The Soil Has Brought Us Up: The Artist Couple of the Baegun Kiln

By Kang “Jennis” Hyunsuk

In Gwangyang, Jeollanam-do, there is a high mountain named Baegun. It is facing Jiri Mountain across the Seomjin River. At the foot of Baegun Mountain, you will find a traditional kiln named Baegun, where buncheong ware is fired, expressing the unique color of the soil. The Baegun Kiln (백운요) has been operated for over 20 years by an artist couple. When I followed the sign announcing the name of the kiln, I spotted cute clay sculptures hiding among the flowers in the garden. This made me feel as if I were entering a fairy world. For this month’s People in the Arts, I met with Kim Jeong-tae and Shin Hyo-jung, the artist couple of the Baegun Kiln.

While the ceramist, Kim Jung-tae, was working in his studio, I started the interview with the sculptor, Shin Hyo-jung, who focuses on clay sculptures.

The Shin Hyo-jung Interview

Jennis: It’s an honor to meet you. I heard that you are preparing for the firing process of the kiln soon. So thank you so much for taking the time for this interview for the Gwangju News.

Shin Hyo-jung: Thank you for coming all this way.

Jennis: The handwriting on the wall is touching: “The soil has made me.” Can I ask who wrote this?

Shin Hyo-jung: I learned calligraphy from my grandfather when I was young, and I enjoyed writing calligraphy. When I was in a calligraphy club in my high school days, I won first prize in the national calligraphy competition. So people said that I had manual dexterity. A few years ago, my husband asked me to write the phrase on the wall. He had previously thought that he made bowls with soil, but through living in the process of working with soil, he came to realize that it was the soil that has made him humble.

Jennis: I wonder how the two of you met and have worked together with the soil.

Shin Hyo-jung: My husband is a friend of my older brother. He was a very diligent young man, so my mother wanted to take him as her son-in-law. After we got married, we sometimes went to my uncle’s to help him with his work. My uncle, Jeong Woong-gi, is a ceramicist who has operated the Hadong kiln in the pottery village of Hadong. My husband, who fell in love with my uncle’s beautiful works, asked my uncle to accept him as his apprentice. But my uncle told him to think it over because living as a ceramist is not easy. Anyway, my husband got permission through his earnest requests. And when we settled down here, my uncle came in person and named the kiln “Baegun.” It has already been over 20 years since we first fired the Baeun Kiln.

Jennis: How did you come to make clay sculptures, and what do you consider to be the charm in your work?

Shin Hyo-jung: I suddenly felt that I wanted to express my own feelings when I made pottery as a hobby. But it is not easy to express one’s feelings with a bowl. When I make clay sculptures, I feel calm without really realizing it. So I love to work with clay sculptures – they make me smile.

Jennis: I heard that buncheong ware is baked in a traditional wood kiln, so do you bake your clay sculptures in the same kiln?

Shin Hyo-jung: Oh, no, clay sculptures can’t be baked in a wood kiln. I tried it once, but the temperature of the kiln was too high for clay sculptures. I want to express bright feelings through my clay sculptures, so a wood kiln doesn’t suit my work. I bake my clay sculptures in a gas kiln at a slightly lower temperature than that needed for buncheong ware.

Jennis: I think it would be heartbreaking if the works that took many days to make melted or broke in the baking process. It must have taken a lot of time to find the proper temperature for baking.

Shin Hyo-jung: Yes, it did. The heating process is quite delicate, so it took me a lot of time to find the right temperature.

Jennis: The clay sculptures you make are called to-u (토우) in Korean, meaning “clay friend.” What gratification do you get out of making so many clay friends?

Shin Hyo-jung: I want to put my heart and soul into creating each clay sculpture. So I cannot make a lot of “friends” at once. If I feel uncomfortable or uneasy for whatever reason, I cannot work. So if something uncomfortable occurs, I quickly purge it from my mind.

Jennis: Thank you, I think it’s now time for your husband’s part of the interview. My hope is for you to always be in a very good mood so that you are able to create many more of your little “clay friends.”

