The Joys of Teaching

Expat Educators Explain

Compiled by Dr. David E. Shaffer.

Many of the English teachers coming to Korea to teach do so with the intention of staying for a year, maybe two, and then moving on. But there are also a considerable number of expat teachers here for whom that one or two years has turned into one or two more, and even into one or two decades more. What is it about teaching in Korea that keeps teachers here for extended periods of time? Four educators in our area have been asked exactly what it is that they enjoy about being an expat teacher in Korea. The following are their accounts.

A GIFT I GET TO WITNESS

Maria Lisak has been teaching for nearly 24 years, and for much of that time, she has been teaching in Korea, including 15 years in Gwangju. She is presently teaching mainly content courses in the Department of Administrative Welfare at Chosun University, where she has worked since 2012. Maria holds a master’s degree in education and a second master’s in business administration. She is currently completing her doctorate of education and is a past president of Korea TESOL’s Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter. Here is Maria’s account of the joys she gets out of teaching in Korea.

I love teaching. It’s not the job I expected to have when I was young, but when I came to South Korea and started teaching, I felt more at home in my life and career than I ever had before. What always keeps me going through any hardship is seeing the lightbulb go off for a student. When they’re struggling to make themselves understood or to understand, and suddenly that light in their eyes just pops – this is a gift that I get to witness, and I’m so grateful.

Teaching motivated students is always the easiest kind of teaching. When students are motivated and invested in their own learning, as a teacher I get to be a true guide on the side instead of feeling like a dentist pulling teeth. I’m always very grateful for motivated students, as I get to learn a lot about them and their ways of seeing the world. So really, it’s my learning, not just theirs.

Another thing that makes me happy is when students show initiative. I don’t expect students to always follow along; I expect them to ask for what they need and want to learn. Showing that kind of guts is tough. I respect students who have the courage to speak up for themselves, especially within South Korean culture, where the teacher–student relationship is so hierarchical. Passive students are always harder to teach because it’s more about a teacher-centered classroom than a student-centered classroom.

While motivated and invested students, as well as those who take initiative, bring me a lot of enjoyment, still some of my best memories are the struggling students who don’t give up and continue to show up. I always await that light in their eyes that something had meaning for them. A pure moment of joy! It’s my hope that my university keeps renewing my contract so that I, too, can keep living my dream here in South Korea!

IMMERSION: THE COOLEST EXPERIENCE

Jonathan Moffett came to Korea in 2016. After teaching for two years at the elementary school level, he now teaches at three different middle schools in Gwangju. Jonathan has a master’s degree in education from the University of Missouri and is a member of Korea TESOL. Here is his account of the satisfaction he gets out of teaching in Korea.

Since my arrival in Korea four years ago, I’ve had innumerable positive and simply unforgettable experiences. For my present purpose, however, I’ll focus only on those related to teaching itself. For my first two years in Korea, I worked in various public elementary schools, four different ones to be exact. Without a doubt, the fondest memories I have of those times were the simple enthusiasm of the students, and the absolute pure and unbridled joy shown to me. I was especially happy when, during my weekly class, students would all rise from their seats and cheer as I entered the classroom. They really enjoyed learning with games, such as running dictation, a real staple for my classes when things around the world were more normal. Students really seemed to enjoy interacting with English, not just learning about it through textbooks. Seeing this evidenced through their eagerness for class each week was really satisfying.

I was also really pleased when students would ask me questions about America, and what life was like for me back at my home. They seemed genuinely interested. Talking about various cultural differences, such as Americans not usually sleeping on the floor, not using chopsticks, and not eating rice with every meal, always filled my students’ eyes with wonder. It made me feel not only important but privileged to be the one who got to show them about cultures outside of Korea. In this regard, they were really insatiable for their desire to know more. For higher grades, teaching English related to making purchases often came up, and for this I always had some American money in my wallet to let the students interact with – they really loved this, though sometimes certain students were reluctant to give up the coveted dollar bill they clutched so defiantly.

After about two years of teaching at elementary school, I was invited to teach at an English immersion camp for middle school students for a week with three other teachers. This program is no longer running, but I can say without a doubt that it was the coolest experience of my teaching life. The students who attended were all very good at English, and everyone stayed overnight at the camp for an entire week. The week was filled with various activities and games in which English usage was the central purpose; it wasn’t traditional teaching, but more immersion in the true sense of the word. By the end of the week, I’d gotten to know so many unforgettable students, and had a great time with many friendly teachers.

The feeling that remained after the immersion camp was that English wasn’t just about cultural education and fun, like I’d felt when teaching elementary school, but also about useful, important, and sincere communication. After this experience, I decided to transfer to teaching at the middle school level, where I strive every day to combine the lessons I’ve learned from both levels of teaching to provide the best and most beneficial experience possible for my students. It’s this continual pursuit of delivering the greatest lessons I can for my students that continues to keep me here in Korea for the foreseeable future.

