Jeong Beom-sik’s Ghost Movies

Whisperings and Topology of Anxiety

Written by Régis Olry.

Korean director and writer Jeong Beom-sik’s filmography is quite diversified, including the action thriller The Man from Nowhere (Ajeossi, 아저씨), the historical saga Forbidden Dream (Cheonmun: Haneul-e Mutneunda, 천문: 하늘에 묻는다), the comedy Working Girl (Weokinggul, 워킹걸), the short movie The Escape (Tal-chool, 탈출), which is a segment of the 2013 omnibus film Horror Stories 2 (Mooseowon Iyagi 2, 무서운 이야기 2). But two of his masterpieces will today hold our attention: 2007’s Epitaph (Gidam, 기담) on the one hand, and 2018’s Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum (Gonjiam, 곤지암) on the other. Both movies have two interesting common features: They take place in a hospital and make us hear (and see) scary, whispering ghosts.

Epitaph takes place in Ansaeng Hospital (Figure 1) in the early 1940s, while Korea was still under Japanese rule. After a car crash, the young Asako (played by Ko Joo-yeon) is sent to this hospital, but her mother, Park Ji-a, unfortunately did not survive. She becomes a ghost, comes back to the hospital to whisper to her frightened daughter that she was not responsible for causing the accident and that she should stop feeling guilty (Figure 3).

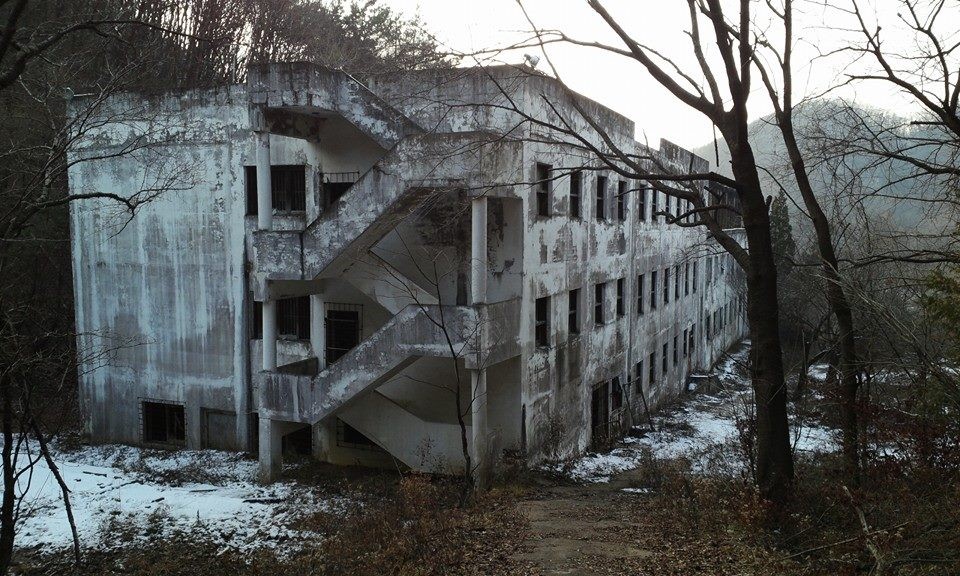

Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum belongs to the so-called found-footage movies1. It is set in the now-demolished Gonjiam Psychiatric Hospital (Figure 1, cover photo), the story of which “reads like a textbook plot or a horror film2.” A group of six youngsters decides to do a live broadcast of this supposedly haunted spot by night, but it is not long before scary supernatural phenomena occur. While running away from the abandoned building, two girls from the team, Ji-hyun (Park Ji-hyun) and Charlotte (Moon Ye-won), get lost in the forest surrounding it. Suddenly, Ji-hyun starts whispering loud, incomprehensible words, possessed by a ghost of the asylum (Figure 4).

Obviously, Ji-hyun’s and Asako’s mothers’ whisperings are very similar, to the point of seeing them as director Jeong Beom-sik’s mark.

Whisperings

In 2019, Canadian researcher Sandra Huber raised a very interesting question: “What do the dead have to say and how do we listen3?” In Korean (and actually Northeast Asian) folklore, ghosts may come forward for many reasons: to express reproach, to ask friends and relatives for more explanations, to confess a secret never disclosed when alive or, at worst, to get even with someone. The latter can be found in the legend of the young virgin named Arang: “I am the spirit of Arang lingering in this world because my revenge is not yet accomplished4.”

