Yŏch’ŏn 1996: Returning to My Vanishing Korean Hometown

By Jon Dunbar

My last visit to Yeosu was in January 2019. I visited the 2012 Expo grounds, now virtually empty with a nice aquarium, and then I took a long taxi ride across town to the City Hall area, of which I was most intimately familiar. At Butterfly Island, a brewpub serving some of the best craft beer I’ve ever tasted, I met a Canadian who claimed to be the second-longest-term foreign resident there. He was quite surprised to meet a fellow foreigner whose memory of the city stretched back even further.

Of course, when I first visited, this was part of Yŏch’ŏn (Yeocheon in today’s romanization), which was absorbed into Yeosu in 1998. In 1996, my uncle taught English there, and so my parents sent 16-year-old me and my 14-year-old sister to visit for a month, at the same time as our 12-year-old twin cousins who were visiting their dad.

in the distance.

We landed at what was then called Kimpo International Airport, the country’s main airport, in July in painfully hot, humid weather, and endured a very long van ride cross-country, all the way down to my uncle’s home. We knew we were getting close when we started seeing all sorts of chemical plants everywhere, lit up at night like Christmas.

Korea was a developing country back then – chaotic, construction everywhere, full of bad smells. Korean people were, if anything, kinder and more welcoming to strangers back then. Culturally, it felt geekier than today; I recall a fad at the time being guys wearing their glasses or sunglasses on the back of their heads, for whatever reason. We used to crack up watching “Icing,” a soap opera about a Korean hockey team.

The roads were more dangerous back then, filled with vehicles unfamiliar to us. We were obsessed with Daewoo’s Damas and nicknamed it the “microvan.” Less impressive were the blue pickup trucks, which I nicknamed “psycho trucks.” When my uncle would leave us at home for the day, sometimes one of these trucks would drive slowly through the apartment complex, broadcasting a solemn, eerie message (which years later I learned was just a list of things for sale).

As dangerous as the roads were, jaywalking was rife. Pedestrians would cross wide, busy roads, going one lane at a time, advancing when there was a gap. And it was common to see vendors walking through gridlock traffic, selling treats like bbeongtwi-gi discs to people stuck in their cars. I learned a lot of dangerous ideas watching Koreans jaywalk.

My uncle’s fourth-floor apartment had three bedrooms, and I got my own room. The building showed its age: Lights would flicker like strobes when switched on, and the shower had no pressure at all. And the ceiling was a little lower than you’d expect in a modern apartment.

To keep us busy while he worked, my uncle introduced us to some of his students, including Su-mi and Da-woon, two girls his daughters’ age, and they showed us around as much as possible. But there were no kids my age – they were all studying for the CSAT already. Once, he let me attend a class with his only two 16-year-olds, two teenage girls who were so burned out from studying they could barely keep awake.

Once, Su-mi and Da-woon took us to Yeosu, 30 minutes away. I felt weird following preteens on an intercity bus, but it seemed perfectly normal to everyone here, even my uncle. When I say Yeosu, I mean the port area that’s now been almost all wiped away by the Expo area. We went to a dingy roller rink, walked out over the breakwater to Odong Island, and visited a few markets. At one market, I saw a fishmonger pulling live eels out of the water and butchering them right in front of me. It might have been the first time I witnessed death.

Korea’s now-famous nightlife wasn’t on display back then. It seemed like after dark, Yŏch’ŏn became a ghost town. Once, my uncle’s coworkers brought us to a noraebang, where our inability to take singing serious certainly annoyed the adults. We hung out with adults a few times, either at someone’s home or in front of a convenience store, where we would be served watermelon and popsicles, and sometimes beer. I had my first beer, probably Cass.

Living with my uncle was difficult, and after a shouting match one evening, I ran away. I wandered the streets, but there was nothing to do, nowhere to go. I climbed the highest mountain around, Mount Ansim, pulling myself up over the boulders and weeds, careful to avoid spider webs. There was enough light from the city below that it wasn’t too dark. I stopped eventually on a flat, bare rock, unable to go any higher. Finally, I came down, and at around 3 a.m., I returned to my uncle’s apartment. Rather than go in the front door and wake everybody up since I didn’t have a key, I scaled the outside of the building, climbing from balcony to balcony, a feat that wasn’t so hard due to the shorter distance between floors, and within seconds I was climbing in through my window and jumping into bed.

In front of the apartment building were bins for recycling. Once, on one of our final days there, the four of us grabbed a bunch of plastic bottles and threw them out from my uncle’s window, one by one, trying to hit the bins way down below. For each, we listed a complaint about the country that we wouldn’t miss. “This one’s for all the weird fish and sewage smells!” “This one’s for the humidity!” “This one’s for the psycho trucks!” By the time we finished, a crowd of concerned Koreans had begun to gather in the parking lot below.

We left on August 17, just as a typhoon was approaching and while riot police prepared to clash with students protesting at Yonsei University. It felt like the country was collapsing behind us as we raced for the airport.

The trip was a grueling experience, but after returning to Canada, I couldn’t stop thinking about Korea. I made up my mind to return after graduating university, and sure enough I did.

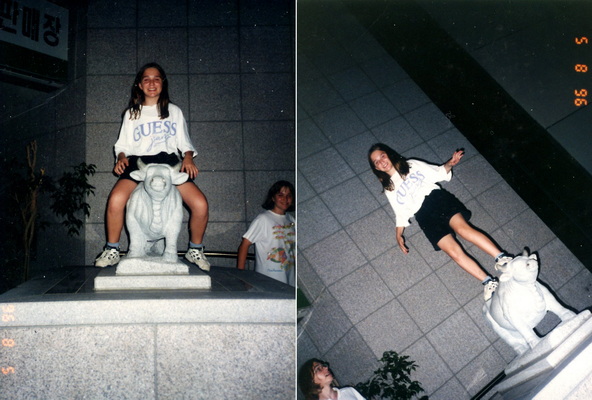

I’ve since been back to Yeosu about four times. In 2009, I visited in time to see the old seaside community being destroyed to make way for the 2012 Expo. And in 2012, I returned with my parents, first to the Expo, but also to show my mom where we’d stayed with her brother. The area has changed since 1996. But traffic still swirls around the rotary in front of City Hall. Nice new buildings stand on the former site of my uncle’s old apartment, but they’re still residential. And the entrance to the Hanaro Mart down the street is still flanked by two cow statues that I remembered playing around on with my sister and cousins over two decades earlier. The city may not look exactly the same anymore, but it still feels like my Korean hometown.

The Author

Jon Dunbar first visited Korea in 1996 and moved back permanently in 2003. He is general editor of the Royal Asiatic Society Korea journal Transactions, a self-published author, and a copy editor at The Korea Times. He has also been contributing the Gwangju News crossword since June 2019.