Peeling Through the Past

By Isaiah Winters

I never cared about wallpaper – until now. That’s because on a recent revisit to one of Gwangju’s oldest abandoned hanok houses, a friend showed me just how much history can lurk between the layers. In this month’s edition of “Lost,” I return to Imgok-dong with hanok restorer and now avid wallpaper collector Kang Dong-su to literally peel back the layers of history, exposing evidence of colonialism, affluence, and unique bits of minutiae along the way. If I somehow manage to make wallpaper analysis seem interesting in the process, then I’ll chalk it up as a win for the column.

Creaking Cosmopolitanism

In this section, I’ll provide a historical framework for the hanok itself, backed by Dong-su’s many insights. Basically, the hanok’s imposing exterior bears design motifs that draw inspiration from across the globe and bookend Korea’s colonial period. While its overall structure is naturally Korean, the main pillars’ narrow-to-wide shape suggests repurposed pieces of the house may date back as far as the late-Joseon era. Another telling detail is seen in a patio extension on the south side, which is neatly lined with narrow floorboards and wood notches atypical of hanok. That’s because they’re of a Japanese design Koreans call jangmaru (장마루) and date back to the occupation era. Interestingly, the front patio facing west retains wider, juxtaposed floorboards more typical of hanok, a floor design known as umulmaru (우물마루).

In addition to these features, high above the Japanese occupation-era porch extension is a brick gable whose influence may date back to when Christian missionaries arrived around the turn of the 20th century, bringing brickwork construction along with their religion. Sitting above the gable are mass-produced concrete tiles, likely added in the 1960s or 1970s, which were made in Korea but retained a Japanese style, as the tile-making facilities of the day were inherited from the colonial era. The most mysterious piece of the hanok by far is a single wood panel used in the kitchen’s construction. Taken from an old wooden crate, it’s originally part of a petroleum shipping box produced by Atlantic Petroleum, headquartered in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. One online source dates this sort of crate to 1907, but how it became part of a rural Gwangju hanok is anyone’s guess. Given all this, the house, despite its decrepit state today, was remarkably cosmopolitan for its time.

Peeling Through Time

Bland, beige, and blanketed with dust, the latest wallpaper inside the hanok leaves little to the imagination. However, in just a few short minutes, Dong-su was able to find enough of interest to inspire an article of its own. A humble split in the first door we came to revealed large panels inked with hanja (Chinese characters), which seemed to have been used for writing practice before being entombed within the door. Beyond the door, just under a loose flap of wallpaper, were large sheets of delicate paper bearing extensive missives in beautifully written Hangeul. A small tear beside a window frame unveiled a timeworn Japanese newspaper with playful fonts and old-timey illustrations, and another dog-eared strip found elsewhere exposed a pattern that, according to Dong-su, still exists in Changdeokgung Palace up in Seoul. This was all discovered in about 15 minutes beneath maybe one or two percent of the hanok’s total wallpaper – and in just a single wing.

Once back in the hanok’s centermost room, we both leaned in to analyze another Japanese newspaper glued to a beam beneath a shelf when Dong-su suddenly shrank by half a meter. The rotten floorboards had given out beneath him, something he said happened quite often. Though we laughed it off, it was a startling reminder that our mutual hobby came with as many risks as rewards. Moving on to the most exposed and weather-beaten room in the house, I didn’t expect to find much, but I was dead wrong. Years of constant rain, wind, and collapse had created a conveniently layered wallpaper flap of three or four plies spanning an entire wall. Some plies were so well separated that it was like flipping through samples in a wallpaper catalogue. Here we found more hanja practice scribbles and a large wallpaper pattern Dong-su had seen in a hanok from the 1940s up in Incheon. Though much of the wallpaper’s color and luster are now gone, its bold pattern still retains an air of status and respectability.

Miscellaneous Conjecture

Unfortunately, the current owner can’t shed much light on the hanok’s origins, though he’s happy to have two young-ish men visit and haul away some of the peeling garbage for him. If I didn’t feel like such a tax on his patience, I’d honestly love to spend an entire week revisiting the house and nerding out on all the documents and heirlooms left inside. On each visit, I try to lessen the annoyance by bringing a gift – a bottle of Jindo hongju last time, and two bottles of makgeolli this time – but I still feel like a nuisance. Risking overkill but nursing a paucity of facts, I’m left to guess the original owners’ source of wealth, their status in the local community, and the sudden dispersal of them all from such a priceless family treasure. If I had to wager a guess, maybe they were involved with whatever passed in and out of the now–shuttered Imgok Station; maybe they had connections to the gold mine at nearby Yongjin-san; or maybe they were land barons along this extremely fertile stretch of the Hwangnyong-gang. It’s hard to say.

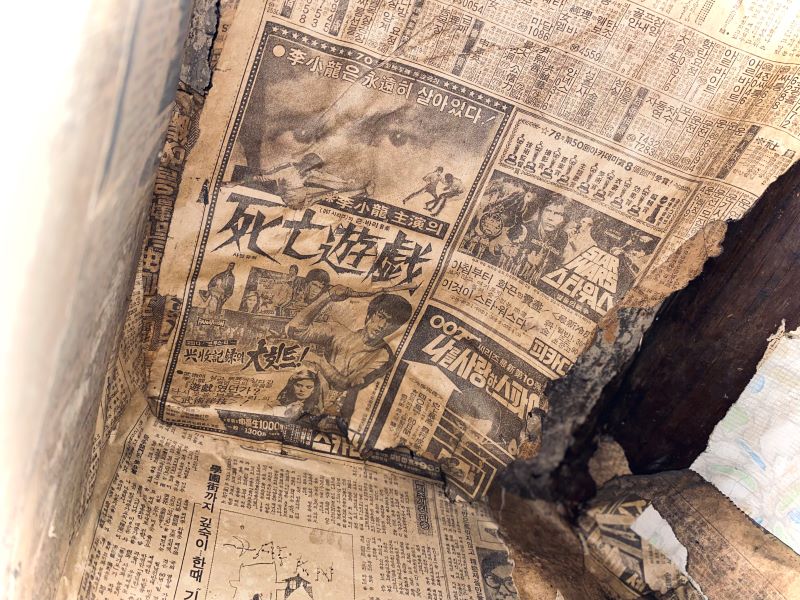

To finish off this little section on naked conjecture, I’ll provide the last of my lowbrow, low-resolution thoughts on what else I found interesting about this particular hanok. While Dong-su was busy uncovering wallpaper that linked the moldering dwelling to the centers of power in Seoul, I found one tiny pop-culture reference in the corner of a nondescript storage closet to be very intriguing. There, I saw a single corner of an old newspaper advertising three classic films: Bruce Lee’s Game of Death, 007’s The Spy Who Loved Me, and the original Star Wars film. This suggests the newspaper is from 1978 which, though half the age of some of the relics seen elsewhere in the hanok, still makes it a 45-year-old rag marking a monumental year in filmmaking. According to its fine print, an adult ticket back then was 1,300 won, while kids or anyone catching a flick in the morning got in for a mere 900 won. Loving little discoveries like this, I wish I had more time to comb through the hanok’s many other recesses. Maybe it’s time for another visit – this time with some plum wine.

Kang Dong-su’s Instagram: @baemui.naru

The Author

Hailing from Chino, California, Isaiah Winters is a pixel-stained wretch who loves writing about Gwangju and Honam, warts and all. He’s grateful to have written for the Gwangju News for over five years. More of his unique finds can be seen on Instagram @d.p.r.kwangju and YouTube at Lost in Honam.