A Look Back at Taiwan’s 1979 Kaohsiung Incident

Written by Stephen White

Photographs from Wikipedia

The Kaohsiung Incident of 1979 was a watershed in Taiwan’s political and social history. At the time, it was barely noticed internationally, but it has since been recognized as one of the key events that helped the island transition to democracy. Perhaps most importantly, it galvanized both local and overseas Taiwanese into political action and awareness.

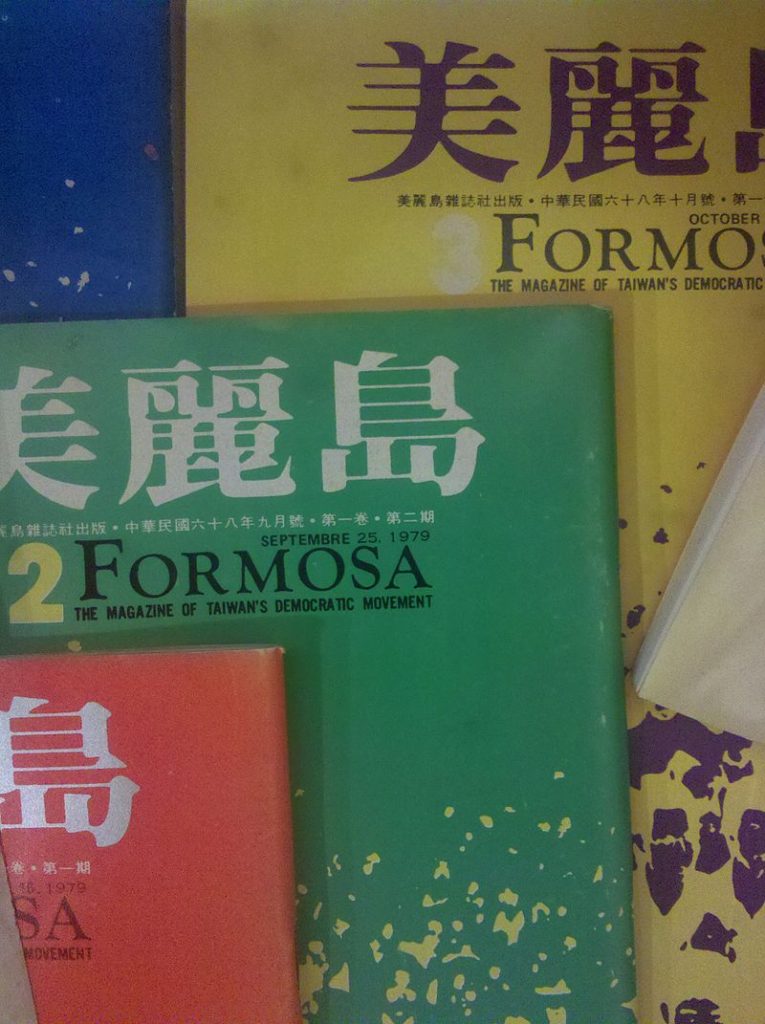

The incident started out as the first major Human Rights Day celebration of Taiwan. Until that year, the authorities had never allowed any public expression of discontent, but in the summer of 1979, they relented, at which time two opposition magazines were established: Formosa Magazine and The Eighties. Formosa Magazine quickly became the rallying point for the budding democratic movement and a means to resist the government.

During the fall of 1979, Formosa Magazine had become increasingly outspoken and the upcoming Human Rights Day was an obvious opportunity to further express its views on the lack of democracy and human rights in Taiwan. Before the event even started, the atmosphere had become tense because of increasingly violent attacks by right-wing extremists on offices of the magazine and homes of leading staff members.

The magazine’s Kaohsiung Center had applied several times for a permit to hold a human rights forum at an indoor stadium, but all the requests were denied. In response, it was decided to hold the demonstration at the Kaohsiung headquarters instead. Unofficial estimates said the demonstration involved between 10,000 and 30,000 people, and it was always intended as a peaceful call for human rights. However, several hours before the event had even started, the military police, the army, and the police had already taken up positions.

When the event took place during the evening, the military police marched forward and closed in on the demonstrators, and then they retreated back to their original position. This tactic was repeated two or more times with the purpose of causing panic and fear in the crowd. Despite calls for calm by the protest leaders, the crowd of protestors was eventually goaded into retaliating. There are several reports that pro-government instigators were also responsible for inciting violence between the two groups. Regardless of how exactly it started, the police encircled the crowd and started using teargas and violent physical force.

Newspaper reports right after the event stated that in the ensuing confrontations, more than 90 civilians and 40 policemen were injured. However, the authorities produced figures of 182 policemen and one civilian injured. Although most injuries were relatively minor, the authorities played up the injuries on the police side, sending high officials and actresses to the hospitals to comfort the injured policemen to create a publicity stunt.

More seriously, three days later, the authorities used the incident as an excuse to arrest virtually all well-known opposition leaders. They were held incommunicado for two months, during which time reports of severe ill-treatment filtered out of the prisons.

The arrested persons were subsequently tried in three separate groups: In March–April 1980, the eight most prominent leaders (the “Kaohsiung Eight”) were tried in military court and were sentenced to terms ranging from 12 years to life imprisonment; in April–May 1980, a second group of 33 persons (the “Kaohsiung 33”), who had taken part in the Human Rights Day gathering, was tried in civil court and sentenced to terms ranging from two to six years.

A third group of ten persons associated with the Presbyterian Church was accused of helping the main organizer of the demonstration, Mr. Shih Ming-teh, when he was in hiding because he feared torture and immediate execution. Most prominent among this group was Dr. Kao, the general-secretary of the Presbyterian Church. Dr. Kao was sentenced to seven years imprisonment and the others received lesser sentences.

The importance of the incident is the fact that it totally changed the political landscape of Taiwan. Taiwanese generally became more politically aware, and the public was forced to take a side in the incident. The movement that grew out of the incident subsequently formed the foundation for the present-day democratic opposition, the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP), and its overseas support network of Taiwanese organizations in North America and Europe. Virtually all leading members of today’s democratic opposition had a role in the event, either as defendants or as defense lawyers.

Looking at the history of this event, it’s not hard to draw parallels between Taiwan’s Kaohsiung Incident and Gwangju’s May 18 Democratic Uprising. To paraphrase Noam Chomsky: The way things change is by lots of people working [and suffering]. They’re working to build up the basis for popular movements that are going to make changes. That’s the way everything has always happened in history, whether it was the end of slavery or a democratic revolution, anything you want, you name it, that’s the way it worked.

The Author

Stephen is a South African who has been living and working in Korea for the past six years. He’s lived all over Korea, from the smallest towns in Jeollanam-do to the center of Seoul. He’s passionate about education, history, and language.