Korean and Tamil Cultural Similarities

Written by Bala Krishnan Ganesan.

Hi this is Bala – a not-so-nerdy freshman PhD student from India, specifically, Tamil Nadu. The reason for being specific about my state is that in India, we Indians are so different in each state but proud to have unity in diversity. For example, we Tamils don’t greet with “Namaste” but with “Vanakkam,” a smile, and a bow. In terms of food, generally we make sambar, a lentil stew with rice and vegetable salad with some pickles, and not Indian curry with flat wheat bread (i.e., chapati and naan, which are common in the northern parts of India). So, I hope these examples have convinced you that we are a little different.

But wait! I said my region is very different in culture when compared to the rest of India; but is Korean culture so very different from that of the Tamils? In Korea, people often bow when greeting and a common meal is rice with stew and some kimchi. Upon learning this, I couldn’t help but notice that Korean culture has some interesting similarities with Tamil culture. So, let’s explore how much alike we are.

Let’s begin from the very moment I set foot in the country at Incheon and called mom back home to tell her that I’d reached Korea safely! In Tamil, we call mom “amma” or, “ma” for short. I was surprised to see a small Korean kid using the same word “omma” (엄마, mom). Though a different word in a different language, they sound almost identical!

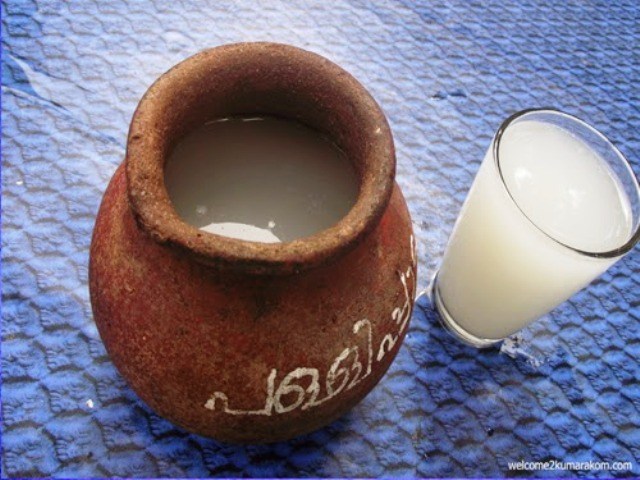

Now let’s talk about food. Generally, Indians eat a lot of spicy foods. We Tamils also eat spicy food, but not always. An everyday home-cooked meal consists of some boiled rice with a lentil stew (sambar) and a watery stew (rasam) with some vegetable salad and pickles. Pickles (oorugai) in Tamil Nadu are fermented or soaked in red pepper paste and some sesame oil, unlike in Western countries, where they’re soaked raw in vinegar. Additionally, a common breakfast in my region is rice soaked overnight in water and eaten the next morning, which is called pazaya soru, meaning “old rice.” Having just said that, now I’m hungry.

On one occasion, my friend, being vegetarian by choice, ordered some bap (밥, rice/a meal) at a Korean restaurant. To my surprise, the bap that my friend ordered for me was the same as the Indian platters I’m familiar with: a bowl of boiled rice, a stew with some spinach, some salad, and above all, kimchi, which is like pickles. Sounds yummy, right! I was surprised to see a food platter so similar to what’s served in my country thousands of kilometers away.

Though my Korean lab mates were shy to speak in English at the beginning, within a few days, we found great connections over shared interests in K-dramas and alcohol. In another instance, I along with my friends went to a bar to get some drinks. I wanted to try something specific to Korea, so my friends ordered soju (소주), makgeolli (막걸리), and jeon (전) with sides. Starting with the makgeolli, after a few rounds, I noticed the taste and texture were so similar to my region’s liquor, sundakanji.

