When the Rain Clouds Darkened: Apartheid South Africa

Written by Sashai Yhukutwana

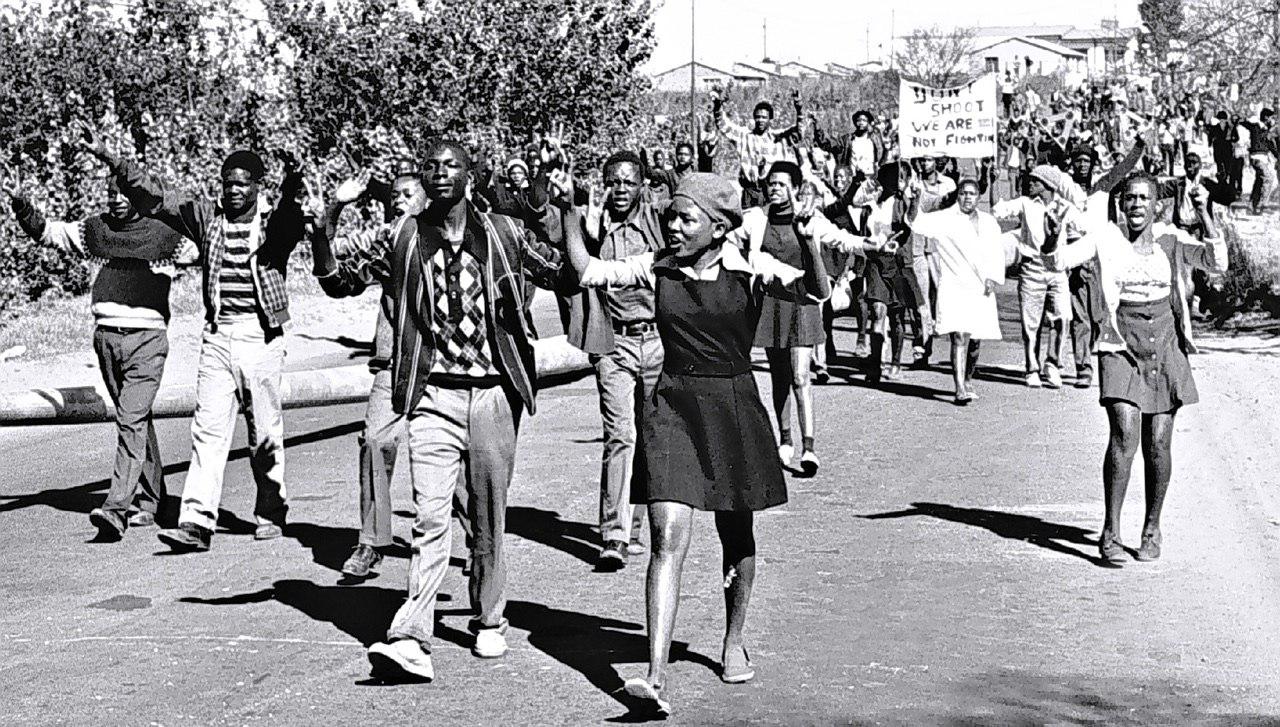

Photograph from Wikipedia

“Among modern countries where democracy is the favored system, the Athenian experiment eventually acquires a hallowed status. But more than 2000 years will pass, after the heyday of Athens, before anyone again regards with approval the dangerous idea of giving real power to the people.”

— Bamber Gascoigne [1]

Democracy is defined as having its power resting with the people, with political power being shared equally among individuals. The earliest system to have practiced this was the Athenian democracy of the fifth and sixth centuries B.C. In modern society, crucial tenets may include freedom of opinion and religion, the right to vote, separation of powers (between institutions), and human rights.

But can democracy be estimated to be a “dangerous idea” by those who rule? History is littered with records of dramatic action carried out by ordinary citizens to bring balance to power for a more tenable, dignified human existence.

It was not until the summer of 2017 that I became fully aware of the extent of events that shook Gwangju in May of 1980. I had learned of how protesting civilians were met with open gunfire. The cry for democracy was met with intolerant, indiscriminate martial law; the government wielded its authority to repress a rising tide of discontent while clinging to power. The citizens’ response? A love for country and a vision of a democratic future worth defending, worth fighting for, and worth dying for.

