The Han in “Hanguk” : The Naming of South Korea

Our previous article in Blast from the Past (March 2022) discussed Korean han, referring to a sort of deep regret. This month’s article discusses another han, the “han” in the Korean name of South Korea: Hanguk. Is “han” a Chinese loanword? Is it unique to Korean? Why was it selected for the name of South Korea? Why do Koreans put so much meaning into this han? Answers to these questions can be found in the following article originally appearing in the March 2015 issue of the Gwangju News as “What’s in a Name?” and penned by Adam Volle, who also wrote the earlier han article. — Ed.

There’s an oddity in the names of countries that you may not have thought about before. When Germany was formally split into two separate nations in 1949, the respective new governments naturally took on different names for their nations: the Federal Republic of Germany was the name taken by West Germany, while East Germany became the German Democratic Republic. Similarly, the division of Vietnam into two countries from 1954 to 1975 resulted in the rise of a northern regime creating the nation called the Democratic Republic of Vietnam and a southern regime naming its newly created nation the Republic of Vietnam. Both nations have “Vietnam” in their names, as was the case for divided Germany. And if you read the official English titles of North and South Korea (Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and Republic of Korea, respectively), you might think that the two Koreas have followed this same Cold War-era naming convention.

When the official names of the two Koreas are read in Korean, a curious disparity pops up: Each country has a different name, and neither uses the word “Korea.”

It was the Korean communists in the north who made the natural choice, in 1948, of referring to their nation as “Joseon” (조선) when asked by the Russians what democratic republic they would be. “Joseon,” after all, had been the name of the land for most of the previous 543 years (and if you believed the ancient myths, even earlier than that). The official name for North Korea in Korean became “Joseon-minju-juui-inmin-gonghwaguk” (조선민주주의인민공화국; literally, “Joseon democratic people’s republic”). As an aside, the name “Korea” comes from “Koryeo” (고려), the name of the 500-year dynasty that preceded Joseon.

The new president in the south at the time, Rhee Syngman, offered a different word from “Joseon” for his newly formed country, when he proclaimed South Korea’s first republic “Hanguk” (한국; lit., “the country of the Han”). The full name of this republic would become “Daehan Minguk” (대한민국; lit., “the Republic of the great Han people”).

This wasn’t a big surprise either. In choosing “Daehan Minguk,” President Rhee and the National Assembly were only preserving the name under which Korean freedom fighters had fought their Japanese colonizers for 25 years. The freedom fighters, in turn, had derived their moniker from “Daehan Jeguk” (대한제국; “the Empire of the Great Han People”) because that happened to be the name that the very last king of “Joseon” gave to his kingdom when he abruptly declared it to be an empire and promoted himself to emperor.

That was a surprise. Mind you, Emperor Gojong’s heart was in the right place. The change reflected his overall effort at rebranding his dirt-poor kingdom as a modern nation-state in the high hope that Japan would think twice about gobbling it up in their colonialization of East and Southeast Asia. He even bought stylish Western outfits for everybody. Sadly, the plan didn’t work; Japan simply decided to devour faster, annexing the peninsula in 1910.

Yet the Emperor’s spirit has this consolation: He may be remembered far less for failing to continue one of the world’s oldest dynasties than for gifting his country with a wonderfully appropriate sobriquet that it may wear forever – Hanguk.

True, on a surface level “the country of the Han people” seems an uninspired choice for the name of… well… a country full of people who’ve historically called themselves “the Han.” It was synonymous with, for example, renaming Israel as “the Country of the Jews.” But the emperor’s placement of his subjects’ name on the national marquee was, in itself, a revolutionary and empowering act, an acknowledgement of their stake in his state – and regardless, “han” is far more than a mere label of an ethnic group.

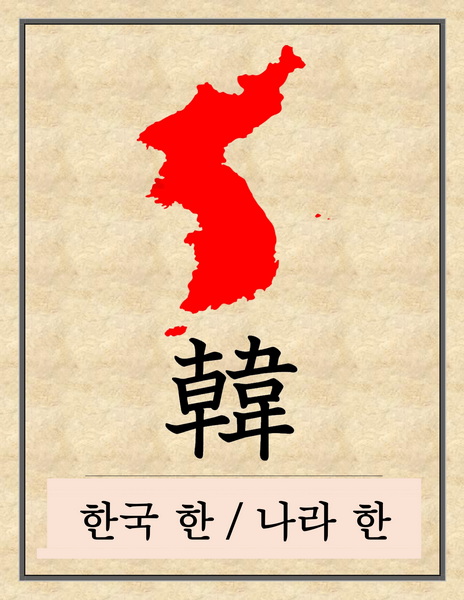

In addition to being used in naming countries on the peninsula from ancient times (Ma-han, Jin-han) and being a Korean surname (both of which use the Chinese character 韓), “han” can also mean “great/huge” and even “leader.” Although the word was first written in Chinese characters and the Chinese also call themselves “the Han people” (but using a different Chinese character: 漢), some scholars contend that the Korean “han” (韓) is not a loan from Chinese. Korean may have inherited the word from its Altaic ancestors, from whom Mongolian has also descended. In fact, the word “han” is a Sino-Korean cognate of the famous “khan” (as in “Genghis Khan”), and “han” (韓) has been used in the names of ancient countries in both Korea and China.

In addition, Korean has the native Korean word hana (하나) for the number “one,” and its adjective form is also han (한). Consider how “being first” is identified with leadership in every culture (e.g., our “first” ladies) and you’ll understand why there likely is a phonetic connection.

More importantly, though, the word “han” (from a different Chinese character: 恨) is also used by Koreans to describe a particular emotional burden that they believe is endemic in Korean culture, even synonymous with it. It has no direct English equivalent, but it’s essentially a deep regret for a terrible loss, whether incurred by duty or disaster. For example, a Korean man’s decision to marry the woman his parents want for him rather than the woman he loves may create this han – so too might be the crushing poverty many Koreans once fought off to survive. [See Blast from the Past, March 2022.]

It’s slightly more complicated than this, though. Central to the idea of this han (恨) is a lack of reconciliation to the pain. It’s nothing like a vague, immature belief that everything will somehow be right in the end, nor is it a desire to actively seek justice. It’s just a grim conviction not to resign oneself to what has happened, to never acquiesce in one’s heart to whatever evil one is otherwise helpless to resist.

This has proven a valuable national trait for Koreans in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. Since Emperor Gojong’s failed attempt to save the homeland, Koreans have endured 38 years of foreign rule, a terrible civil war, and 60 more years of division, with half their people trapped in a communist dystopia. It is almost as if the old ruler had realized the inevitability of his defeat and renamed his lost country as a future reminder to its subjects of whom they must be: a nation capable of enduring such misfortunes but never accepting them. Intentionally or otherwise, South Korea has preserved this message in its name and language ever since, and a hundred years after they were last independent and whole, the Han (韓) retain their han (恨).

Arranged by David Shaffer.