Though I was a little too drunk then to explain the similarities to my friends, at least now I can mention it. One difference in drinking culture is that in Tamil Nadu, drinking is not as socially acceptable as in Korea. In fact, it’s quite a private affair, much like romantic relationships. Despite the social taboo, this doesn’t stop people in our region from having their own liquor recipes. We produce large amounts of rice, so naturally, we produce liquor also by fermenting it. Sound familiar? Yes, it’s much the same as the recipe for making makgeolli.

With drinks flowing, it was time to eat kimchi-jeon (김치전). My first thought was “Wow, this also tastes familiar. Doesn’t it taste like adai dosai?” Indeed it does. Adai dosai is a recipe made with lentil flour, oftentimes onion, and spinach toppings. It’s almost the same as yachae chon (야채 전). It doesn’t stop there, because we also have foods like yeot gangjeong (엿강정), namul (나물), and others. At the time, all I was thinking was whether I was still home or at my home away from home. Nothing creates a stronger bond with people than food and language. So, these have brought me closer to Korea and my Korean friends.

Let’s move on to festivals and celebrations. Indian calendars usually have a long list of national holidays, at least 20 days a year. But sadly, in Korea, we get only two main holidays: one is Chuseok (추석), the other Seolnal (설날). Within a few days of starting my PhD program, we had Chuseok vacation to celebrate the harvest season. “So, what’s the tradition?” I asked curiously to my friends. “We celebrate the year’s harvest by having a family gathering, saying thanks to the moon, and eating a variety of food together.” Then my friends asked me, “Do you have such a celebration?” Of course, ours is the same. In Tamil culture we celebrate Thai Pongal, but we celebrate in the month of January. On that day, we thank the sun for the good harvest, feed our cattle for helping in our farming, and go to our grandparents’ and other relatives’ homes to eat. On top of all this, we also share gift bags with rice, fruit, and homemade sweets and candies.

During that first Chuseok in Korea, I got a gift bag that, to my surprise, contained fruit and some Korean handmade sweets and candies. I really enjoyed them all, with my favorite being songpyeon (송편, rice cakes). We do have a similar food called kozhukattai, which is a savory coconut or other sweet filling stuffed inside rice cake that we serve on festive occasions.

So, having discussed in detail about food, let’s explore family and relationships, which are key parts of any culture. In Tamil Nadu, there are certain groups of people who call their husbands “anna” or “ayya” (meaning brother), which is much like the tradition of Korean ladies calling their husbands “oppa” (오빠). Having learned more about marriage and relationships, I learned that Korean ancient tradition is much like that of Tamils. In India, until recently, many men got married after only their fathers had met their potential brides. It is still considered a sign of respect for sons to ask their parents to meet their girlfriends. But now this culture is slowly changing, with love and dating followed by marriage becoming more common.

Once, during a casual chat with my friends, I learned that Korean tradition was also the same, but the culture has changed with the current generation. I further learned that Korean even has a term for it: seon (선). The ideology behind both customs is the same. Marriage is not just a matter of brides’ and grooms’ wants, but also their families’ interests. In addition, arranged marriages in both cultures were traditionally far more common. In my opinion, though it’s old-fashioned, these arrangements created strong family bonds. Other familial practices, like elder sons taking care of their parents after retirement or not drinking in front of parents, are also similar.

I learned these similarities based on events that happened around me over the past year and a half. It shows that though Korea and India are far apart geographically, we are so close with our culture and values! That’s the magical reason why I feel comfortable like I’m at home while staying here in Gwangju and fulfilling my dream of pursuing a PhD. I hope to explore Korea even more and learn its culture so I can share more in future articles. I would like to use this opportunity to thank my professor, lab mates, and all my other Korean friends who helped me and patiently explained their culture and practices. Also, I would like to thank the Gwangju News team for giving me this opportunity.

THE AUTHOR

Bala Krishnan Ganesan is a chemical engineering PhD student at Chonnam National University. His weekends are mostly spent playing cricket and cooking Indian food. When he’s not traveling around the country or busy with his studies, he loves hanging out with friends and, once in a while, writing about his experiences. Instagram: @nano_balki.