The Kim Jeong-tae Interview

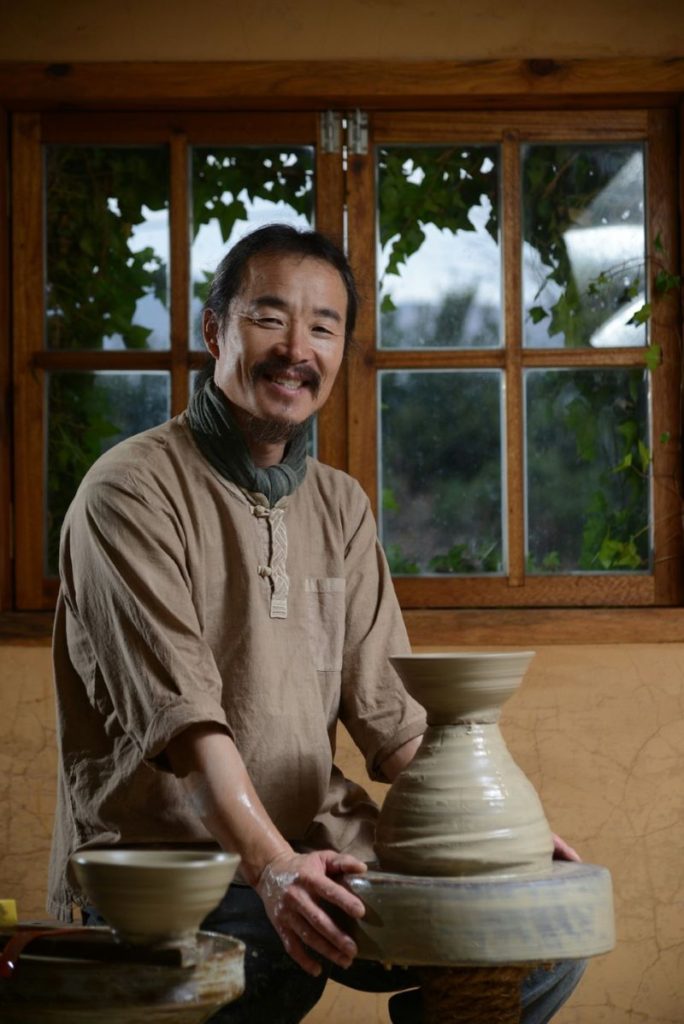

After listening to the story of the clay sculptures that purify the heart of artist Shin Hyo-jung, I moved to ceramist Kim Jung-tae’s studio and continued my interviewing. In his studio, bowls made from the potter’s wheel were waiting for the artist’s next touch as they dried out their moisture. On the desk, books related to pottery were showing his daily life focused on buncheong ware.

Jennis: As a tea lover, I’m interested in tea bowls. I heard that buncheong pottery has been loved by many a tea lover. So, I’ve been quite interested in buncheong ware and would like to learn more about it from the one who makes it in the traditional kiln named “Baegun-yo.”

Kim Jeong-tae: “Buncheong earthenware” (분창사기) is an abbreviation of “Bunjang-hoecheong earthenware” (분정회창사기, grayish-blue pottery coated in white slip). It appeared between the celadon of the Goryeo Dynasty and the white porcelain of the Joseon Dynasty. The pottery pieces are first heated to 850 degrees Celsius, coated with white clay water, and then coated again in one of several ways.

Some of the more common ways of coating buncheong are brushing on white slip with a thick brush, etching in designs to reveal the dark soil beneath, scraping away the background of the pattern, or drawing images or designs with a brush using iron-rich paint. But the easiest method of coating is by immersing the bowls in white clay water and soaking.

Jennis: Among the many ways of making buncheong, which technique do you most commonly use?

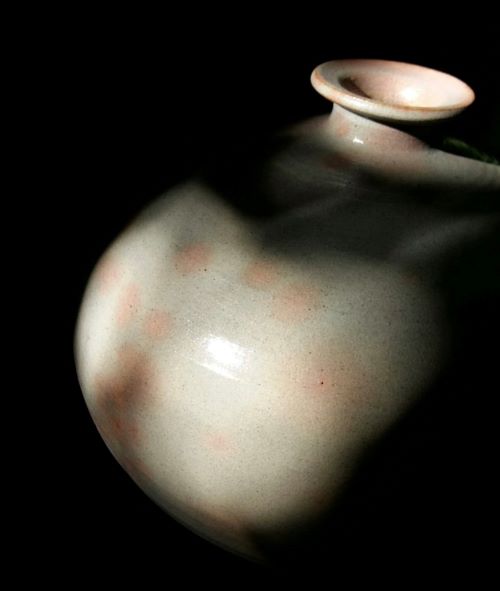

Kim Jeong-tae: The characteristic of my work is spreading colors onto a piece of pottery and seeing them bloom like flowers when the fire meets the soil in the wood kiln. I like this natural change, often creating unexpected colors. Also, like the inlay technique of Goryeo celadon, I am using this technique with a wide variety of stamps to make impressions on my buncheong works.

