also see it as being a great way for students to be proactive in a positive response to the frightening face of the crisis, and to realize the taste of freshly picked vegetables, and just how delicious and nutritious they can be. And again, if teaching comparatives and/or superlatives, this would be another great context for primary school students.

By secondary school age, students understand more of the STEM subjects and also the reality of the dire nature of our situation. Comparing and contrasting more details to do with pure electric cars is great for a positive theme for this age set, but also studying the increasing frequency and severity of storms, droughts, floods, or heatwaves; or learning vocabulary like wet-bulb temperature; or how to cook a vegan burger patty out of brown rice, beans, and chickpeas, and make a video report on it; or a shared report in response to viewing the film Cowspiracy or the more recent Milked (NZ, 2021) are all excellent and age-appropriate, language-rich learning activities.

At the university level, we could take any of those secondary school activities and include a more meta-thinking approach, for example, have students survey other students in class as to their response to viewing a film like Cowspiracy, or even just a portion of the film that you watch together in class and then discuss afterwards. Create a set of questions in response together, but preferably have your own set ready to offer if they do not come up with any themselves. Then share those questions in groups of students for them to ask and answer each other. Remember to first brainstorm and share sentence beginnings to support lower-proficiency students, clearly including whatever other language objectives you want to highlight. For example, if you are teaching plurals and/or the possessive “s” ending, highlight the difference between “one student’s response to a survey being that he would never eat meat again,” “two students’ replies included the information that they could never give up meat but that they are prepared to try a vegan burger at Burger King,” and “three students decided to replace cow’s milk ice cream with that new brand of soy milk-based ice cream you can get from Coupang now.”

KOTESOL: You are back in New Zealand at present. Could you tell us what you are doing there, what projects are you working on – TESOL-related or otherwise?

Julian: I have returned to be with my family as my mother was diagnosed with a mixture of Alzheimer’s and vascular dementia at the start of last year, just after she started asking me to come home frequently on Skype and Zoom calls. I am doing two things for the TESOL scene in South Korea these days: Firstly, I am working with other teachers there on a website of environmental lessons for South Korean EFL students and their teachers based on a regular 14-week curriculum of language objectives. This is to create a kind of easy-access, ready-to-go resource of ideas and content to either teach wholesale within a dedicated course, or for teachers to simply pick and choose topics to include in class when they are comfortable, much as Doug Baumwoll suggested doing. Secondly, I am offering a new presentation to local KOTESOL chapters. It is entitled “Tipping Points, Hope, and A-ha: How Your Students and K-pop Can Help Save the World from More Seoul-Type Flooding.” I am also available for Zoom presentations to local chapters on a topic of their own choosing, within the context of environmentally themed TESOL education in South Korea.

KOTESOL: You are keeping busy! May I ask what you like to do in your spare time – if spare time is something that you have the luxury of?

Julian: When I came back to Aotearoa, I not only missed my girlfriend still just south of Seoul, but I came back to another very cold, wet, and windy winter. I did get more exercise but not enough for a full-length Ironman Triathlon, and especially not after celebrating being back by eating too many vegan pies and ice creams. Over the last month or two, I have eased up on all that and got back into swimming, cycling, and jogging. I am also enjoying house sitting and getting to know more locally based humans and their feline and doggie overlords.

KOTESOL: As a final question, where do you see yourself being and what do you see yourself doing in, say, five years from now?

Julian: In another five years, I hope our team will have published a textbook on environmentally themed TESOL lessons catering to the needs of teachers teaching South Korean students. I also hope to have published a vegan recipe book for children in Aotearoa NZ and to have successfully encouraged a journalist friend to publish a book on vegans in South Korea, including athletes, celebrities, and other high achievers. I also hope to have completed and survived my first full-length Ironman Triathlon and perhaps started ultra-long-distance marathons, meaning 50 kilometers or more.

KOTESOL: Well, Julian, I can see that you are not only committed to the teaching of EFL in Korea, but also to being healthy as a vegan, and even more importantly, to saving our abused planet. Thank you for the glimpse into your works and ways – both professional and personal.

Interviewed by David Shaffer.

Photographs not marked are courtesy of Julian Warmington.

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL Upcoming Events

Check the Chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and other online and in-person KOTESOL activities.

For full event details:

- Website: http://koreatesol.org/gwangju

- Facebook: Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL

The Interviewer

David Shaffer has been involved in TEFL and teacher training in Gwangju for many years. As vice-president of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, he invites you to participate in the chapter’s teacher development workshops and events (online and in person) and in KOTESOL activities in general. He is a past president of KOTESOL and is currently the editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.