The Gwangju of the 1980s reminds me of what my home was in another time, where the citizens’ call for equality was seen as dangerous and undesirable – the all-too-familiar clamor to be heard, to be included, and to be allowed to live in dignity as an equal human being. Instead, the hope for an equal society was being crushed under a regime that sought to divide, conquer, and rule by fear and psychological warfare.

Apartheid (Dutch for “separateness”) was a system of political and social segregation practiced in South Africa from 1948 to the early 1990s. It employed white minority rule to divide the nation along racial, tribal, and class lines. The majority non-white population’s repression included a denial of equal human rights, political power, and capitalist gain. It also included a state of servility to the racially privileged minority, whose lives proceeded with relative ease, though also enshrouded in ignorance or fear of retaliation if they were to sympathize with the suffering majority.

But there were conscious objectors who rose to action. They are celebrated today for their courageous sacrifice and passion in events that were tragic and horrific – events that brought the nation’s distress and the government’s actions under international scrutiny but which culminated in a country that possesses an enviable constitution and Bill of Rights.

The Sharpeville Massacre, March 21, 1960 (now Human Rights Day)

The laws that governed black South Africans sought to degrade and strip away their dignity. One of these was the discriminatory Pass Law, which required black or non-white people to carry their identification papers (or pass books) at all times, as their movements were restricted.

In light of this law, the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) called on black South Africans to leave their pass books at home and assemble at local police stations to demand that the police arrest them for not carrying their passes. The PAC’s desire was for black people’s total independence and freedom, which members of the organization believed could come to pass by 1963. They thought, if thousands were arrested, the country’s jails would be filled and the economy would come to a standstill. By midday of March 21, nearly 5,000 residents gathered at the police station in Sharpeville, a township just outside Johannesburg. This was planned as a peaceful campaign, yet they were met by approximately 300 heavily armed police.

There was no provocation, but a police officer panicked and, without any warning shots, opened fire on the unarmed crowd. His colleagues followed suit. The firing lasted for approximately two minutes. Those who were shot were wounded mostly in their backs as they were fleeing. Sixty-nine people died and 180 were seriously wounded.

“The shooting at Sharpeville sent shockwaves around the country and the world. The African National Congress (ANC) president, Chief Albert Luthuli, called on people to burn their passes and declared a day of mourning. He also called for a nationwide one-day “stay at home.” After this, the government passed the Unlawful Organisations Act on April 7, 1960, and banned the ANC and the PAC.”[2]

Soweto Youth Uprising, June 16, 1976 (now Youth Day)

This uprising brought in new energy and impetus for the liberation struggle against apartheid, which had weakened after the ANC and PAC movement leaders were exiled, thus seriously affecting the South African political landscape. Thousands of students were mobilized on that day in Soweto, South Africa’s largest township, to protest the use of the minority language, Afrikaans, for classes and for examinations. This, on top of an already inferior education system for black South Africans, compelled the students to march and peacefully demonstrate against the government’s mandate. The brutality of the regime was most vividly exposed on this day as heavily armed forces fired teargas and later live ammunition at the students. The blood of those who fell only sought to water the seeds of revolt, causing an uprising against the government.

“While the uprising began in Soweto, it spread across the country and carried on until the following year. The aftermath of the events of June 16, 1976, had dire consequences for the apartheid government. Images of the police firing on peacefully demonstrating students led an international revulsion against South Africa as its brutality was exposed.”[3]

Maybe democracy is a dangerous idea. It has called governments to arms, even against the unarmed. May we never forget the sacrifices that cost so dearly but gave us the freedoms and peace we enjoy today.

References

[1] Gascoigne, B. (From 2001, ongoing). History of democracy. Retrieved from the World History website: http://www.historyworld.net/wrldhis/PlainTextHistories.aspgroupid=2632&HistoryID=ac42>rack=pthc

[2] South African History Online. (2000-2017). Sharpeville. Retrieved from http://www.sahistory.org.za/jquery_ajax_load/get/article/sharpeville

[3] South African History Online. (2000-2017). The June 16 Soweto Youth Uprising. Retrieved from http://www.sahistory.org.za/topic/june-16-soweto-youth-uprising

THE AUTHOR

Sashai Yhukutwana is an English teacher in Gwangju. She likes taking advantage of open evenings to read, nap, do Bible studies, cook, and sometimes have a nice chat with a friend over a hot drink or go for a weekly sweat at Zumba. Her students know her as a basketball player, coworkers think she is a fashionista, and yet Sashai truly likes nothing more than seeing others shine their light bright for their absolute pleasure, and the benefit of all.