Jennis: How is a bowl baked in a traditional wood kiln different from one baked in a kiln using electricity or gas? And it is said that there are several ways of heating in a traditional kiln. Can I ask what they are?

Kim Jeong-tae: Unlike gas and electric kilns for which it is easy to control the heat, it is difficult to control the temperature in a traditional kiln. But the color change that occurs on the bowl depending on the type of soil, the type of glaze, the firewood, the strength of the wind, and the method of feeding the fire – this color-change magic occurs only in the traditional wood kiln.

A day before the main firing up of the kiln, I preheat the kiln to blow out the moisture. I usually use oak and pine as firewood. I use one of three heating methods: oxidation, reduction, and neutrality. Among them, I usually use neutrality for my buncheong ware. When finished, I slowly cool down the kiln and then take the pieces out.

Jennis: You must be very nervous when you light a kiln. Staying up all night, observing the color of the flame moment by moment, and deciding which firewood to put in must take fortitude.

Kim Jeong-tae: Yes, that’s right. Because the fate of the pottery pieces that I’ve been working on for many months is decided by the kiln in a single day. So, before I fire the kiln, I place a bowl of clean water in the kiln to express gratitude to the potters who had lived on this earth before me, and then I start working. When the fire goes out, the water in the bowl has disappeared, so I believe that the gods of the potters consumed it well.

Jennis: I’m also curious about how to obtain and store the soil, which is the main material for your works.

Kim Jeong-tae: I look for a site where construction has cut into the side of a hill to save good soil. I’m curious about what colors will result in the finished pieces from the stones or soils that I have gathered. I grind the stones and soil finely, and then I put them in water and stir. The soil sinks to the bottom and the dirt floats. This process is called subi (수비). After filtering with fine nets several times, the fine soil is put out to dry in the shade. When it’s dry, I put it in a sack for months to mature. The soil, which is aging in the sack, is mixed with five or six different types of soil when I make the clay dough for a piece of pottery. When kneading the soil, I should remove as much air from the dough as possible. If the air is left in the clay dough, the air expands in the kiln and the bowl breaks when it is baked.

Jennis: What do you think are the special characteristics of the Baegun Kiln?

Kim Jeong-tae: I make pottery from soil, but when I put into the kiln these pieces that I have worked on for months, there is a moment when I can’t control myself as a human. Once, I got no usable pieces of work from an entire kiln firing. When I take out a well-baked piece, I can see its pink patterns blooming like a sunset. People call it “kiln magic” or “kiln change.” The various minerals in the soil bloom on the earthenware piece like the Milky Way in the night sky, or like plum blossoms, or the autumn leaves of a persimmon tree. So I think that a piece of pottery is a combined work of art that results when the ceramist meets with the soil, the wind, the air, and wood. And I humbly accept the limitation of human abilities. If there is a special characteristic of the Baegun Kiln, I think it is to find the original color of the soil.

Jennis: I appreciate your time. And thank you for giving me the opportunity to make a bowl by myself. Feeling the soil in my hands was a touching experience. Since you provide experience activities in making pottery and clay sculptures for the students who live nearby, I feel your desire to convey the beauty of soil to the next generation. Thank you.

After the Interview…

After the interview, I returned home and did some additional research on buncheong ware. It is said that buncheong ware gradually declined in the late 16th century but was abruptly ended by the Japanese invasions (Imjin-waeran, 1592–1598). After the war, many Joseon potters made pottery in Japan, and their works were exported to Europe under the name of Japan. According to Kurokami Shutendo, who wrote the biography of Lee Sam-pyeong, a potter who was taken to Japan during the war and became the Kamisama of the Arita Kiln, there were 30,000 Joseon potters who were forcibly taken to Japan at that time.

The Author/Interviewer

Jennis Kang is a lifelong resident of Gwangju. She has been doing oil painting for almost a decade, and she has learned that there are a lot of fabulous artists in this City of Art. As a freelance interpreter and translator, her desire is to introduce these wonderful artists to the world. Instagram: @jenniskang