Odds and (Dead) Ends: The Third Coming

Written and photographed by Isaiah Winters.

Welcome to another wholesale liquidation of the half-baked rejects and lowbrow minutiae cluttering my workspace these last six months. In this edition, we’ll first look at the latest doomsday dictum from Gwangju’s one-and-only Heavenly Father™. Next, we’ll observe English’s longstanding role as a language of love for Gwangju’s lads on the down-low, and then bringing up the rear is a much-needed installation that abridges suicide in the City of Light. So, stow your trays and get ready for another uncomfortable ride.

When Your Preferred Pronoun is “God”

As you’ll recall, Choi “Heavenly Father” Ban-ok is Yang-dong’s self-proclaimed messiah, and every so often he comes out with a new business card that reads like the Book of Revelation. Distributed freely from a card holder on his front door, I like to stop by every few months and catch up on his latest pocket-sized prophesies. As of my last visit in mid-October, he’s updated his rapture message, gotten a makeover, and newly festooned his home to accommodate a recent uptick in visitors.

Basically, Heavenly Father’s scheme is to convince as many people as possible to register their names at a rural address he owns, which is where he’ll recreate heaven, or something. (How he’d actually profit from this is a mystery that’s captivated me for some time.) According to his latest card, heaven has apparently moved from a tiny rice field along the coast of Yeonggwang-gun to one of the nice little islands off the coast, so things seem to be looking up for him. For those of you who didn’t join his cult on the ground floor like I did, we rejoice in your lamentations.

Aesthetically, his new card is more stylish than ever. I admit I felt American Psycho-like card envy when seeing its backside, which now bears his full-body portrait. Sporting a sleek, buzzed head reminiscent of Charles Manson’s later years, Heavenly Father no longer dons the bold, red robes of his past. His attire of choice today is a refulgent space hanbok of shiny silver and white. The way it sparkles over badly photoshopped blue skies and cottony clouds is simply paradisiacal. Tastefully, the only splash of color in his countenance is the word cheonbu (천부, Heavenly Father) tattooed in red across his forehead. With a mark like that, what more needs to be said?

In terms of his latest apocalypse message, there’s nothing much new. He still controls the world’s doomsday clock and implores you to register at his new address in order to enter heaven. If you don’t, heaven will forever remain cordoned off. Since I’m already a member, I honestly find the warning sign posted on his front door far more interesting. It asks visitors not to knock, but instead to call out to Heavenly Father when seeking entry. As a stern coda, it says those who enter without Heavenly Father’s permission are subject to censure by heavenly decree. When you take all the recent changes together – the stack of new white shoes out front, the updated cards, and the new makeover – it suggests that the house has been seeing an increase in visitors over the last six months. I wish the cult well.

English: The Language of Disparate Lovers

I’ve long believed that English, more than any other living tongue on Earth, is the undisputed language of love for disparate peoples. Of course, it’s not the sound, rhythm, or romanticism of English that makes it so. Instead, it’s the sheer number of both native and non-native speakers that allows more people of various unrelated backgrounds to randomly hook up than any other language. Pair up any two people with different mother tongues anywhere in the world over and over again and, most likely, English will emerge as the dominant enabler of intercourse.