But how do ghosts manage to communicate with the living? They may appear in dreams, write letters or even poems5, use electromagnetic fields (see Yoo Sun-dong’s 2019 0.0MHz), or other technological media but, according to Konaka Chiaki’s theory6, Japanese ghosts should not speak. In his interesting study of Asian ghost movies, David Kalat recognises this as a feature of Korean ghosts as well when he writes that Choi Ik-hwan’s 2005 Voice (Yeogoedam 4: Moksori, 여고괴담 4: 목소리) “establishes a repeating pattern that seems certain to produce an unending cycle of voiceless ghosts.7” This may explain why, whether it is to scare or to call for help, ghosts can express themselves only by whispering8,9. And if director Park Ki-hyung’s 1998 metaphor that corridors are supposed to whisper (Whispering Corridors, Yeogogoedam, 여고괴담), it may be caused, like in Shadows in the Palace (Gungnyeo, 궁녀), by ghosts which “prowl inside the wall10.”

Topology of Anxiety11

Many ghost movies “rely heavily on the background setting to advance the horror narrative12.” Even though the leading role of Thai director Sopon Sukdapisit’s 2017 movie The Promise should have been the young girl who committed suicide, it is actually played by the building where this drama took place, the famous, impressive, and supposedly haunted Bangkok Unique Sathorn Tower13. But among all types of buildings acknowledged as haunted spots, hospitals are without a doubt lying first. Why?

Of course, hospitals are places of birth and recovery. But they also inspire people with fear: fear of a bad diagnosis, fear of suffering, fear of losing one’s mind, and finally, the fear of the so-called “malemort14” or “bad death15”, a universal concept in Asian folklore. Now, as untimely death is the best way to become a ghost, it is then not a surprise to hear that many hospitals are haunted, especially if they are about to close under strange circumstances (see Kong Su-chang’s 2006 series Coma, 코마), or if they have been abandoned for a long time, such as with the Old Changi Hospital in Singapore16 (the setting of Andrew Lau’s 2010 movie Haunted Changi). But the most frightening hospitals are, of course, the abandoned psychiatric asylums, which combine disrepair, death, and madness. Hence the success of Gonjiam: Haunted Asylum.

Footnotes

1 Ancuta, Katarzyna. (2015). Lost and found: The found footage phenomenon and Southeast Asian supernatural horror film. Plaridel, 12(2), 149–177.

2 Yoon, Min-sik. (2018, March 21). Navigating the dark corners of a haunted asylum. “Gonjiam: Haunted asylum” is typical found-footage horror film, but tells a legitimately scary story. The Korean Herald.

3 Huber, Sandra. (2019). Villains, ghosts, and roses, or, how to speak with the dead? Open Cultural Studies, 3, 15–25.

4 Faurot, Jeannette. (1995). Asian-Pacific folktales and legends (p. 174). Touchstone.

5 Marchand, Sandrine. (2017). Poèmes de femmes, poèmes de revenants sous la dynastie Qing (1644–1911). In Fantômes dans l’Extrême-Orient d’hier et d’aujourd’hui. Vol. 1. Presses de l’Inalco. http://books.openedition.org/presseinalco/1720

6 du Mesnildot, Stéphane. (2011). Fantômes du cinéma japonais (pp. 56–58). Rouge Profond.

7 Kalat, David. (2007). J-horror: The definitive guide to The Ring, The Grudge, and beyond (p. 211). Vertical.

8 Murphy, Fiona. (2018). The whisperings of ghosts: Loss, longing, and the return in stolen generations stories. The Australian Journal of Anthropology, 29(3), 332–347.

9 Knee, Adam. (2007). The transnational whisperings of contemporary Asian horror. Journal of Communications Art (Thailand), 25(4).

10 Hwang, Yun-mi. (2013) Heritage of horrors: Reclaiming the female ghost in Shadows in the Palace. In A. Peirse & D. Martin (Eds.), Korean horror cinema (p. 83). Edinburgh University Press.

11 In this paper, we will not draw on the Lacanian distinction between anxiety and fear.

12 Hwang, Yun-mi. (2013). Op. cit., p. 76.

13 Pohl, Lucas. (2020). Object-disoriented geographies: The Ghost Tower of Bangkok and the topology of anxiety. Cultural Geographies, 27, 71–74.

14 Baptandier, Brigitte (Ed.). (2001). De la malemort en quelques pays d’Asie. Karthala.

15 Formoso, Bernard. (1998). Bad death and malevolent spirits among the Tai peoples. Anthropos, 93, 3–17.

16 Zakaria, Falzah. (2019, November). Old Changi Hospital. Singapore Infopedia.

THE AUTHOR

Régis Olry, M.D. (France), is professor of anatomy at the University of Quebec at Trois-Rivieres (Canada). In the early 1990s, he worked in Germany with Gunther von Hagens, the inventor of plastination and the BodyWorld exhibitions. He currently studies the concept of Asian ghosts in collaboration with his wife who is a painter. (see www.gedupont.com)