SOUL-SATISFYING CONNECTIONS

Lindsay Herron came to Korea in 2005. After teaching at the high school level for three years, she moved to Gwangju National University of Education, where she teaches English and teaching methodology. Lindsay has master’s degrees in language education and cinema studies, and is completing her doctorate in education. She is the president of Korea TESOL and an officer of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter. Here is her account of the gratification she gets out of teaching in Korea.

There’s a lot I love about living and teaching in Korea enough to keep me here for more than fifteen years, certainly! Life here boasts many amenities that were lacking from my life in the United States, such as universal health care and easily accessible clinics, convenient and affordable transportation options, reasonably priced restaurants (serving amazing food!), a low crime rate, and a community-minded willingness to make small sacrifices for the greater good (e.g., by wearing masks not only now, during COVID-19, but more generally when one is ill). At the same time, I also appreciate being outside many Korean norms. I’m not subject to the same social pressure to get married, for example, and while the ajummas (middle-aged women) at my gym might comment curiously about the slippers I wear in the shower, my unusual behavior is usually tolerated, chalked up to cultural differences.

There are many perks more specific to teaching, as well. I love the widespread appreciation for education and the attendant general respect for educators. I adore my students’ vocal responses when they’re amazed or impressed; few things warm my inner-showman’s heart more than a collective “Whoa!” in response to a video clip or story. And I love that I can relate to my students as a person rather than just as a teacher. In contrast to my own youthful conviction that teachers probably didn’t exist outside the classroom walls, my students here are curious about my life, and we take great delight in introducing each other to new music, movies, TV shows, and trends. I love discovering my students’ passions and talents; I love attending their performances; I love being able to hang out with them and cultivate a more social relationship than I had with most of my own teachers.

I also love many aspects of being, in particular, a foreign teacher at my university. I love the housing provided for me in the university dormitory, a perk I believe is unique to the foreign instructors. After spending thousands of hours commuting to and from my old jobs in New York City via a sweltering, stifling, rather malodorous subway, being a mere six-minute walk from my classroom is breathtakingly refreshing – literally, as my path takes me through the lovely campus that serves as my front yard. I love not being required to attend (all-Korean) faculty meetings, but also cultivating new friendships with university staff who want to practice their English. Finally, I love playing a role that few others at my workplace can play, offering a perspective that’s both inside and outside Korea. This, in turn, can give students space to discuss concerns that might otherwise be frowned upon, challenge dominant discourses about foreigners, and provide students with a chance not only to use English in an authentic way, but also to encounter, explore, and value diverse ways of being in the world.

Ultimately, it’s the relationships I’ve formed – with my students, the staff at my workplaces, other educators, and people in the community – that are most gratifying for me; these soul-satisfying connections are one of the primary reasons I stay in Korea year after year!

A CLASSROOM CULTURE OF WARMTH AND PLAYFULNESS

Bryan Hale has been teaching English in Korea since 2012 and has experience in both academies and public schools. He is now in his third year of teaching at Yeongam High School. Bryan has been active in Korea TESOL for most of his time in Korea and is currently the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter’s president. His master’s degree in applied linguistics (TESOL) is from the University of New England (Australia). Here is Bryan’s account of what he enjoys about teaching English in Korea.

Korea can be a really vibrant and rewarding place to work as a foreign English teacher. I think we sometimes overlook exactly how central English is truly becoming here. During my time teaching in Korea, exports like pop culture, gaming, tourism, and international education have only gotten bigger and bigger, and English is vital to all of them. It’s exciting to connect classroom teaching to social changes going on around us, and foreign teachers are often well-placed to make the most of this.

This vitality extends to the English language teaching (ELT) profession and professional development. Korea’s interconnectedness, both internally and with other countries, and its position in the world really make it an ELT hotspot. Of course, as Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL chapter president, I’m going to plug KOTESOL opportunities – I really do think KOTESOL’s conferences are some of the most engaging and accessible in Asia. As well, I have had great experiences being able to connect with other teachers (both in Korea and in other parts of Asia) for support with study and to collaborate on all kinds of ELT-related projects. Although I undertook my master’s degree through an Australian university, I think I greatly benefitted from being in Korea while I did it.

The Korean education system, of course, has some problems, but I think there are positive aspects that we may neglect to appreciate. Although I do sometimes find the hierarchy of Korean schools stifling, I think there is a positive flipside. Compared to Western teaching contexts, here teachers and students are more distant hierarchically, but also kind of socially closer and more familiar. During experiences teaching in the West, I was disappointed to sense a gulf between teachers and students, and I really missed the sparkle of Korean classrooms. I think that here, when things are going well with a particular class, we’re developing our own discourse of playfulness, gentle teasing, affection, and community within the traditional institutional structures around us. Korean classrooms can nurture surprising, maybe paradoxical, authenticity. I think I have definitely become quite attached to these aspects of my work here!

Professional opportunities and connections, life in a vibrantly interconnected society, and a sometimes underappreciated classroom culture of warmth and playfulness have all kept me teaching English in Korea.