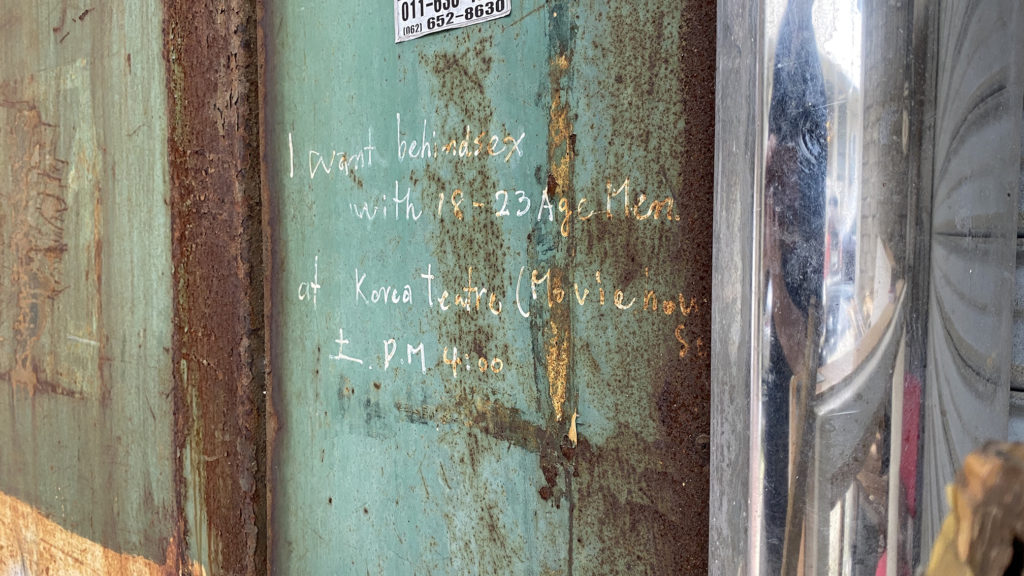

An example of this is etched on the wall of a seedy back alley between Geumnam-ro and Daein Market. Not far from a string of sex shops and senior-citizen dance clubs known as colatheques (콜라텍) is a sort of pre-internet Grindr profile for someone seeking “behindsex” at “Korea teatre” on “土,” (토 / to, Saturday) at 4:00 p.m. The specific spelling, capitalization, and lexicon used all offer insightful hints at who might have etched this enduring public service announcement. As your humble linguistic confidant, I’ve spent innumerable late nights wrapping my head around this longstanding enigma and have come to certain dispassionate conclusions.

Of course, “behindsex” isn’t the native English-speaking nomenclature, while “18–23 Age Men” uses rather unorthodox grammar, punctuation, and capitalization. Furthermore, the use of hanja (Chinese characters) to mark the day of the week is quite telling. Also of particular interest is the spelling of “teatre” which, after a lot of late-night Googling (for research purposes, of course), links strongly to a few different theater venues in Barcelona, Spain. This could be because Spanish is likely the second-most common language spoken among lovers of disparate mother tongues, or maybe he was just sounding out “theater” in his head and, lacking a dictionary, came up with this unique spelling.

Ultimately, if I had to guess the background of this proto-Grindr graffiti artist, I’d say he’s an older Korean male who’s learned a fair amount of English in life and maybe traveled to Europe a bit. If I had to venture an alternative guess, I’d say he was a transient European who loved going downtown for anonymous romps on weekends. (Note: In preparation for this article, I spent an entire Saturday afternoon in front of Gwangju Theater looking blissfully available but sadly failed to establish any liaisons. Maybe it was my age.) As they say, more research is required, I guess.

Bridging the Gap

Exactly two years ago, Lost in Gwangju covered the tragic beauty of Nam-gu’s Cloud Bridge, a 37-meter-high pedestrian overpass spanning a narrow valley along the ridge of Jeseok-san in Bongseon-dong. The bridge has unfortunately been the site of many suicides, including two in 2017 that took place on the same day. The victims were lovers in their twenties, one of whom was a young man suffering from mental and financial difficulties and the other a young woman who couldn’t stand to go on alone in his wake. A year and a half after that article was published, the bridge was given a significant safety facelift that ironically created an entirely new crisis.

During a revisit to the bridge last spring, I was surprised to find that a forest fire had scorched much of the nearby mountainside. Even more surprising was the fact that the bridge’s safety railing had very recently been reinforced and topped with a spinning anti-suicide bar. After doing a little research, it turned out that while workers were cutting and welding the railing for the new safety installment, the nearby hillside caught fire, likely from sparks flying down onto the dry vegetation. Luckily, the fire was extinguished in about an hour and no one was injured.

Whereas the railing was previously only about chest high, now it towers above most people’s heads and curves inward, making it much harder to climb. The spinning top bar works a lot like beads on an abacus, with little spinning discs lining the bar’s entirety and making it hard to get a grip on the top rung. It’s an ingenious addition that has almost no effect on the stellar view and maintains the original aesthetic of the bridge. I’ve got nothing but praise for whoever proposed that fix and highly recommend you visit the bridge to enjoy both its beauty and ingenuity.

There you have it, dear readers. I hope you’ve enjoyed the third coming of Odds and (Dead) Ends. Whether you’re in search of an up-and-coming cult, weekend passion, or a new lease on life, Lost in Gwangju’s got you covered.

The Author

Originally from Southern California, Isaiah Winters is a Gwangju-based urban explorer who enjoys writing about the City of Light’s lesser-known quarters. When he’s not roaming the streets and writing about his experiences, he’s usually working or fulfilling his duties as the Gwangju News’ heavily caffeinated chief proofreader.