Unhealed Light: Drawing Inspiration from Kim Eun-ju’s 5.18 Photography

By Isaiah Winters

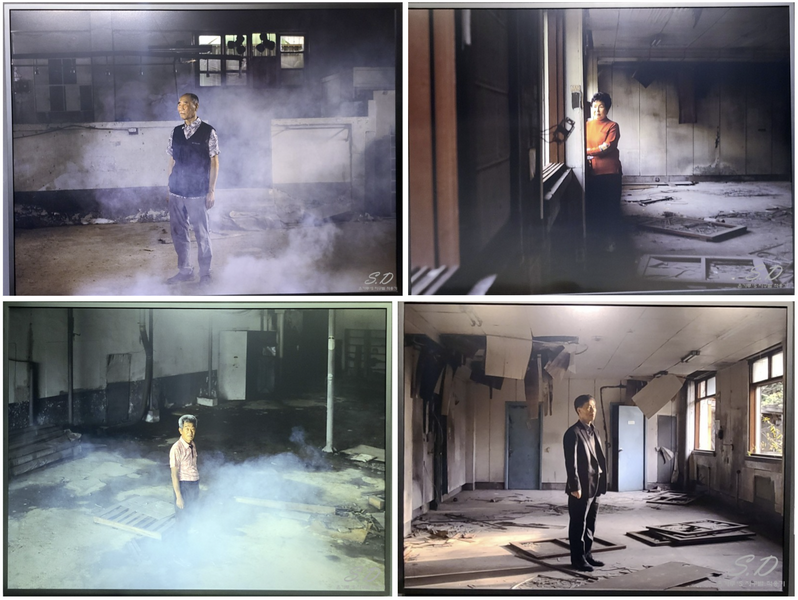

Last year’s Gwangju Design Biennale left an indelible impression on me. In my view, its best exhibit featured haunting photos of 5.18 survivors standing in the very places where they’d suffered trauma during the city’s democratic uprising over 40 years ago. Since seeing those photos, I’ve been unable to get them out of my head. It’ll come as no surprise to readers that I’d already had a deep interest in photographing the same sites, but seeing another photographer’s poignant imagery from within them was highly motivating and set me on a course to dig deeper. That motivation led me to photograph the old Gwangju Prison earlier this year and the site featured in this month’s article: the former Armed Forces Gwangju Hospital in Hwajeong-dong. What follows is a brief article on the inspirational work of documentary photographer Kim Eun-ju and my recent experience inside said hospital.

Kim Eun-ju has spent many years behind the lens capturing images not only of first-hand survivors and the bereft of the Gwangju Uprising, but also of the Jeju Uprising and the Dirty War of Argentina. Some of her main themes naturally include popular uprisings, civilian massacres, and the unhealed wounds they leave, often on the hearts of bereaved mothers. For her first solo exhibition in 2011, Kim’s “Here, Here…” (여기, 여기…)1 featured traumatized mothers of the Gwangju Uprising years later at the very sites where they’d suffered. By uniting modest people with the locations of extraordinary events in this way, Kim was able to provoke an intense level of empathy for common people that would’ve otherwise been lost on most observers. This kind of sober reunion is something I’ve long been fascinated with in my own work: Finding forgotten pictures of people as they were in their now-abandoned homes is still my greatest thrill as a novice photographer.

As for the Design Biennale photos that sparked my interest, Kim in her exhibition description found deeper meaning in our city’s name – Gwangju, the City of Light – that applies to unhealed wounds at various stages of exposure.2 The victims of 5.18 are shown only partially lit in living historical sites like the former Armed Forces Gwangju Hospital, implying that these first-hand witnesses are still very much with us, though social currents have long obscured their presence to varying degrees. What I gather from the description is that although the city has taken up the mantle of human rights with the Gwangju Uprising as its core emblem, the ruined buildings and lives we still see today are far from healed. This helps explain the exhibition’s full title: “Unhealed Light Peering from a Black Room” (금은 방에서 들여다보는 치유되지 않은 빛). All this may sound rather critical, but the opening line of the description said it best: “Gwangju is still a work in progress.”

To be sure, in my comparatively short time photographing a few of the darkest sites related to the Gwangju Uprising, there’s been noticeable progress. For example, the former 505 Security Forces’ Headquarters in Ssangchon-dong is midway through a long restoration process that’s turning the notorious torture site into a historically significant public park. Meanwhile, the city has taken over other sites such as the old Gwangju Prison in Munheung-dong and the Red Cross Hospital downtown with plans to turn them into living history sites of some sort for the public. In addition, the former Armed Forces Gwangju Hospital featured in this article has already long been open to the public as an expansive green space for those seeking a little exercise, some 5.18 history, and – for a few of the renegade elderly – a place to start a hobby farm contrary to the city’s wishes.

My experience with the latter site goes back a few years, but only recently have a few of its lesser-known structures become accessible. In particular, a barracks where soldiers used to bunk, study, and wash up provided a few unique photo opportunities worth sharing. Most intriguing within the barracks was the armory, where various arms were once secured behind multiple gates and padlocks. These included M16 rifles with bayonets and sheaths and .45 caliber M1911s, all of which were painstakingly tallied in black marker on a laminated status board. The arms are all gone now, of course, though the gates have been left wide open, presumably since May 16, 2009, the last date written on the board. I found it interesting that the site closed then, almost as if in preparation for the 29th anniversary of 5.18 that year.

Nearby the barracks is the main hospital building. Connecting all seven of its wings is a long central corridor that reminded me very much of the layout at Gwangju Prison. Though this elongated hallway would’ve made for great photos, its slew of motion detectors had me looking elsewhere fast. I soon ended up in one of the many wings, weaving between gravity-laden roof panels and piles of shattered windowpanes with only a few underwhelming shots to show for it. I’d shot large, empty indoor spaces like these many times before, but they’re the kinds of places that often look better through your eyes than a lens. Kim, on the other hand, was able to turn these same desolate hospital wings into rather dramatic backdrops for her photo subjects – a testament to her excellent eye for lighting and positioning. I guess I’ll have to keep taking notes while drawing inspiration from her amazing work.

Sources

1 Pyeon, S. (2011, May 3). 5․18희생 어머니를 그린 ‘여기, 여기 …’, 사진작가 김은주씨. 시민의 소리. http://www.siminsori.com/news/articleView.html?idxno=64963

2 wella5442. (2021, September 6). 광주 디자인비엔날레 디-레볼루션. 은가루‘s 지구별 적응기. https://blog.naver.com/wella5442/222496979233

The Author

Born and raised in Chino, California, Isaiah Winters is a pixel-stained wretch who loves writing about Gwangju and Honam, warts and all. He particularly likes doing unsolicited appraisals of abandoned Korean properties, a remnant of his time working as an appraiser back home. You can find much of his photography on Instagram @d.p.r.kwangju.