IN CONCLUSION

The accounts presented above are from four expat educators teaching in Korea for different lengths of time and in varying teaching situations. The enjoyments that they have recounted here are numerous and diverse, but there are several evident commonalities in their accounts. They all express a deep-seated love for teaching, and especially for teaching in the Korean context. They thrive on interaction with their colleagues and students. Though Korea is so different in many ways from the English-speaking countries from which these educators have come, from what I know about these individuals, I feel confident in saying that they also have an affinity for Korea, Korean society, and Korean culture.

On top of this, they are concerned about improving their own teaching skills and the teaching profession in general. This they need not attempt to do solely on their own, as professional development can be achieved through a local community of practice within which Korea TESOL plays a significant role.

The above accounts may give the impression that the individuals giving them are looking through rose-colored glasses. That however is not the case; in an upcoming issue, these same four teachers will have their glasses off in describing the challenges that expat English teachers face in their profession in Korea.

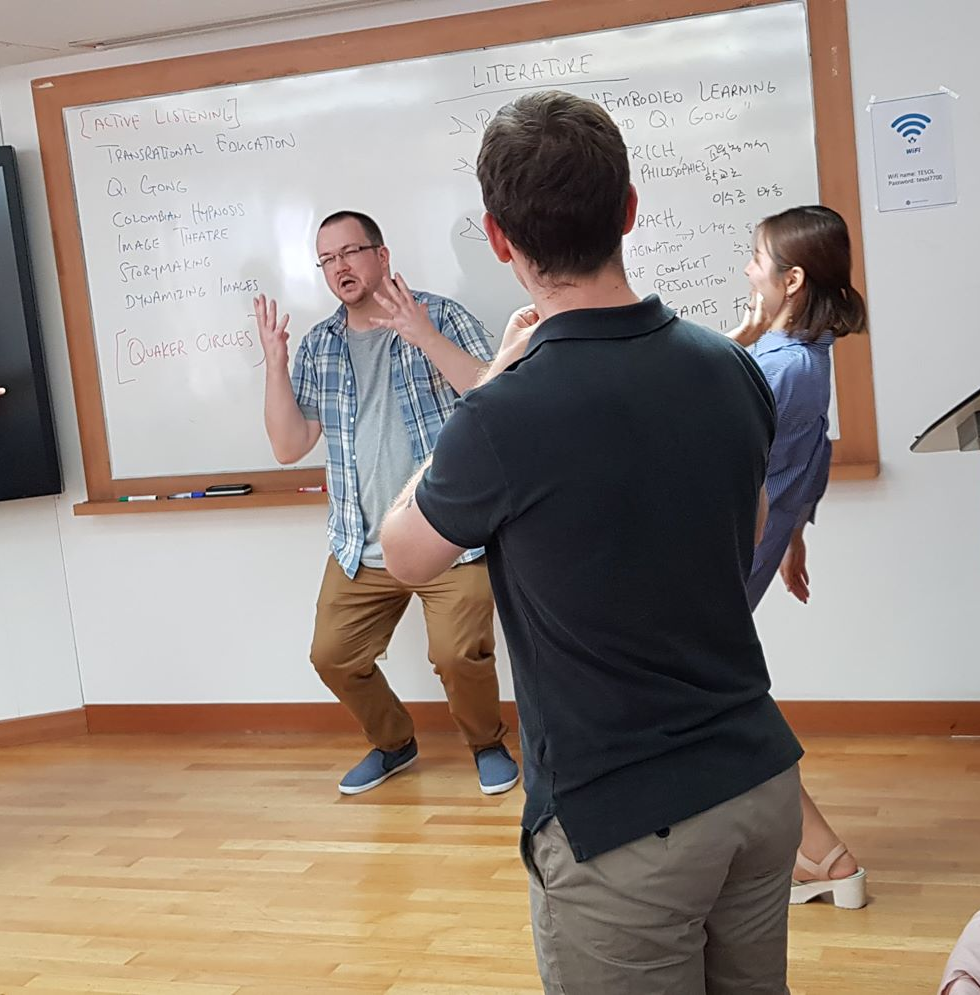

Photographs courtesy of Maria Lisak, Jonathan Moffett, Lindsay Herron, and Bryan Hale.

Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL UPCOMING EVENTS

Check the chapter’s webpages and Facebook group periodically for updates on chapter events and online activities.

For full event details:

Website: http://koreatesol.org/gwangju

Facebook: Gwangju-Jeonnam KOTESOL

The Editor

David Shaffer is an expat educator who has spent two score and seven years in the field of English education in Korea. He has experienced many joys of teaching and living in Korea, but he has also dealt with the challenges they present. As vice-president of the Gwangju-Jeonnam Chapter of KOTESOL, Dr. Shaffer invites you to participate in the teacher development workshops and their regular meetings (in-person and online). He is a past president of KOTESOL, and is currently the chairman of the board at the Gwangju International Center as well as editor-in-chief of the Gwangju News.